El Anatsui, who is this year’s artist commissioned to make work for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, is best known for his metallic sculptures constructed from thousands of recycled bottle tops—sourced from local recycling stations—joined together with copper wire. These often massive cascading works fuse local aesthetic traditions with the global history of abstraction as well as political, social and environmental concerns around consumption, national identity and trade.

Born in Anyako, Ghana, in 1944, Anatsui has spent most of his career in Nigeria as an artist and teacher, serving for more than four decades as professor of sculpture at the University of Nigeria in Nsukka. As well as the bottle top works he has been making since the late 1990s, Anatsui has developed a highly experimental approach to sculpture, embracing wood, ceramics and found objects. In 2015 he was awarded the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement at the 56th Venice Biennale and his 2019 solo show at the Haus der Kunst in Munich was the last to be curated by the late Okwui Enwezor, who was one of Anatsui’s greatest champions. To coincide with Behind the Red Moon, his Hyundai Commission for Tate, Anatsui is also showing new works using both wood and bottle tops at the October Gallery in London.

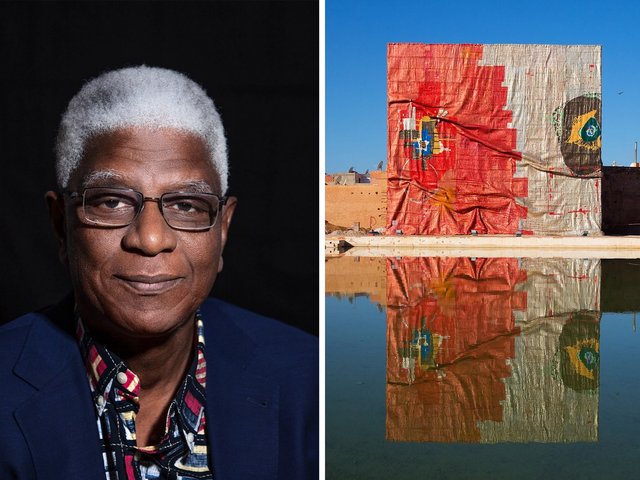

El Anatsui in front of his work in Tate Modern Photo: © Tate; Lucy Green

The Art Newspaper: How did you approach making work for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall?

El Anatsui: I started with the name Tate, which is not a strange name to me. I grew up in the colonial Gold Coast and until the 1960s, when another brand of sugar was introduced, the sugar that we used was Tate & Lyle sugar. So I started thinking about things which have a resonance or links to the transatlantic slave trade. Tate did not take part in the transatlantic slave trade but it benefited from its aftermath, and so I wanted to do something with this. Ghana has the largest concentration of slave castles—close to 40 or so—on its short coast. And when I visited one of the most iconic castles at Cape Coast, what struck me was that there were dungeons underground and on top of them a chapel, in a kind of heaven-and-hell combination. I wanted to recreate the portion of that castle, which showed this configuration, in a simulacrum of sugar. But the Turbine [Hall] was too small for this, so we had to drop that idea. Then I decided that with the bottle caps I’m already working with something that has links with transatlantic slave trade and sugar. And these caps are also such a versatile medium that can fit into any space, whatever the size. So that’s what I’m working with.

Can you talk a little about your early search for an artistic voice at a time of tumultuous change in Africa?

I grew up in a mission house where there wasn’t much contact with the outside world: life was between the classroom and the church. Through school and then to university everything we were doing was western, and especially in the fine art department of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, where it was all western art history. So at the beginning I was sequestered from getting to know my culture, and at the end of university I felt that there was something missing, I didn’t believe the idea that art was something that was only done in the West.

What did you do to rectify this?

I started going to the National Cultural Centre of Ghana in Kumasi, where the university was located. Here musicians, graphic artists, makers of textiles, printers, all these creative workers gathered in one place and I had my first encounter with something that was African, something that was Ghanaian, something that was indigenous. I discovered the system of signs called Adinkra, which uses graphic symbols to convey meanings and ideas without using the human form. This was my first introduction to abstract art: after so many years of life studies and life modelling, I was looking at a body of work which was not trying to express the world visually but through the mind. It opened up a new world.

Anatsui's Behind the Red Moon in the Turbine Hall Photo © Tate (Lucy Green)

How did this new abstract language manifest itself in your work?

I discovered these round wooden trays that were used by market traders to display their wares, which I thought would make a very interesting support for the Adinkra signs that I’d been trying to master. I found the carvers who produced these trays and I got them to design different sizes and shapes. Then I’d put the Adinkra signs in the middle of the trays and on the border I’d create patterns of forms that would help to elucidate the meaning of whatever symbol was in the middle. The process I used was a low-tech one of putting an iron rod in the fire and making a brand in the wood. Everything that I used was available and sustainable.

A desire to work with what is closely available has remained with you to this day.

Yes, that was a crucial shift that has carried me along so far. Working with things that are immediately available and accessible means whatever you’re doing relates to your environment, to the people and the culture. That was my way of trying to put myself into the culture that I’ve been denied from school. When I first exhibited the works on trays, they resonated with everybody because they saw them every time they went to the market—seeing them in a new context was exciting to them.

Over the past decades you’ve used a wide range of materials. But whether it’s old wooden mortars, metal cassava graters, the lids of evaporated milk cans or the aluminium bottle tops for which you are now best known, you’ve predominantly chosen to work with objects that have had a previous use before being given a new purpose in your art. Why is this past history so important?

When something has been used, there is a certain charge, a certain energy, that has to do with the people who have touched it and used it and sometimes abused it. This helps to direct what one is doing, and also to root what one is doing in the environment and the culture.

A detail of Anatsui’s AG + BA (2014). The colourful bottle tops used in his signature works have layers of environmental and socio-political meaning Photo: © Jonathan Greet; © El Anatsui; Courtesy of the Artist and October Gallery

You’ve been working with metal bottle caps for more than 20 years, what is so special about them?

From the beginning I was aiming at a form that doesn’t have a description. Like a sheet of cloth, it is versatile enough to do so many things [with] and be described in many different ways. But I think I misled people because I gave the first two pieces of this work the titles Man’s Cloth and Woman’s Cloth, and the colour scheme of these bottle cap works replicated the colours of Kente fabric. So it was difficult to take people’s mind away from Kente and textiles, but I was always thinking about sculpture, not about textiles.

Yet your bottle cap works can also be very painterly: sometimes monochrome, sometimes densely patterned, sometimes translucent like watercolours, and with colour playing an increasingly central part.

To start with I was using the inside, which is just the silver of the metal (with the colour on the outside). It was like me starting off as a sculptor not paying any attention to colour, and then all of a sudden finding something I’d been ignoring: the colours of their caps. So I had to start thinking like a painter as well, grappling with how to match colours and what to do with colour to carry some meaning or message. In the end I’m doing a combination of sculpture and painting. Because I don’t show them like a painter would show a work, stretched on canvas, I give them three-dimensional folds and forms as well. So you have form and colour all coming in.

And also rich layers of content. Every one of these thousands of elements recalls a bottle drunk, and there’s also the environmentally pertinent fact that you are repurposing these discarded elements of commerce and consumption into art. Then there are also the socio-political-historical resonances in these expanses of bottle tops.

Yes, there are aspects of the bottle tops that I don’t think anybody has paid any attention to. The names of the drink brands are all on the caps, and doing a study of those names alone gives a glimpse of the sociology and current political and historical issues. For example, the drink called Black Gold resonates with the fact that drinks were exchanged for slaves that were then transported to America. Or there’s a drink called Ecomog, which is the same name as the military force sent by the Ecowas [Economic Community of West African States] during the war in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

When your bottle cap works are installed, you usually leave it up to the curators to decide how they will be folded, draped and hung. Why do you let other people interpret your work? Is it like playing a musical score?

In an unconscious way, my works are about the freedom for people to do things. I have a hidden aim of waking up the artist in everybody and if you give people the challenge and say, ‘here is something folded and you can open it and do whatever you want to do’, it wakes up the artist in them and frees the imagination. Freedom is so very important, it can ameliorate so many things.

Kindred Viewpoints, a hanging made with aluminium bottle caps and copper wire, which Anatsui created for the 2016 Marrakech Biennale Photo: Jens Martin; courtesy of Marrakech Biennale 6

Biography

Born: 1944 Anyako, Ghana

Lives and works: Nsukka, Nigeria and Tema, Ghana

Education: 1965-68 College of Art, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

Key shows: 2003 Mostyn, Wales; 2006 Mori Art Museum, Tokyo; 2007 Venice Biennale and Palazzo Fortuny, Venice; 2010 Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, 2013 Royal Academy of Arts, London; 2016 Marrakech Biennale 6; 2019 Ghana pavilion, Venice Biennale and Haus der Kunst, Munich; 2020 Kunstmuseum Bern

Represented by: October Gallery, Jack Shainman Gallery, Goodman Gallery and Sakshi Gallery

• Hyundai Commission: El Anatsui: Behind the Red Moon, Tate Modern, London, 10 October-14 April 2024

• El Anatsui: TimeSpace, October Gallery, London, 11 October-13 January 2024