Dana Claxton received this year’s Audain Prize, one of Canada’s most coveted arts awards, during a ceremony on Monday (25 September). The C$100,000 ($74,000) cash prize honouring distinguished British Columbia-based artists was announced at a luncheon at the Fairmont Hotel Vancouver.

When Reid Shier, executive director of the Polygon Gallery in North Vancouver, awarded the prize on behalf of the jury, he praised Claxton’s “multilayered” practice. He described the photography in her series and book Paris, June Fourth, Fifth, & Sixth, Two Thousand & Six as being “as much [Jack] Kerouac as [Eugène] Atget”—and spoke of her “landmark” work as a First Nations woman—a group who are “systemically denied a place in the art world.”

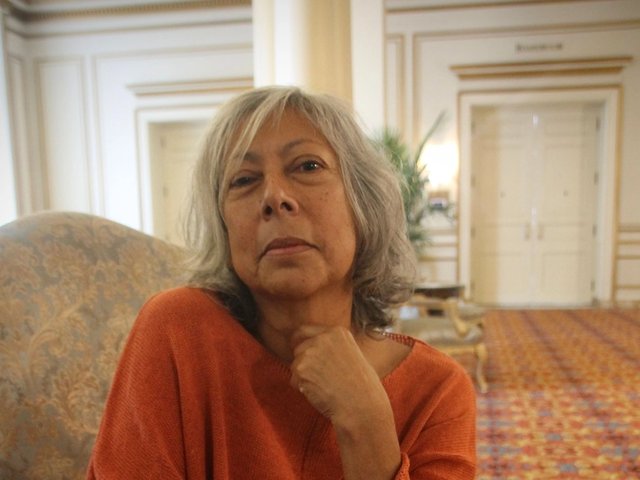

Claxton, a Vancouver-based artist whose work spans film, photography, video and multi-channel installation, is a member of the Wood Mountain Lakota First Nations located in Southwest Saskatchewan. Her practice investigates Indigenous beauty, the body, the socio-political and the spiritual and has been widely exhibited across Canada and internationally. She is also a professor at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and head of its department of art history, visual art and theory.

Dana Claxton, The Mustang Suite: Daddy’s Gotta New Ride, 2008 Courtesy the artist

In a statement, Claxton noted the Audain Prize’s history of acknowledging First Nations artists, saying, “It is a great honour to be included with this group, which includes esteemed BC artists like Susan Point, Jim Hart and Robert Davidson, all who have won the Audain Prize.” In a video played at the event, she spoke of the ongoing “criminalisation of Native culture”, saying that her work was ultimately about “not dehumanising people”.

A past recipient of the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts in 2020, she had a solo survey exhibition, Fringing the Cube, at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 2018 and her series Headdress (2018-19) had its debut at the inaugural Toronto Biennial of Art in 2019.

“Besides having an outstanding international reputation, Ms. Claxton has had a considerable influence on younger artists and her UBC art students,” says Michael Audain, the chairman of the Audain Foundation, who founded the award in 2004.

Dana Claxton, Buffalo Bone China, performance at AKA artist-run centre, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, 1997. Courtesy of AKA and the artist.

Claxton is known for her video work like 1997’s Buffalo Bone China, evoking the animals’ slaughter for a European luxury item via mesmeric pixelated loops of phantom buffalo running through the plains, a white hunter shooting them and a native man alternately crying in pain and caressing fine bone china. This work, like many others by the artist, collapses the historical into the contemporary.

Performance art is also a pillar of her work, like 2011’s The Elsewhere—an attempt to “Indianise space” through the use of gesture, music, and natural and man-made objects—which incorporates elements of Lakota ceremony. Her photographic work, like 2008’s Mustang Suite, employs ironic humour to defy stereotyped imagery of First Nations. As Shier put it, her work performs a “critical reversal” of “who might be looking at whom”.

In an interview with The Art Newspaper, Claxton cites a variety of influences including the multi-disciplinary artist Paul Wong and her experience in the early 1990s at Vancouver’s Video Inn media arts centre, to the Vancouver School and photo-conceptualists like Jeff Wall, First Nations filmmaker Loretta Todd, as well as her own family and Lakota traditions.

Dana Claxton, Headdress – Dana, 2019 Courtesy the artist

Vancouver’s simultaneous cultures of “artist-run centres and artist-as-curator” she says, as well as its “large indigenous contingency of cultural producers and image makers”, were formative influences. “It feels wonderful to win this award,” she adds. “It’s an honour, a privilege and a real blessing.”

Past winners of the Audain Prize have included the photo-conceptualist Ian Wallace, in 2022; and sculptor James Hart, the hereditary chief of the Eagle Clan of the Haida Nation, in 2021.