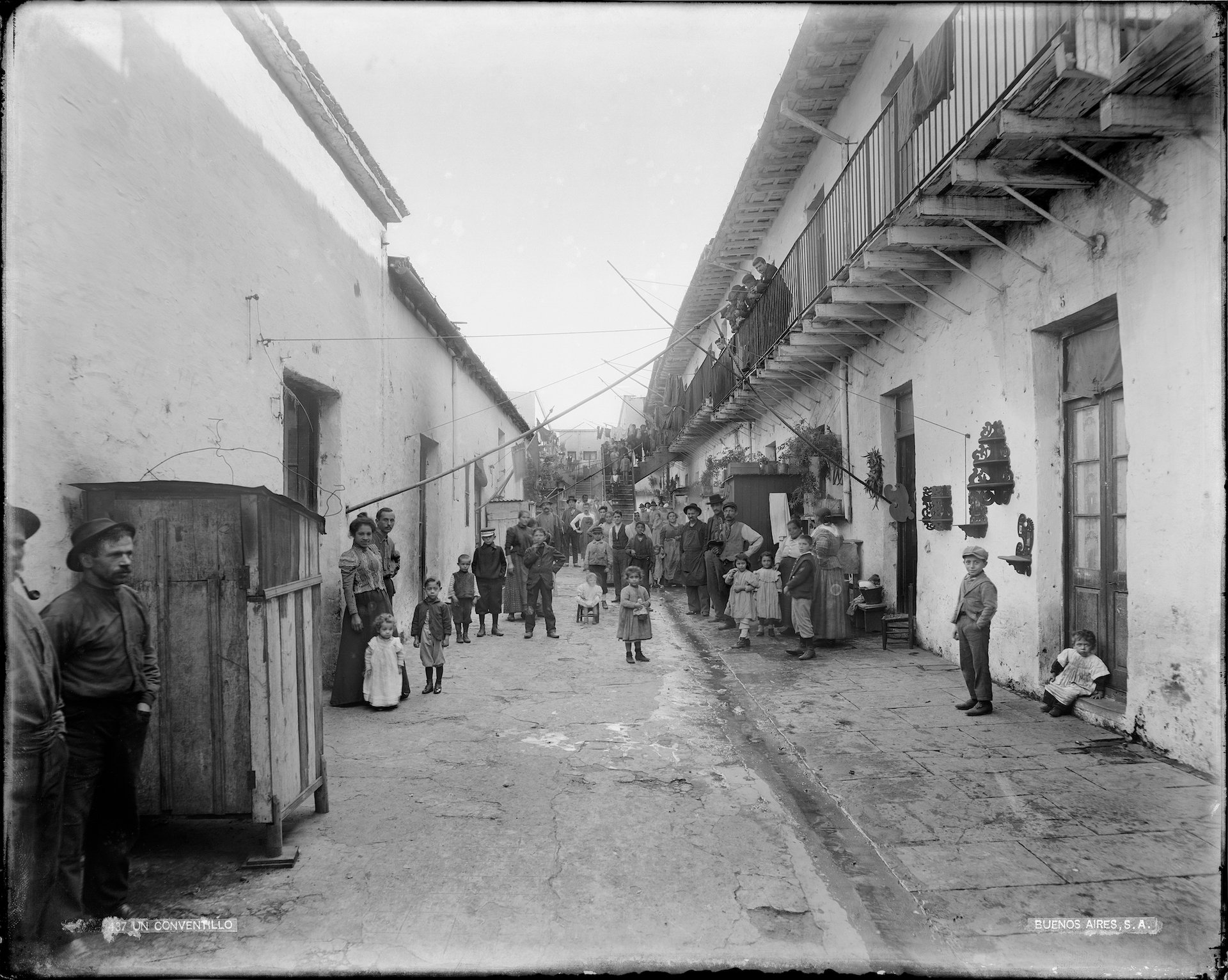

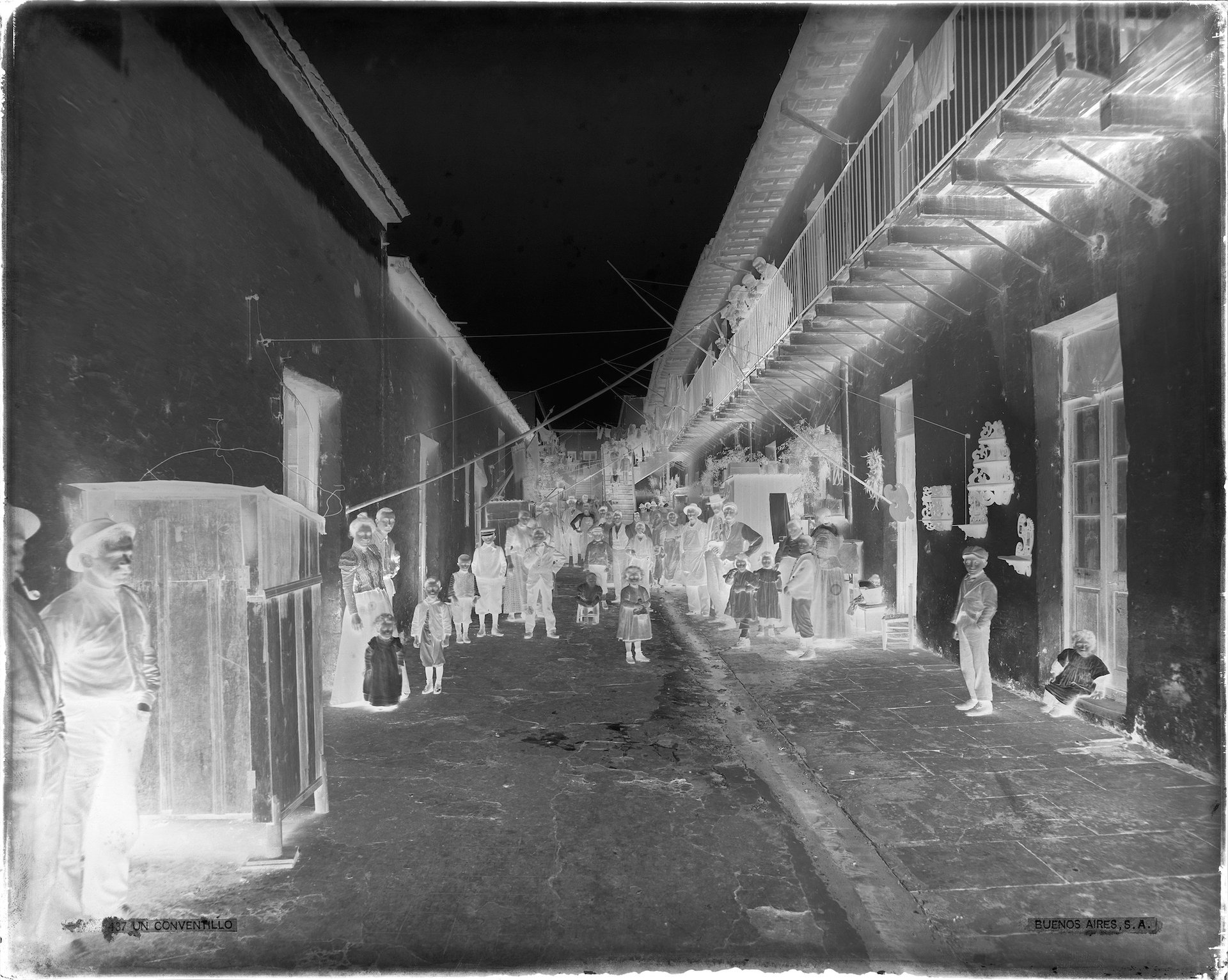

The dramatic black-and-white photo mural El Conventillo, which refers to a type of tenement popular in Argentina, is cinematic in its scope. The main figures, near the front, include young boys dragging on their cigarettes with a sort of premature swagger. In the background, you can make out men hanging over a balcony in front of a clothesline and a woman nearby scowling.

The mural captures the immediate effects of poverty—on faces, clothes, housing, crowding—in a Buenos Aires tenement around 1902, and is currently being shown in the city’s working-class neighbourhood of La Boca, so that immigrants today can come face to face with those from more than 100 years ago. It is based on an 8in-by-10in glass-plate negative by Harry Grant (H.G.) Olds, who was an immigrant himself: an American photographer who documented Argentina during a destabilising period of great industrialisation and immigration—what might be considered the country’s last stage of modernisation.

H.G. Olds, 437. Un Conventillo. Buenos Aires, S. A., around 1902 CIFHA Foundation

“It’s amazing to think that the most iconic images of Argentina in the beginning of 20th century were made by an experimental artist who grew up in 19th-century America. And Olds made many of these images without knowing how to speak Spanish,” says Alfredo Srur, a curator of the new Olds exhibition El extranjero (The foreigner, until 17 December) at the CIFHA (Centro de Investigación Fotográfico Histórico Argentino) gallery in Buenos Aires. Srur compares Olds to Richard Avedon or August Sander when it comes to the power of his portraiture.

With the help of small grants, CIFHA—and often Srur singlehandedly—has for the past ten years been cleaning, conserving, organising, exhibiting and working to publish the archive of H.G. Olds. The current exhibition, featuring the mural, follows one that took place at FoLa (Fototeca Latinoamericana) in 2017. Srur has produced a YouTube video in English documenting Olds’s journey as a photographer—and his own as Olds’s advocate. Next up, CIFHA is developing a book featuring about 150 images of Argentina by Olds, some earlier work and excerpts from his writing, with a target publication date of 2024. This is all designed to put Olds on the map—in the US and Argentina.

Buckeye State beginnings

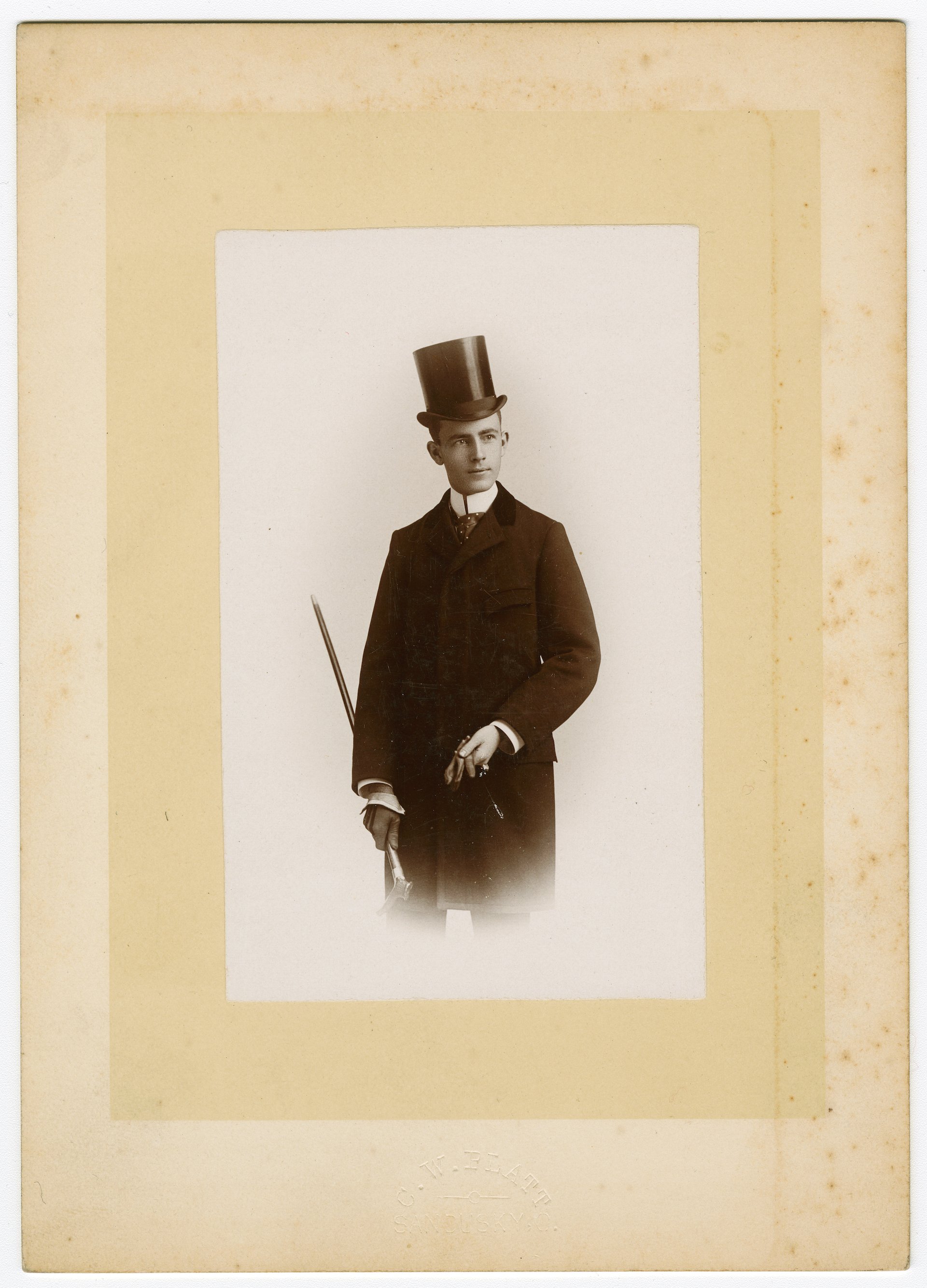

Born in Sandusky, Ohio, in 1868, Olds studied tintype-making early on at Willard A. Bishop’s photography studio there and opened his own shop in the area with another photographer when he was still in his 20s. But by the time he was 30, the economy was weak, their business was struggling and he felt the locals did not appreciate his “innovative ideas in photographic art”. He sold his share in the studio and, at the urging of an uncle in Buenos Aires, decided to take a job at a photography studio in Chile.

Portrait of Harry Grant Olds by photographer W. A. Bishop at C. W. Platt Gallery, Sandusky, Ohio, around 1888 CIFHA Foundation

In 1899, he took the steamer Buffon to Valparaiso, Chile, stopping in several Brazilian ports, Montevideo and Buenos Aires along the way. Everywhere he went, he took pictures with his large-format camera: streetcars, shipyards, landscapes and portraits. After working for a time in Chile, Olds settled in Argentina, and his girlfriend, Rebecca Jane Rank, followed. They married and stayed in the country until he died in 1943. A few years later, she moved to Florida with a trunk of his correspondence, early tintypes and the photographs he had made on that South American journey.

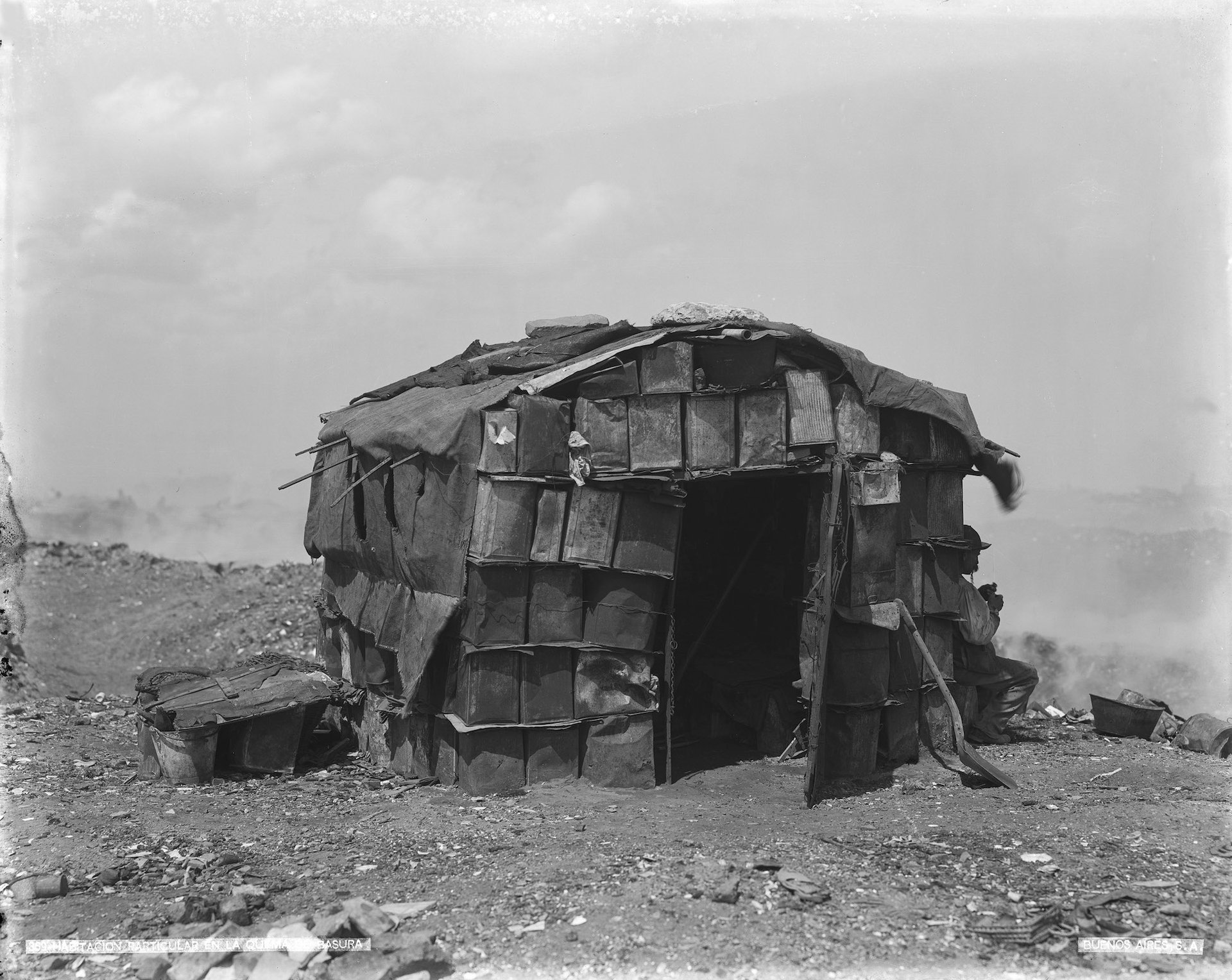

Srur, a former photojournalist and photography educator, first encountered Olds’s archive in person about ten years ago. Before that, he had only seen one book of his works. But he was drawn to what he found—like Olds’s image of a shantytown structure in Buenos Aires made from empty fuel cans, which he set as his screensaver. “When you first see the image, you don’t even notice the person rolling a cigarette, I think, in one of the worst places in the city of Buenos Aires. You can almost confuse him with the smoke,” Srur says.

H.G. Olds, 369. Habitación particular en la quema de basura. Buenos Aires, S.A., around 1901 CIFHA Foundation

Lost trove rediscovered

When Srur’s interest in ambrotypes led him in 2013 to a vintage photography seller, he was stunned to learn of an elderly colleague, Mateo Giordano, who had received—through a connection to Olds’s assistant—bags of the photographer’s original glass-plate and nitrate negatives from his work in Argentina. Srur was equally shocked when, at their first meeting at a gas station's coffee shop, Giordano brought out some of the glass plates and set them on the table next to the coffee and pastries.

The glass plates were in bad shape, dusty and mouldy from the humidity of Giordano’s apartment. But they were intact. And after six months of negotiation, Srur bought that work (more than 1,000 negatives) and went to Ohio to see Rank’s trunk, which belonged to stereoscopic-photography expert John Waldsmith.

H.G. Olds, 437. Un Conventillo. Buenos Aires, S. A., around 1902. Gelatin silver bromide glass plate negative, 8in by 10in CIFHA Foundation

Waldsmith gave the trunk to Srur, who with these two archives went on to found the non-profit foundation CIFHA to preserve Olds’s legacy. He started by cleaning the plates using conservation techniques he had taught himself via the internet. Now, Srur calls CIFHA, where he is executive director, “the biggest private collection preserving and disseminating Argentine photography—historical and contemporary—in our country”, ranging from daguerreotypes to his own work.

CIFHA has a full-time staff of five, but it still has the feel of a one-man operation in that Srur drives a lot of the work they do. And he is aware that his own quest to make sure Olds does not remain in the margins—like the man you can hardly see through the smoke—has taken on an obsessive character. Or, as he says at the end of his YouTube video, “I make Olds live on, as I would like to live forever.”

- H.G. Olds: El extranjero, until 17 December, Centro de Investigación Fotográfico Histórico Argentino, Buenos Aires