For decades, a mesmerising shrine of Tibetan Buddhist artefacts has been tucked away in a private home on New York’s Upper East Side. This month, the contents of the shrine, more than 200 artefacts in all, will be transferred to the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) as part of a gift from the collector Alice S. Kandell, a philanthropist who first travelled to Sikkim in the 1960s and subsequently amassed one of the most significant private holdings of Tibetan Buddhist art in North America. The shrine is expected to debut with a ceremony at Mia next summer.

The shrine features exquisite examples of Tibetan Buddhist art from the 14th to the 20th centuries, such as intricately carved vessels for churning yak-butter tea, gilded statues, immaculately preserved thangkas and rare instruments like Kanglings—traditional Tibetan trumpets made from human thigh bones. The donation makes up most of the remainder of Kandell’s collection. “Art belongs to the ages,” she says. “I was just their guardian for a brief period of time.”

Kandell has been dispersing her collection for over a decade. She gave 220 artefacts to the Smithsonian Institution in 2010, on the occasion of the exhibition In the Realm of the Buddha: The Tibetan Shrine from the Alice S. Kandell Collection, which was visited by 300,000 people in just three months. (Even the Dalai Lama approved of the show.)

A shrine assembled with objects from the 2010 donation has been exhibited at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art since 2017. It premiered as part of the acclaimed long-term exhibition Encountering the Buddha: Art and Practice Across Asia, which minimalist composer Philip Glass responded to with a 90-minute performance.

The presentation also caught the attention of Matthew Welch, the deputy director and chief curator at Mia. “I started waxing poetic about how great it was that the Smithsonian had a shrine, complete with Buddhist chanting and candlelight, and thought about the many problems around how museums deal with sacred objects,” Welch says. “We sometimes want to consider objects on their own aesthetic merits. But, during the process of placing them in museum galleries, we decontextualise them completely.” (Through a vetting process, it was determined that the objects in the shrine had been legally acquired from the families who previously owned them.)

Detail of the Tibetan Buddhist shrine that will soon be on display at the Minneapolis Institute of Art Photo: John Bigelow Taylor / Courtesy Alice S. Kandell

He adds, “I met Alice at the opening and she mentioned that she had another shrine back in New York. I saw it months later and very much wanted to pursue it to come to Minneapolis, which seemed impossible at the time.”

After Kandell’s years-long conversations with several museums, the Mia emerged as the right steward for the collection around 2021. Making a case for the transfer, Welch took Kandell to a Tibetan Buddhist monastery in Minneapolis, a city which houses the second-largest Tibetan American population after New York. He argued that the East Coast has its own shrines (at the Smithsonian and Rubin Museum of Art) and, although the Mia has one of the strongest collections of Chinese and Japanese art in the US, its Southeast Asian collection had lagged behind.

Kandell says she trusted the Mia’s level of expertise in handling Buddhist artefacts, critiquing other museums that, for example, exhibit thangkas with brocades cut off from the composition—a byproduct of dealers once making the pieces more “palatable” for sale in the Western market—or statues displayed without their bases, which she calls the “most sacred part of the piece, where prayers and precious gems are stored, and without which the piece is meaningless”.

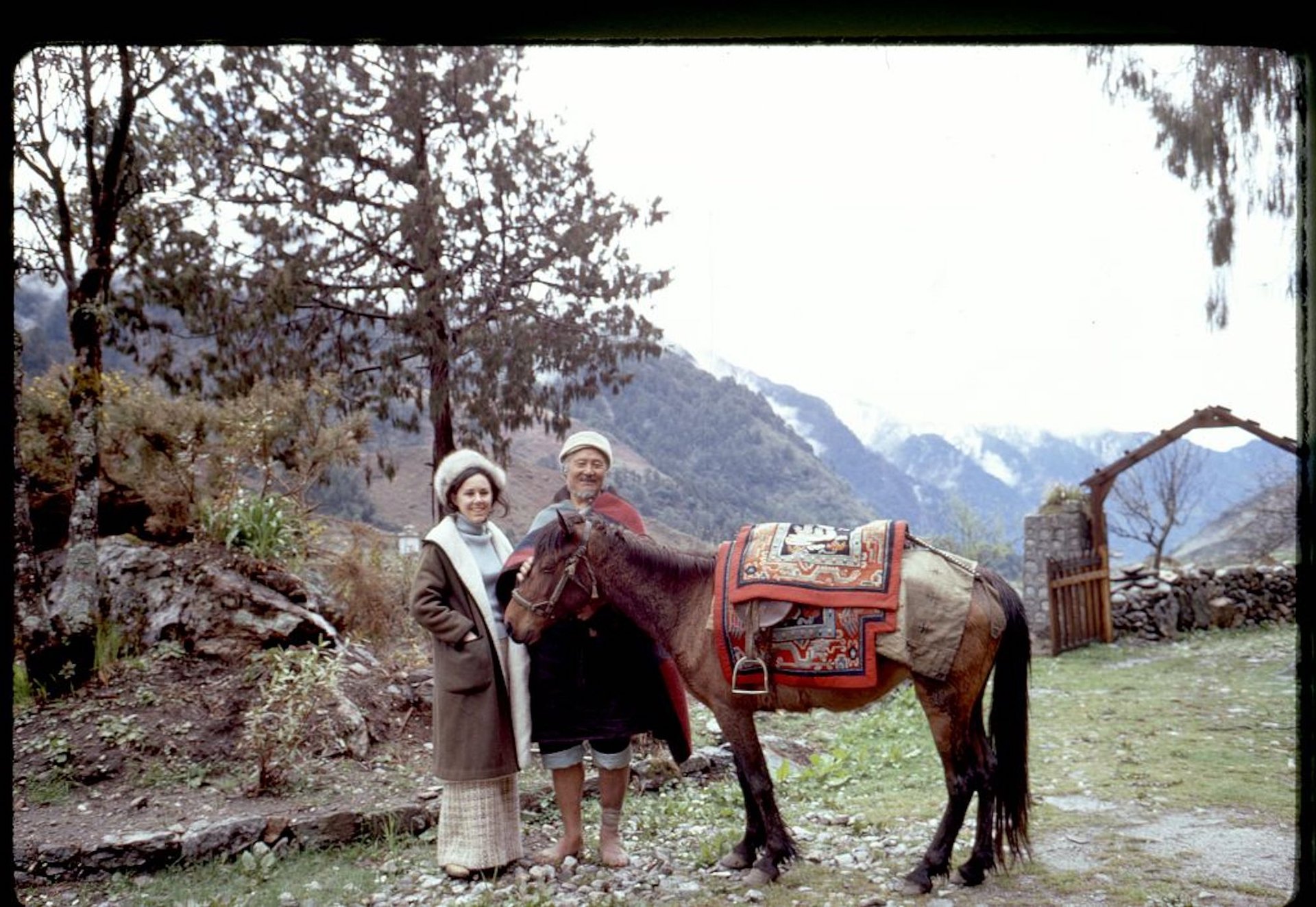

Kandell in Sikkim

A retired child psychologist, Kandell was a student at Harvard University in 1965, when she requested a three-week leave of absence to travel to Sikkim for the first time to attend the coronation of her friend Hope Cooke, an American who had married the crown prince of Sikkim, Palden Thondup Namgyal. (Her photographs from the coronation have been widely published.)

Kandell’s proximity to the royal family—and interest from the international press—led her to return to the kingdom several times, where she photographed religious ceremonies, traditional practices, occasions both formal and informal and the landscape and architecture of Sikkim before it was annexed by India in 1975. (Cooke returned to New York shortly after her husband was deposed; she divorced him in 1980.) Kandell has not returned to Sikkim since 1979, when she photographed the wedding of the princess Yangchen Dolma.

Alice S. Kandell with a villager and horse in Sikkim, May 1971 Photo: Courtesy the Library of Congress

In the years since, Kandell’s photographs from Sikkim have been exhibited at the Asia Society and the Camera Club of New York, and around 10,000 are held by the Library of Congress. Her images were published in the 1970 books Mountaintop Kingdom: Sikkim (with text by the travel writer Charlotte Y. Salisbury) and Sikkim: The Hidden Kingdom, among other publications.

With the rise of South Asian-inspired clothing in the 1970s, pieces from Kandell’s collection appeared in fashion editorials in Harper’s Bazaar, and have been used as departure points for jewellery and clothing lines by Van Cleef & Arpels and Bergdorf Goodman.

“I’ve always known that these objects don’t belong to me,” Kandell says. “I just happened to be in a position where I could bring them to America and keep them in a dedicated, sacred space. Even though I visit the shrine every night, otherwise no one really comes here. It’s time for them to be with the world.”