There are few scholars who have been dedicated to studying museological phenomena in India with the rigour and dedication of the art historian, author and institutional builder Kavita Singh. Writing on “the museum in an age of religious revivalism,” Singh and her collaborator, the art historian Saloni Mathur note:m“In India, it would seem that one cannot separate the domain of the secular and the religious in the way that one might in Europe, however tentatively. It is not merely that, for some visitors, museum objects housed in secular museums continue to be worthy of worship. Nor is it only that politicised religion finds the institutional form of the museum attractive—its alternation of resonance and wonder, sensuousness and education—and that politicised religion incorporates its technologies within the temple itself. It is, fundamentally, that the entire epistemological authority established by the museum through its secular avatars, where it declares itself as the teller of truths, is now proving useful for the reconstruction of society along religious lines.”

In the days following Kavita Singh’s death, the arts community across India celebrated her scholarship and collectively mourned her loss. As a founding figure of The School of Arts and Aesthetics in the historic Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), where she had taught since 2001, Singh developed a leading curriculum focusing on medieval miniatures and later periods of Mughal, Rajput and Deccan painting traditions, as well as museum studies shifting its axis from a colonial vantage toward studying the pluralism of India’s visual culture via ideas of custodianship, ritual, legacies of patronage, and post-partition memory cultures. Before her lasting engagement with JNU she was a visiting lecturer at the College of Art, New Delhi, and taught at the National Institute of Fashion Technology from 1991 to 1997.

Singh curated exhibitions at the San Diego Museum of Art, in California, and the National Museum of India, in New Delhi. During the inaugural course on curating and museum heritage that she conceived, I was part of a group of postgraduate students who worked under her guidance on the large-scale exhibition Where in the World: Indian art in the era of globalisation at Devi Art Foundation in 2009. She never separated the theory from practice, encouraging us to dedicate attention to installing art works, visit museum storages, and spend time in artists’ studios. Several young scholars mentored by Singh regularly contribute to international colloquia and publications on the civilisational expanse of Persian and Mughal miniature painting as well as transcultural visuality.

Singh was a compelling public speaker and delivered a range of major lectures including The Future of the Museum is Ethnographic at a conference held by the Pitt Rivers Museum and Keble College, Oxford, in 2013; and, by video streaming, the Slade Lectures in Fine Art for Cambridge University in April 2023. She joined the Getty Board of Trustees in 2020.

Singh’s essays such as “Remembering and Forgetting in the National Museum”, featured in an edited anthology published by Leuphana University in 2022, explore the multifaceted role of museums in the South Asian public sphere. The facets examined include how museums become sites to address historical traumas with an emphasis on Sikh and Tibetan communities. Furthermore, Singh critically addressed rising nationalism and religiosity in state-led cultural institutions and heritage monuments. Her book chapters and recent articles on the independent news website Scroll laid further emphasis on how artists of the Mughal and Rajput court ateliers applied strategies of subversion and appropriation, while foregrounding scholarly perspectives around the politics of representation. Among Singh’s numerous publications, her most recent volumes include Scent Upon a Southern Breeze: The Synaesthetic Arts of the Deccan (2018, Marg Publications), and Real Birds in Imagined Gardens: Mughal Painting Between Persia and Europe (2017, with Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles).

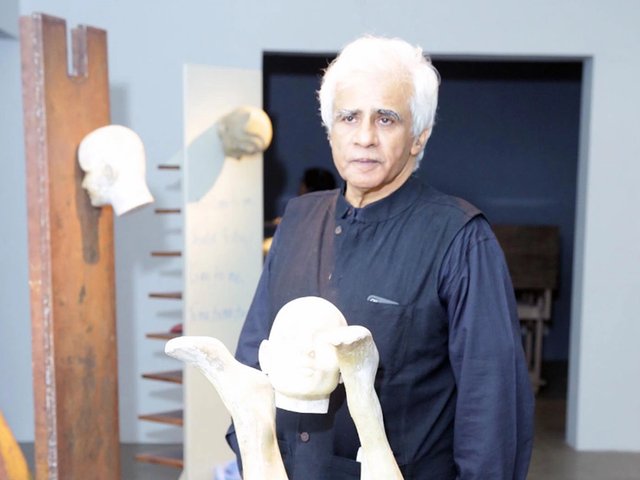

The art historian and artist Gulam Mohammed Sheikh met Singh when she was completing her postgraduate studies at Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda in 1987. He notes, “She would attend the MA Painting class of History of Painting I used to conduct around mid or late 1980s despite her being a student in the art history department. We stayed in touch after she left Baroda because I was keenly interested in her research on Phad [scroll] painting of Rajasthan she had initiated while she was in Baroda. She had identified all the characters of the folk deities Pabuji and Dev Narayan Phad made for performers to enact them. In 1987, I visited her in Jodhpur and she took me to see a rare performance on a hillock outside the village of Borunda in front of a large phad on an open ground. It was the time of dusk and sun and moon shared the sky, the Bhopi danced with a little lamp as the Bhopa sang the story”.

The artist Jitish Kallat recollects, “I met Kavita in the early 2000s. Many of us will remember her not only for the brilliant scholarship and her lasting legacy as an educator, but for her humour, generosity, radiant laughter and lightness of spirit. When I was forming my curatorial team in 2014 for the Kochi Biennale she was the first person I contacted for advice. She not only recommended some of her best students, but over the months continued to be in touch and offering any help I may need.”

In July 2017, Kavita Singh became the dean of the School of Arts & Aesthetics at JNU at a particularly turbulent time of political interference and communalisation on the rise. She challenged administrative measures such as a new attendance policy that curtailed academic freedom and the impending closure of research libraries, both in court and during her acceptance speech for the 2018 Infosys prize in Humanities, saying: “Today, things are bad; things are comically bad in my institutional home.”

Singh was removed from her position as the dean along with six other faculty members, which led to student protests and a lockdown of the campus, later followed by a high court order to reinstate them. After a two-year long health struggle with cancer, Singh delivered her final public lecture on 15 July on the invitation of Karwaan, a student-led Heritage Exploration Initiative. She will be remembered not only as a remarkable educator but also as a bold public intellectual astutely reflecting on the transformations of institutional establishments from the university to the museum.

Kavita Singh, born Kolkata 5 November 1964; Infosys Prize for Humanities 2018; married Arunava Sen (one son); died New Delhi 30 July 2023.