On the surface, the photography festival Rencontres d’Arles looks like a picture postcard; more than 30 exhibitions embedded into the very streets of the ancient French city, long sunsets dipping over the lush Provence landscape, birds roosting in the city’s enduring Roman ruins, an endless stream of young artists, from all over the world, mixing and drinking and talking in the bars by the Rhône, not far from where, in June 1889, Vincent van Gogh painted The Starry Night.

But is the city as bucolic as it seems? Because Rencontres d’Arles takes place in a moment of stress. The festival opened on 3 July as violent protests spread across France, sparked by the death of Nahel Merzouk, a 17-year-old boy of Algerian and Moroccan descent who was shot by a police officer during a traffic stop on 27 June in Nanterre, on the outskirts of Paris.

The riots have been particularly fierce in Marseille, the main transport link for the festival. Arles itself has faced disruption, unmasking, once again, the long-standing tensions between France’s affluent, chic and peaceful urban centres and its many troubled, disparate banlieues.

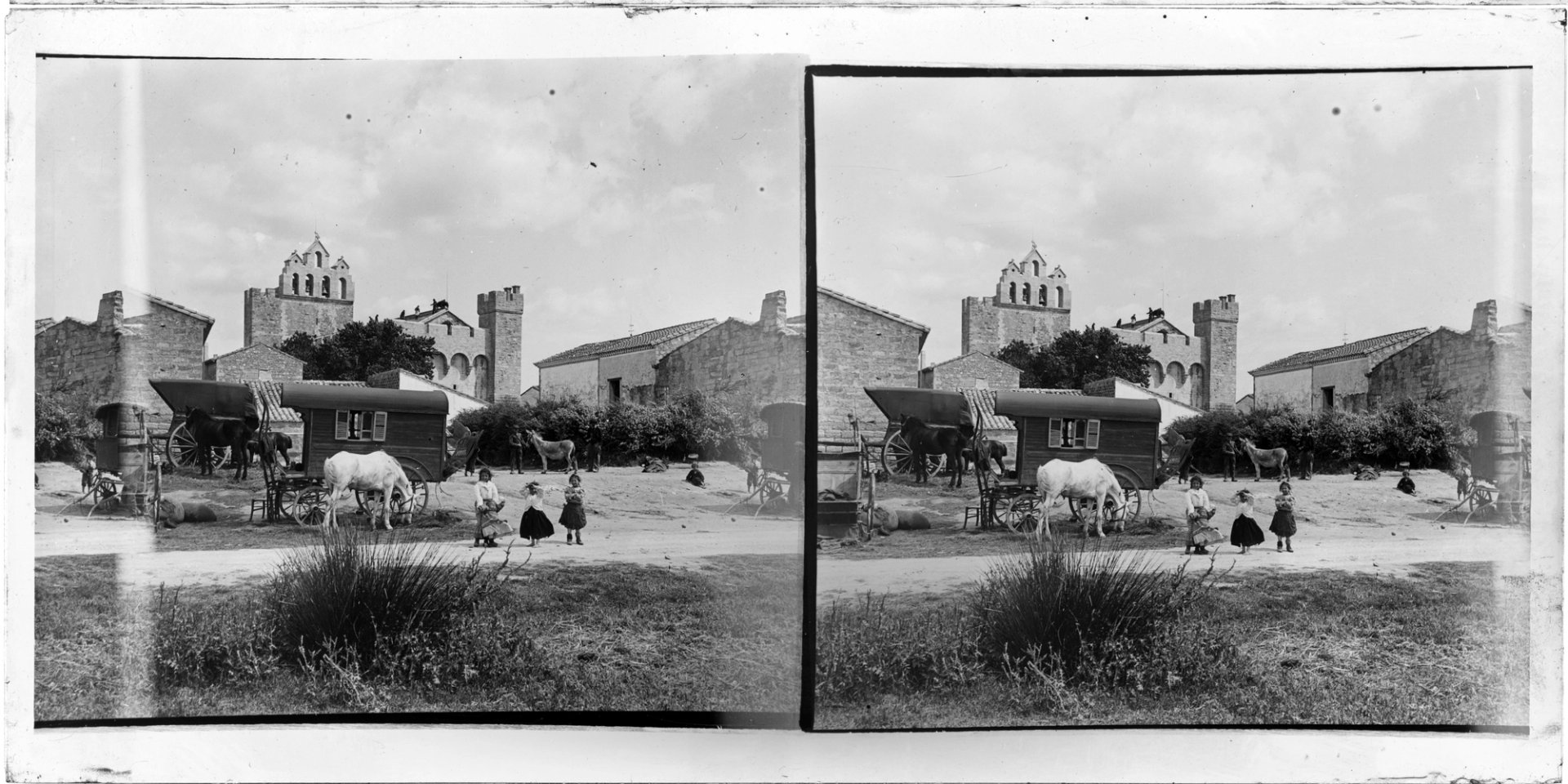

LUMA Arles now defines the city’s skyline. The cultural centre, designed by Frank Gehry and paid for by the philanthropist Maja Hoffman, is a monolith of glass and steel and stone; a hymn to what money can buy if you have enough of it. But Arles has a definite peripherique. It is not difficult to spot plenty of poverty here, a poverty which seems clearly delineated along racial lines. In 1988, Van Gogh painted Trailers, Gypsy camp near Arles, and a sizeable travelling community still call Arles their home. In recent elections, far-right nationalist candidates have found plenty of support in Arles’s voting booths.

Is the festival entirely insulated from its setting, or does it have the capacity and mentality to recognise it? The answer is yes—but you have to look beyond the headline acts.

Diane Arbus, Constellation, The Tower, Main Gallery, Luma Arles

Photo of all artworks © Adrian Deweerdt, courtesy the Estate of Diane Arbus Collection Maja Hoffmann / LUMA Foundation Photo

Rencontres d’Arles remains the place for living artists to get a retrospective. Get a survey of your work here and your spot in the establishment is secure. This year, the New York photographer Gregory Crewdson is handed the crown.

His work is shown alongside some big names from the annals of the medium, the biggest of which is Diane Arbus. Constellation, a roaming, amorphous exhibition of Arbus's portraits, takes up The Tower, the main gallery space of LUMA Arles.

Arbus’s work has been shown a lot recently; indeed, in London, the Hayward Gallery displayed many of the images shown here in 2019. But never before has the work been displayed with such audacity. Walking through the show is like walking through an Escher painting in which you encounter, sometimes again and again, her images of New York’s most marginalised figures. The portraits, ever more strange, are hung at oblique angles and at all levels, on tall, haphazard grids. Mirrors ring the room, allowing the observer to observe themself as they view her work. It’s a disconcerting experience, but it’s appropriate for Arbus. She used her subjects to mirror her own psyche, and, as such, one gets the sense of a manic, compulsive and obsessive artist. It is like being invited into Arbus’s brain.

In the Palais De L'archevêché, we find the perfect accompaniment; Assemblages, an exhibition of work by Arbus’s contemporary, the New York street artist Saul Leiter. He was born in 1923, the same year as Arbus. They often socialised together. But his gentle, tender portraits of New York couldn’t be more divergent. Are these really the same streets, in the same place, at the same time?

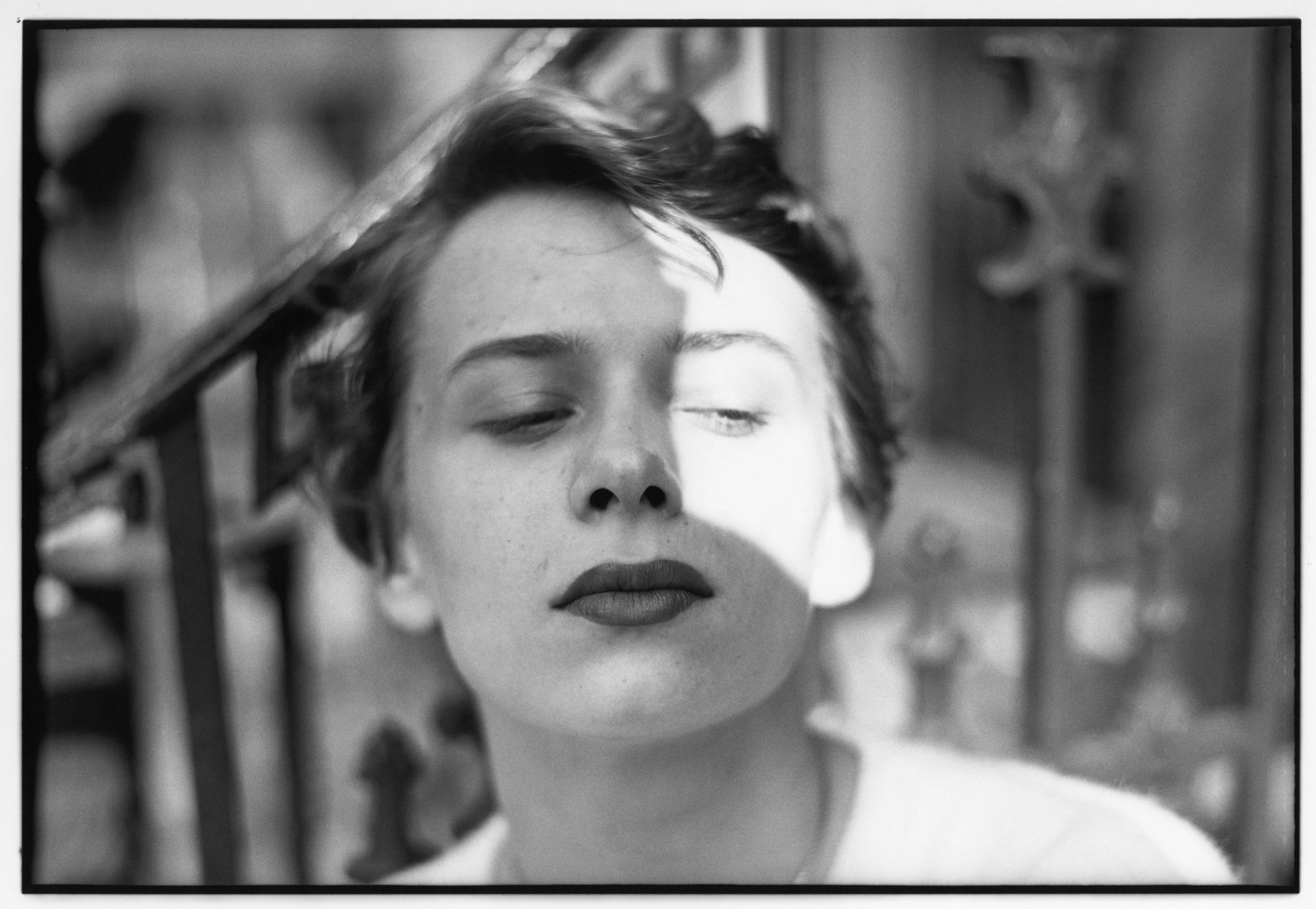

Saul Leiter. Ana, circa 1950. From the exhibition Assemblages, Rencontres d'Arles © Saul Leiter Foundation, courtesy Rencontres d'Arles

Leiter shot for Harper’s Bazaar throughout his adult life, but he never had much in the way of a gallery presence. He became, increasingly, a hermit, feeling marginalised and dismissed by the New York gatekeepers. They missed out on a photographer almost uniquely capable of sublime, sheer beauty, a quality amply demonstrated in Assemblages. Leiter, who rejected his Orthodox Jewish family to pursue photography, was an autodidact of art history; his photography was informed, in particular, by his deep readings of French impressionism and Japanese ma—the theory of negative space, "the nothingness where, in fact, everything happens", as the Japanese historian Kōtarō Iizawa terms it. Leiter's paintings are duly included in this intricate exhibition of his work. But the curator could have guided the viewer through the show a little more, displaying how such influences informed Leiter’s utterly distinct usage of colour, framing and bokeh (the art of blur).

Then there’s the Parisian polymath Agnes Varda, the late doyenne of the Nouvelle Vague. Tiny in physical stature, Varda was a giant of French culture. Her death is still recent; born in 1928, she died in March 2019. That being the case, it is understandable that the festival wants to recognise her passing. But the handling of Varda’s legacy here feels, to me, too partial. Two separate exhibitions of her work are on show; the first, titled A day without seeing a tree is a waste of a day, on show at LUMA Arles and curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, focuses on the artwork she made, as an ageing woman, for the 2003 edition of the Venice Biennale. The other, at Cloître Saint Trophime, showcases the photographs she took as a budding young artist in 1947 in Sète, the port town an hour from Arles. The photographs formed the basis for La Pointe Courte, her debut feature film, released when she was just 27. She’s also included in the group show Scrapbooks at the Espace Van Gogh, an exhibition looking at movie directors and their research materials. Each exhibition of Varda’s work has value, but they feel minor and incidental, not capable of capturing what a wonderfully emotive artist she was. She deserves a truly overarching retrospective.

Agnès Varda. Fishing lines at La Pointe Courte, positive view from the original negative, March-April 1953 © the Estate of Agnès Varda / Agnès Varda Photographic Archives deposited at the Institut pour la Photographie des Hauts-de-France

The headline shows go downhill from there. In Église Sainte-Anne, we are given Sosterkap, or ‘Sisterhood’, a group show of female artists from the Nordic countries. The show’s theme—to “explore the welfare state from a perspective of intersectional feminism”—disintegrates at the point of contact. It’s difficult to see how the work on the walls relates to this grand intent, while, too often, the portraits on show are shallow and bland or mere replicas of other series done better elsewhere.

Finally, there’s the blockbuster Crewdson show in La Mécanique Générale, a three-series retrospective which includes the first display of his new series, Eveningside. Crewdson has apparently spent his career “fleshing out a portrait of middle America,” we’re told. Middle America must be a very depressing place.

Crewdson, no doubt, has created compelling and enduring work; his series Beneath the Roses, from 2003 and not on show here, remains potent. But this exhibition cruelly reveals how repetitive and conservative his practice has become. From the beginning, his photographs paid too heavy a debt to Edward Hopper and New Hollywood, yet he continues to churn out derivative fare, yet another variation on a set theme, repeated over decades. The result is deadening.

Gregory Crewdson. Starkfield Lane, An Eclipse of Moths series, digital pigment print, 2018-2019 © Gregory Crewdson, courtesy Rencontres d'Arles

But push past the top billing and the festival comes alive. At the fringes of Rencontres d’Arles, smaller exhibitions by lesser-known artists feel urgent and of the moment, demonstrating that photography is the one truly global medium.

In the Louis Roederer Discovery Award, for example, there is strong bodies of work by artists from countries as disparate as India, Ecuador, Vietnam and Egypt. But the Discovery section is strong not because of its diversity per se. It’s strong because the work on show doesn’t feel tokenistic or exoticised.

Photography, at its worst, can feel like the creative splurging of a Westerner’s romantic dalliance with a country far from their own; parachute art, as it’s sometimes called. Arles, in years past, has been guilty of sometimes indulging this, while relegating artists from the global south, even ones who have gained acclaim in their own countries, to play second fiddle to known European names.

The Discovery of 2023 is anything but that; 80% of the artists on show comes from the global south, 90% of the work has been shot there. But this is not a group show about the expected concerns of ‘people of colour’.

If one had to capture the unifying theme of the show, it's the repudiation of migrancy as a burden. Migration, instead, is alchemical, uniquely capable of creating new ways of being. The show discusses "the distance between how we see ourselves and how we are seen by them,” says its curator, the Delhi-based Tanvi Mishra. “I become a person of colour and a migrant when I come to Europe from India,” says Mishra. “Back home, we don’t use these terms.”

Samantha Box. Portal, digital collage, printed as archival inkjet print, 2020 © Samantha Box, courtesy the Louis Roederer Discovery Award

Of particular note is Caribbean Dreams, by Samantha Box. The series mediates on Box’s identity with an unmoored thing; based in the US, raised in Jamaica, with Indian and African heritage, she considers her home to be the global diaspora. Her photography, then, considers the daily objects onto which we attach cultural currency; plants and vegetables, indigenous to her ancestral home in the Caribbean but considered alien in the US, are grown under artificial lights before being photographed with a lurid saturation. The plastic stickers attached to such commodified produce are pasted on top, interspersed with archive family portraits. These are packed, multivalent and complicated images, abundant with meaning and power.

Stronger still was the exhibition Light Of Saints. Set in Chapelle du Museon Arlaten, a desecrated Jesuit church from the 17th century, the exhibition is a humanistic history of the annual pilgrimage to the nearby Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, during which local Romani communities honour Saint Sara, the Black Madonna and patron saint of the Romani people. Some will see the setting of this informing, intimate exhibition as sacrilegious; for me, the intention was clear—we all worship the same God.

Also of note is the Abbaye de Montmajour exhibition 50 Years Through The Eyes Of Libération, a curated display of photography commissioned or published by Libération, starting from the newspaper’s founding in 1973—the newspaper turns 50 this year, and has become well-known in journalism circles for its willingness to break with news conventions, especially in its presentation of imagery. The show, then, mediates on the ever-evolving dynamic between documentary and fine art photography, mass media, conflict and political protest, a mash of relationships that seem to become more complex by the day.

Gaston Bouzanquet. View of the church and caravans, Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, 1911. From the exhibition Light of Saints © the Musée de la Camargue

Rencontres d’Arles’s opening week crescendoed with Nuit De l’Année, a late night party during which photographic montages were projected, at jaw-dropping scale, onto an abandoned warehouse a mile from the city centre. While the night had a rave-like atmosphere, the work on show was deadly serious.

A projection by Tori Ferenc, a press photographer for The Washington Post, showed, for example, the photographs a young group of teenagers took in the days after Russia's invasion of Ukraine. The group are from Melitopol, Ukraine and did what all groups of teenagers do best; they partied. In voiceover, we hear them reflect on a year of war and the toll it has taken on them after they initially plunged, head-long, into hedonism, even as their city began to be flattened by Russian ordnance.

This was juxtaposed with the meditative images, taken by the Iranian photographer Mahka Eslami, of an Iranian refugee making his way to Coventry in the UK, even as he recovered from the news his best friend and toddler child were killed after a small boat sunk in the English Channel.

Each series kicked like a cart horse, driving home, in the Provence night, how delicate and forceful photography can be.

- Rencontres d'Arles runs until 24 September