When the Chinese Canadian Museum opened the doors of its permanent home in Vancouver on Canada Day, there was a sense of both homecoming and historical acknowledgement. The opening marked exactly 100 years since the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring the migration of Chinese people to Canada, which had gone into effect on 1 July 1923. The museum’s inaugural exhibition, The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act (until 30 June 2024), collects the stories and experiences of individual migrants from both government records and community archives.

The new museum is situated in the Wing Sang Building, the oldest edifice in Vancouver’s Chinatown and former residence of Chinese merchant Yip Sang. It was last home to the Rennie Museum, which showcased the collection of real estate marketer and philanthropist Bob Rennie. In 2004 Rennie engaged local firms Francl Architecture and McFarlane Green Biggar Architecture + Design for a five-year heritage renovation to create a space for his collection and corporate offices. In February 2022, he announced that his foundation would donate C$7.8m ($14m) to “ensure the Chinese Canadian Museum is sustainable in its mission”. Grace Wong, board chair of the Chinese Canadian Museum, thanked him “for being such a wonderful custodian for this very special building and its history”.

The Chinese Canadian Museum Ian Kobylanski/Koby Photography

This gift from Rennie in a rapidly gentrifying Chinatown, together with funding from the provincial government—which officially apologised in 2014 for the "head tax" paid by Chinese migrants to get into the country (the price peaked at C$500 in 1903)—were part of a kind of reparations process, says Melissa Karmen Lee, chief executive of the Chinese Canadian Museum. She says that between 1885 and 1923, approximately 81,000 Chinese immigrants paid the tax, and the total collected was C$23m. “In today’s terms, that would be C$1bn,” she notes. And although the head tax was a federal law, the money went into provincial coffers as immigrants arrived largely on the West Coast. Coincidentally, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) also cost C$23m, Lee says. “So, in essence, the Chinese not only built the railway, but they also paid for it.”

The museum’s mission statement phrases its aim as “honouring the history, contributions, and heritage of Chinese Canadians”, but Lee says there will be a variety of programming. “We plan to show a mix of heritage and art exhibitions,” she says. “We believe we can showcase the history of Chinese Canadians, but also contemporary culture and art. All of these exhibition genres are access points for visitors to further engage with our mandate to elevate and uplift Chinese Canadian voices.”

Lee says one of her aims is to show that Chinese identity is not “homogeneous or monolithic”. To that end, the ground floor exhibition features a wall of photos of Chinese Canadians who came from the international diaspora—from Mauritius to India to Zanzibar. Like the second-floor exhibition, The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act, curated by Catherine Clement, the ground-level show draws heavily on community archives.

“We hope, as we move forward, that we have more people contribute to populating the whole wall,” Lee says. In an adjoining first-floor area, archival photographs document the connections between Chinese and First Nations peoples—who were both excluded as non-citizens who could not vote until 1947 and 1960, respectively. These are augmented by video interviews with subjects including the half-Chinese Musqueam elder Larry Grant and a specially commissioned piece by Musqueam Coast Salish artist Susan Point that welcomes visitors at the entrance.

Currently, much of the first floor's eastern wall is covered by a Marlene Yuen mural highlighting aspects of Chinese Canadian life—from seniors doing tai chi in front of the CN Tower in Toronto to CPR trains and community cafés.

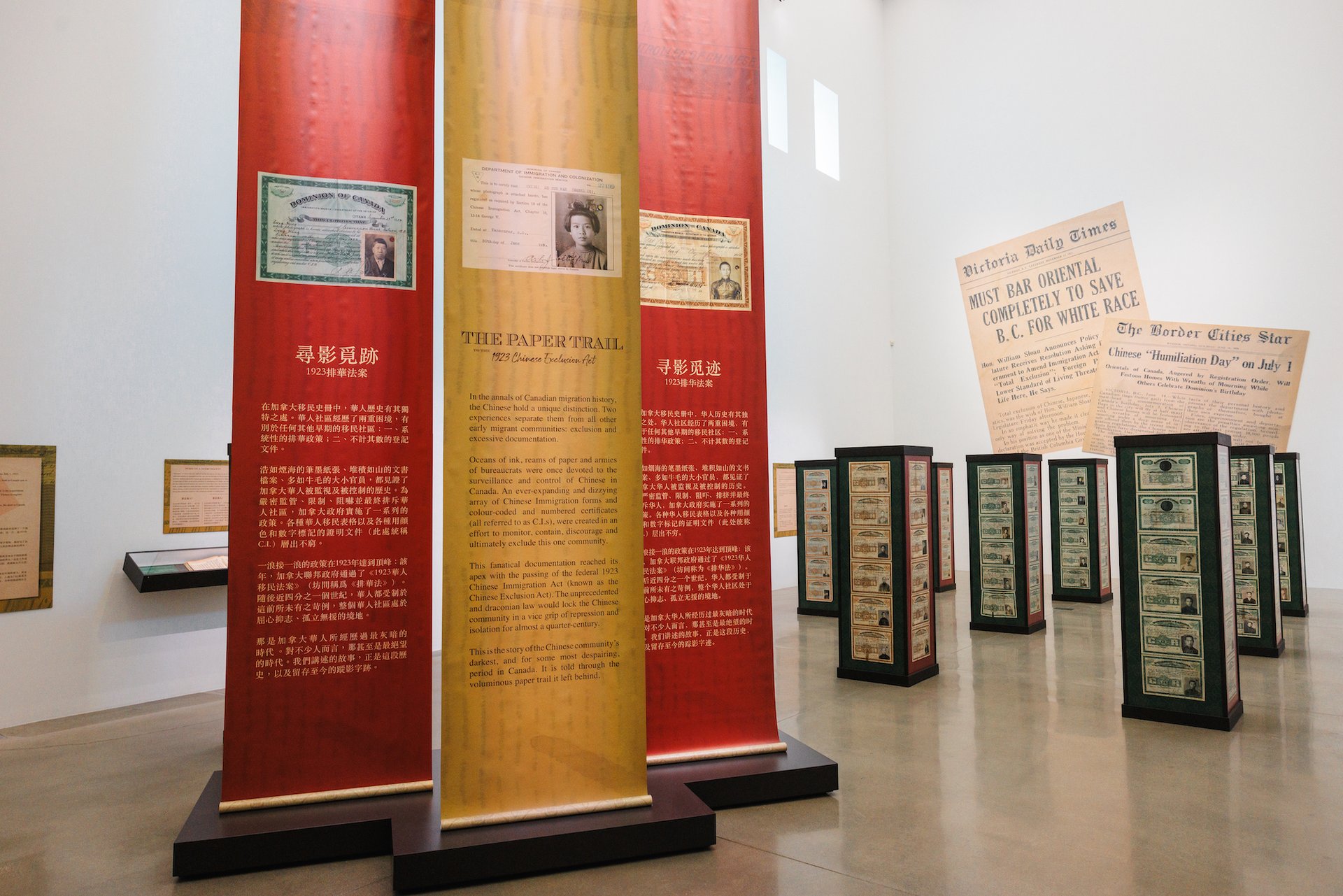

Installation view of The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act Ian Kobylanski/Koby Photography

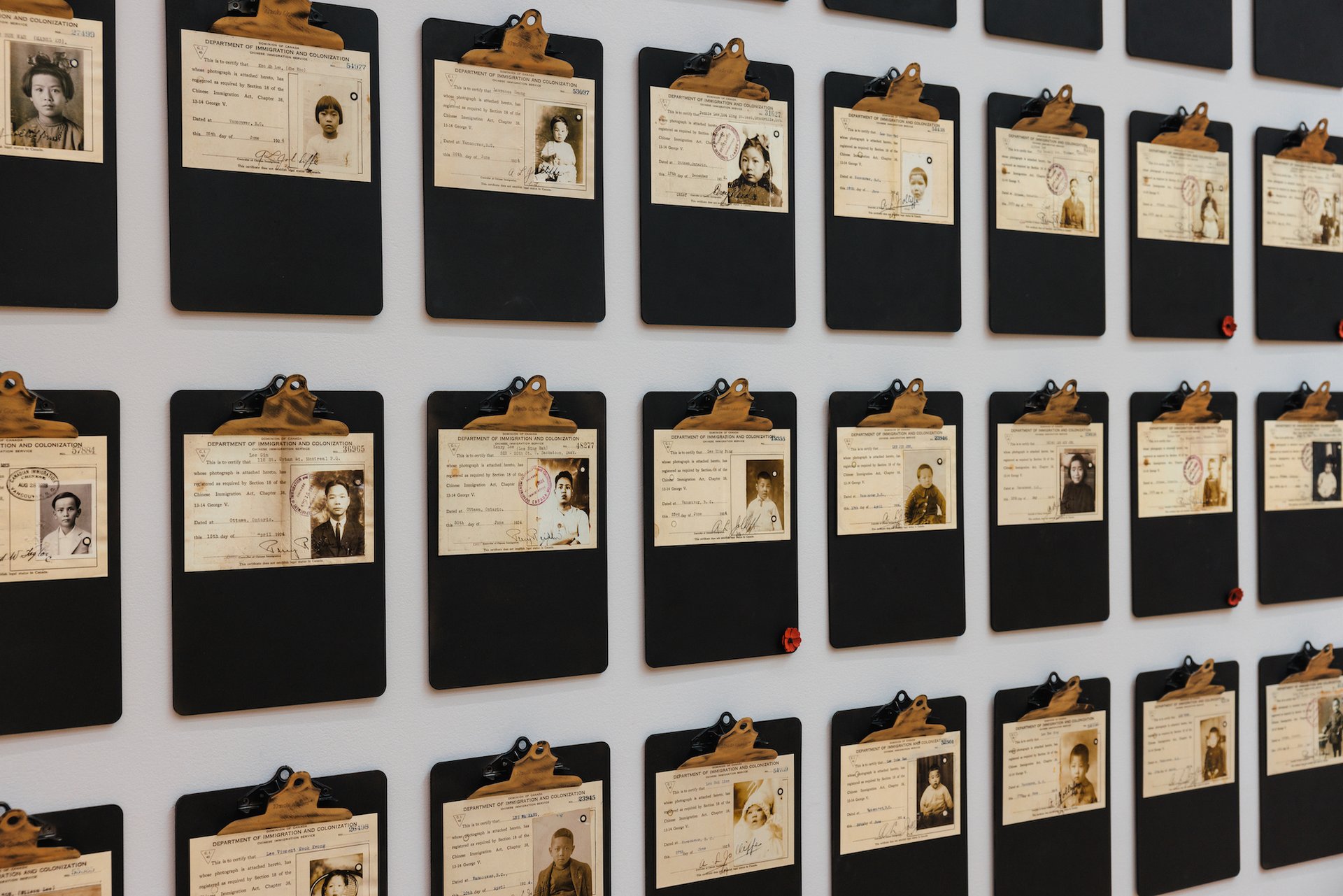

On the second floor, The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act incorporates hundreds of Chinese Immigration certificates—the most ever displayed publicly in one show—all of them crowdsourced from Chinese Canadian families from around the country.

“In Canadian history, the Chinese hold two unique distinctions that separate them from all other early migrant communities: exclusion and excessive documentation,” Clement says. “This is the story of the Chinese community’s darkest period in Canada told through the voluminous paper trail it left behind.”

Installation view of The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act Ian Kobylanski/Koby Photography

The exhibition’s strength lies in the telling details of personal stories that pierce through the sheer volume of records. From a rare single woman who arrived as a maid and was forced into an unhappy marriage with an older man to the story of a Chinese man wrongfully convicted of the murder of a white police officer, to stories of men who had wives and families back in China spending much of their adult lives isolated and alone.

“The stories we have uncovered involved hundreds of hours of original research,” Clement says. “We scoured the pages of old Chinese and English newspapers, sifted through clan society archives, examined personal correspondences, waded through coroners’ reports, culled through newly released government records and tapped the memories of hundreds of families across every region of Canada.”

Now, those memories have been given voice by a powerful inaugural exhibition in a new museum that offers timely food for thought—not only on Chinese Canadian history but more broadly on issues of national identity and belonging.

- The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act, until 30 June 2024, Chinese Canadian Museum, Vancouver