The Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston has unveiled the painting Customers Conversing in a Tavern (1671) by Dutch Golden Age painter Adriaen van Ostade—which had once been acquired by associates of Adolf Hitler during the Second World War—after coming to an agreement with descendants of the painting’s former owners and a couple that bought the painting in 1992.

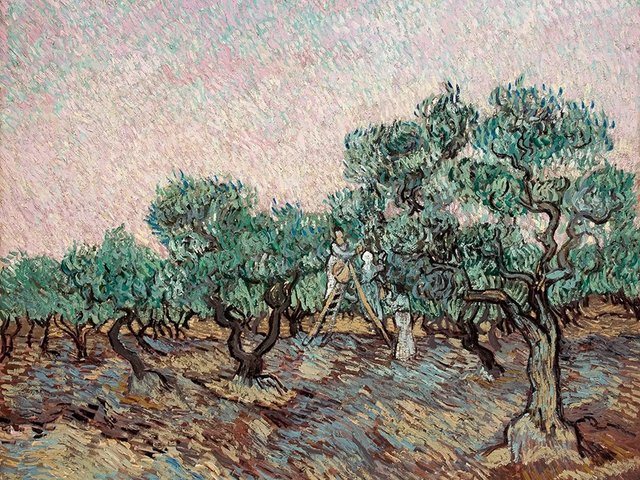

The panel, which shows two groups of people smoking and drinking in a tavern alongside a dog and chickens, has been installed in the MFA Boston’s Dutch and Flemish galleries alongside other works by Van Ostade and his pupil Cornelis Bega from the museum’s collection.

Customers Conversing in a Tavern is one of 28 Dutch and Flemish paintings pledged to the museum in 2017 by collectors Susan and Matthew Weatherbie, who purchased the painting in 1992. The Weatherbies were unaware of the painting’s history during the Second World War at the time of the sale. The Weatherbies and the museum will pay the heirs of two Jewish art dealers who jointly filed a claim on the painting, according to the The Boston Globe. The deal will allow the Weatherbies to remain owners of the work they pledged to the museum in 2017.

“We are happy that these longstanding ownership issues have been resolved so amicably, and we are delighted to display Customers Conversing in a Tavern at the MFA so that it can be shared with the public,” the Weatherbies said in a statement.

The Weatherbies first became aware of the painting’s history six years ago, after Victoria Reed, senior curator of provenance at the museum, discovered its inclusion on the German Lost Art Foundation’s database during research into the couple’s historic gift to the museum, according to the Globe.

In 1937, the Van Ostade panel was in the collection of Paul Graupe et Cie., a Paris-based gallery run by the Jewish art dealer Paul Graupe. Graupe fled Paris for Switzerland in 1939 before eventually relocating to the US. Graupe left his gallery stock in Nazi-occupied Paris, but before leaving Europe, asked his business partner Arthur Goldschmidt for help saving his gallery inventory. Graupe hoped Customers Conversing in a Tavern could be sent to Switzerland for safekeeping for the duration of the war, the MFA Boston said.

Goldschmidt fled to the south of France in 1940, which then was not yet occupied by Axis forces. The following year, Goldschmidt brokered a sale of Customers Conversing in a Tavern to Karl Haberstock, a Berlin art dealer who worked on behalf of Hitler and was permitted to travel between occupied and unoccupied regions of France.

The sale of Customers Conversing in a Tavern and other works of art from the gallery without his approval angered Graube, according to the Globe, and Graupe and Goldschmidt broke off their business partnership within months. Goldschmidt emigrated to Cuba later in 1941 before moving to the US in 1946.

“It’s not a black-and-white story,” Reed told the Globe. “It’s hard to neatly categorise the decisions of a Jewish emigré art dealer, who is living in the south of France, trying to survive and make his way out of Europe.”

In April 1941, Haberstock sold Customers Conversing in a Tavern to Hitler’s art adviser Hans Posse, and the painting was selected for the Führermuseum, a museum Hitler planned to build in Linz, Austria. The panel was recovered by Allied forces after the end of the Second World War from the Austrian Altaussee salt mine, where Nazi Germany stored more than 6,500 works of looted art. Graupe chased property claims for the missing artwork after the end of the war, and early on included the Ostade painting among his claimed work, though he later removed the listings for unknown reasons. By 1951, the painting had not been officially claimed, and was auctioned by the government of France. Graupe died in Germany in 1953, and it’s unclear if he ever knew what happened to the painting.

“I think it’s wonderful that we can put the painting on view,” Reed told the Globe. “The goal in redressing all of these material losses is, yes, to right a wrong, but it’s also to preserve the memory of the people who lost this property.”

Museums, galleries and private collectors have come under mounting pressure to restitute works with murky provenances. This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Washington Conference, a 1998 summit held to determine guiding principles for the restitution of art looted by Nazi Germany before and during the Second World War.

Earlier this month, the northern German city of Hagen restituted a landscape painting by Auguste Renoir to the heirs of its former owner, a Jewish banker persecuted by the Nazis, before repurchasing it so it can stay on display at the Osthaus Museum, where it has been since 1989.