With 40 museums packed into its 37 square kilometres, Basel is a mecca for art lovers all year round. The Kunstmuseum Basel is one of the world’s oldest museums, with origins dating back to the 17th century. Home to more than 300,000 artworks spanning eight centuries, it testifies to the generations of prosperity and stability the city has enjoyed—largely uninterrupted by the wars and catastrophes that devastated museums in other parts of Europe.

Basel’s historic wealth from commerce and industry helped Ernst Beyeler to rise from modest beginnings to become one of the world’s foremost art dealers. Together with his wife, Hildy Beyeler, he amassed an extraordinary personal collection of Modern art. This has been housed since 1997 at the Renzo Piano-designed Fondation Beyeler in Riehen on the outskirts of town—arguably one of the prettiest museums anywhere. Visitors can hop on a 25-minute tram ride there from Basel’s main train station (15 minutes from the Messeplatz just outside Art Basel).

Between these two museums there is something for everyone. But visitors who like their art very old will also enjoy the Antikenmuseum Basel, Switzerland’s biggest antiquities collection. Those who seek out the ultra new—preferably digital—should head to the HEK (House of Electronic Arts), which offers crypto brunches and “make your own avatar” workshops. For art that is interactive and quirky, look no further than the Museum Tinguely, devoted to the Basel-raised pioneer of kinetic sculpture (whose mechanical fountain in front of the theatre is a city landmark, too.)

Holbein's Portrait of Bonifacius Amerbach (1519) Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Buhler

Hans Holbein the Younger’s Portrait of Bonifacius Amerbach (1519), Kunstmuseum Basel

It’s hard to overstate the importance of this portrait to Basel. Before he moved to England and became Henry VIII’s court painter, Hans Holbein the Younger lived in the Swiss city from 1515 to 1532. He counted Bonifacius Amerbach, the son of a Basel printer, and the Dutch philosopher Erasmus (whose portrait by Holbein is also in the Kunstmuseum) among his friends. The city purchased the Amerbach collection in 1661, laying the foundations for the Kunstmuseum. The collection’s 15 Holbein portraits included this depiction of Amerbach as a young man, about to leave for plague-ridden France to continue his studies in law.

Konrad Witz’s St Bartholomew from the Mirror of Human Salvation altarpiece (around 1435), Kunstmuseum Basel

The 15th-century German painter Konrad Witz, who spent most of his life in Basel, is believed to have created the Mirror of Human Salvation altarpiece for the church of St Leonard. The altarpiece was at some point sawn into sections, and two panels are missing from the ensemble now in the Kunstmuseum. The figure of St Bartholomew, who featured on the exterior, illustrates Witz’s mastery of light and shadow.

Picasso’s Seated Harlequin (1923) Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Buhler / © ProLitteris, Zurich

Pablo Picasso’s Seated Harlequin (1923), Kunstmuseum Basel

Part of a series of harlequins that Picasso painted using the same model and a costume given to him by Jean Cocteau, this may be one of the most democratically acquired artworks in history. In 1967, the businessman who had loaned it to the Kunstmuseum, Peter Staechelin, found himself financially liable for a fatal plane crash. He decided to sell off Seated Harlequin and another Picasso displayed at the museum, The Two Brothers (1906). Local residents led a heated campaign for the city to buy the paintings—slogans included “All You Need is Pablo”—and the “yes” vote won a referendum later that year. Picasso was so touched he gave Basel four more works.

Ferdinand Hodler’s Lake Geneva, Seen From Chexbres (1905), Kunstmuseum Basel

Though today he is perhaps the closest thing Switzerland has to a “national painter”, Ferdinand Hodler was very much an artist’s artist in his lifetime. A trailblazer who pointed the way towards Expressionism for many younger painters, he struggled financially until the early 20th century. Hodler’s enigmatic Symbolist paintings of people performed less well on the art market than landscapes such as this—one of a series of 13 paintings he made from Chexbres, a village between Lausanne and Montreux.

Franz Marc’s Animal Destinies (1913) Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Buhler

Franz Marc’s Animal Destinies (1913), Kunstmuseum Basel

This masterwork by the German Expressionist Franz Marc is an apocalyptic vision that almost seems to anticipate its own turbulent history. Trees are ripped from the soil and horses in flight foam at the mouth in a canvas painted a year before the outbreak of the First World War. Marc was killed by a grenade in the Battle of Verdun in 1916. A year after his death, the painting was damaged in a fire. Marc’s friend Paul Klee restored it carefully, using muted browns to distinguish his work from the original vivid blues, reds and greens. The Nazis confiscated the painting as “degenerate” art from a museum in Halle, Germany. Basel acquired it from the art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt, who worked with the Nazis, in 1939.

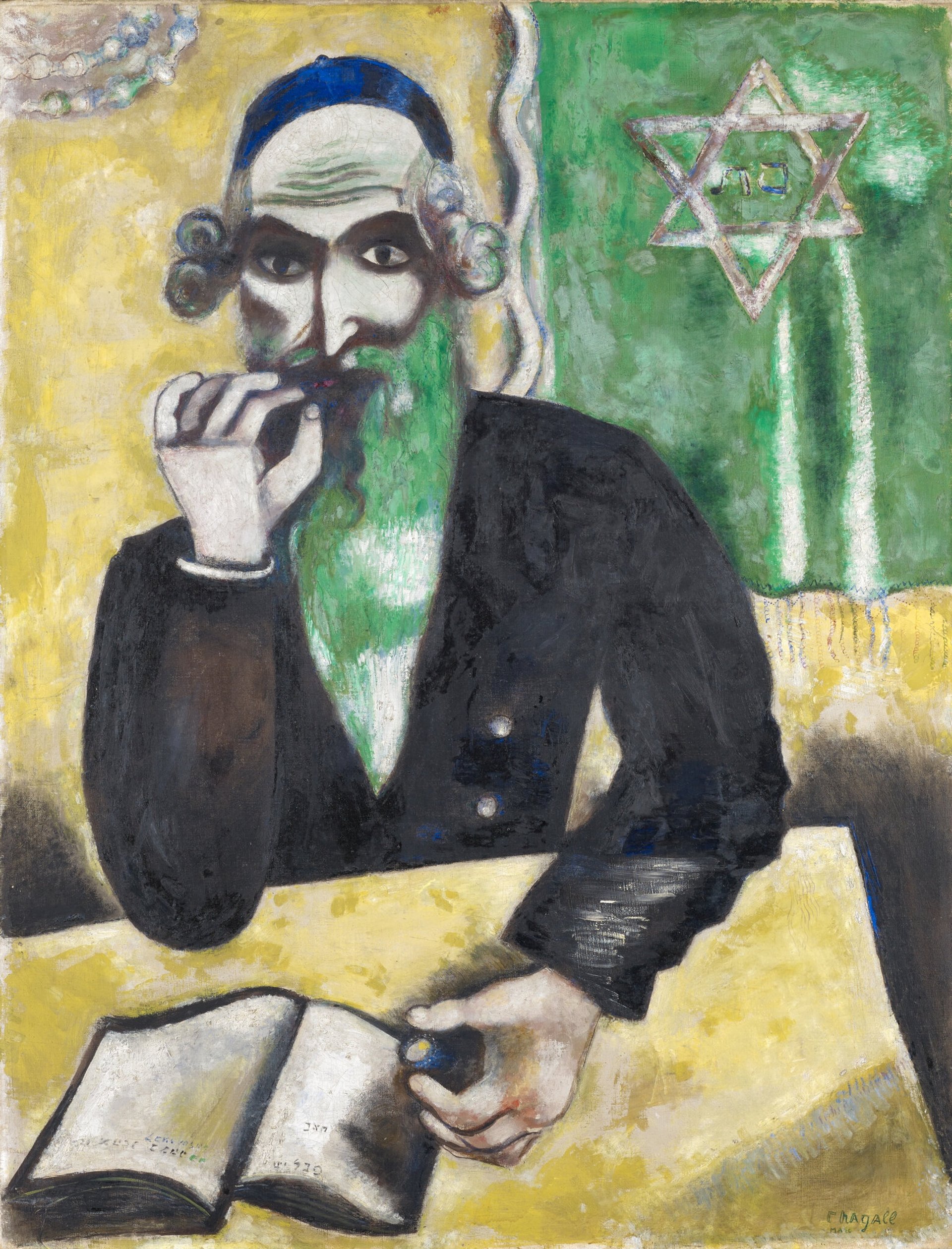

Marc Chagall’s The Pinch of Snuff (Rabbi) (1923-26) Kunstmuseum Basel / © ProLitteris, Zurich

Marc Chagall’s The Pinch of Snuff (Rabbi) (1923-26), Kunstmuseum Basel

Georg Schmidt, the canny Kunstmuseum director who purchased Animal Destinies, also bought this vibrant Chagall portrait at a Lucerne auction of “degenerate” art confiscated from German museums. The painting had previously been paraded through Mannheim on a cart and shown in shop windows to incite public mockery. Schmidt recognised it as one of Chagall’s best works. Like many paintings produced during the artist’s second sojourn in Paris, it recalls his devoutly Jewish upbringing in his native Russia.

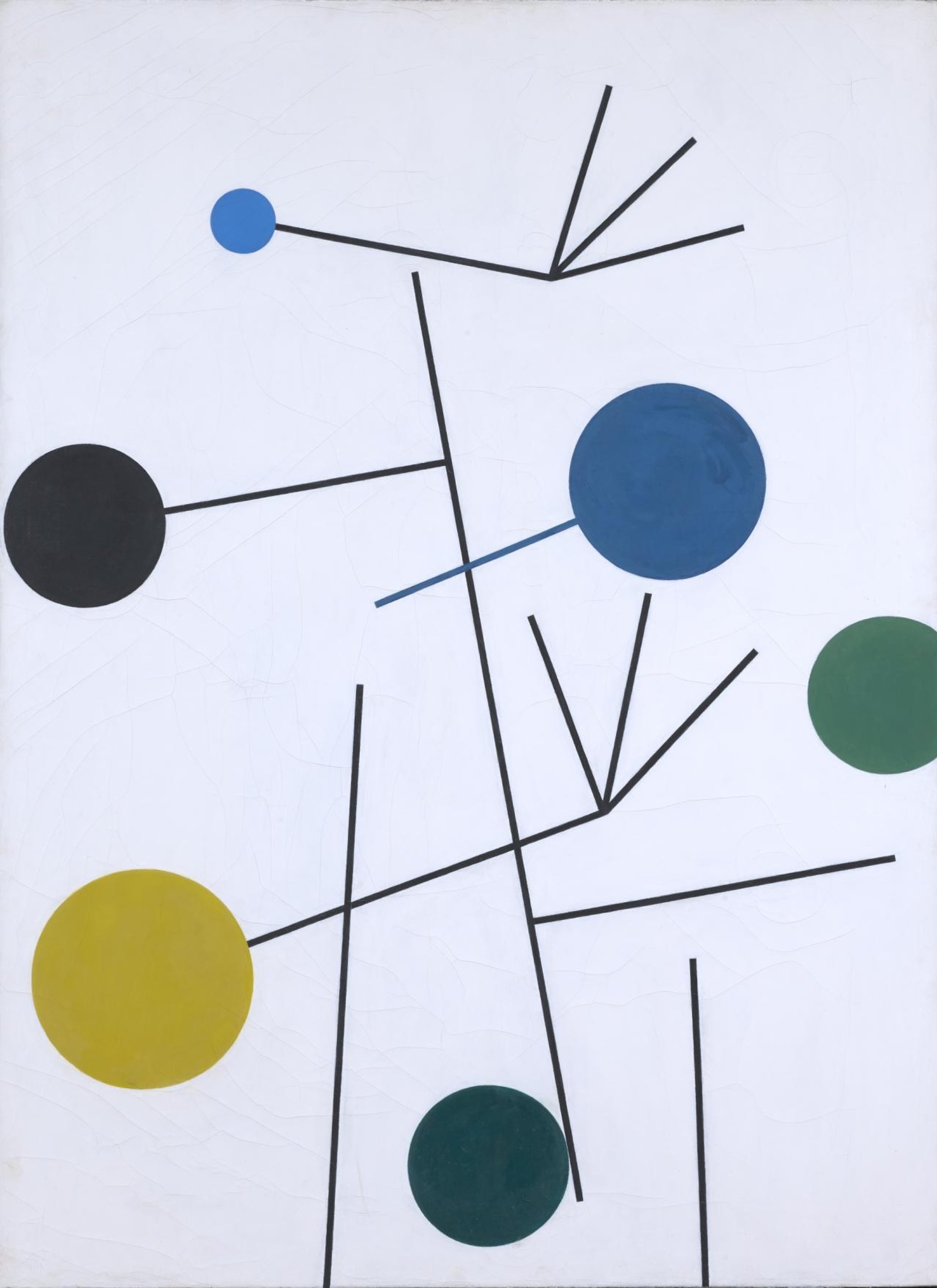

Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s Equilibrium (1934) Kunstmuseum Basel, Martin P. Buhler

Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s Equilibrium (1934), Kunstmuseum Basel

Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s dazzling artistic range was the subject of an exhibition held at the Kunstmuseum in 2021, encompassing marionettes, beaded bags, cushion covers, rugs, stained glass, jewellery, costumes, architecture designs and performance art. The Kunstmuseum collection has several of her precisely balanced yet playful abstract paintings.

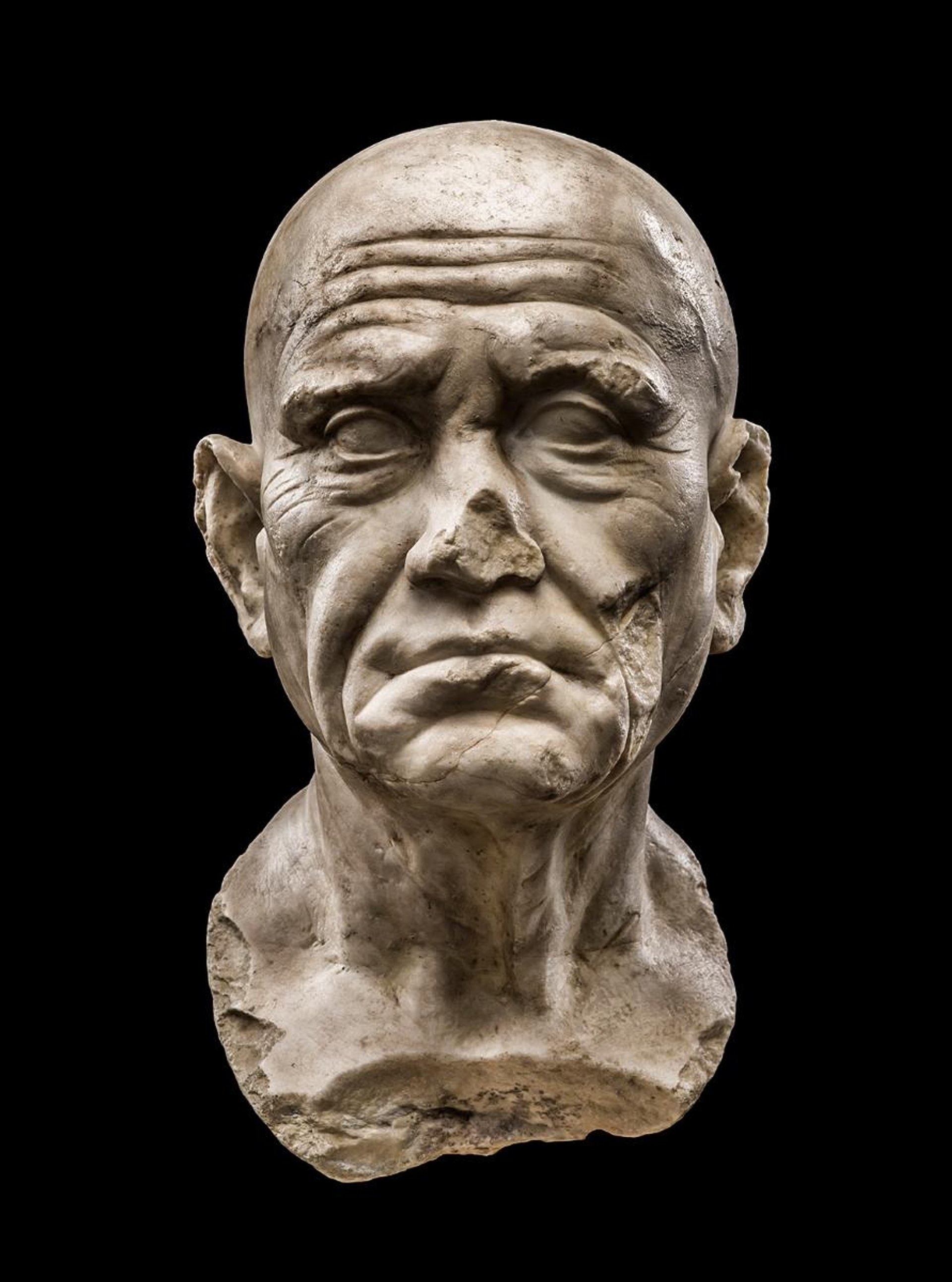

© Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig

Head of a Republican, Roman, (around 60 BC), Antikenmuseum Basel, St. Alban-Graben 5

This remarkable marble sculpture—possibly of a venerable Roman senator—is far removed from the idealised portrayals of gods and heroes we associate with classical art. Instead it combines an unsparing representation of the ravages of age—the furrowed brow, sagging cheeks, deep worry lines around the eyes—with a bearing suggesting extraordinary strength, energy and purpose.

Henri Rousseau’s The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope (1898/1905), Fondation Beyeler, Riehen

Probably painted in 1898, this fantasy jungle with its lush ornamental foliage was the first painting by the customs officer and self-taught artist Henri Rousseau to be accepted for the Salon d’Automne exhibition in Paris in 1905. It was also the first of his works to be reproduced in a magazine and one of the few he managed to sell on the market.

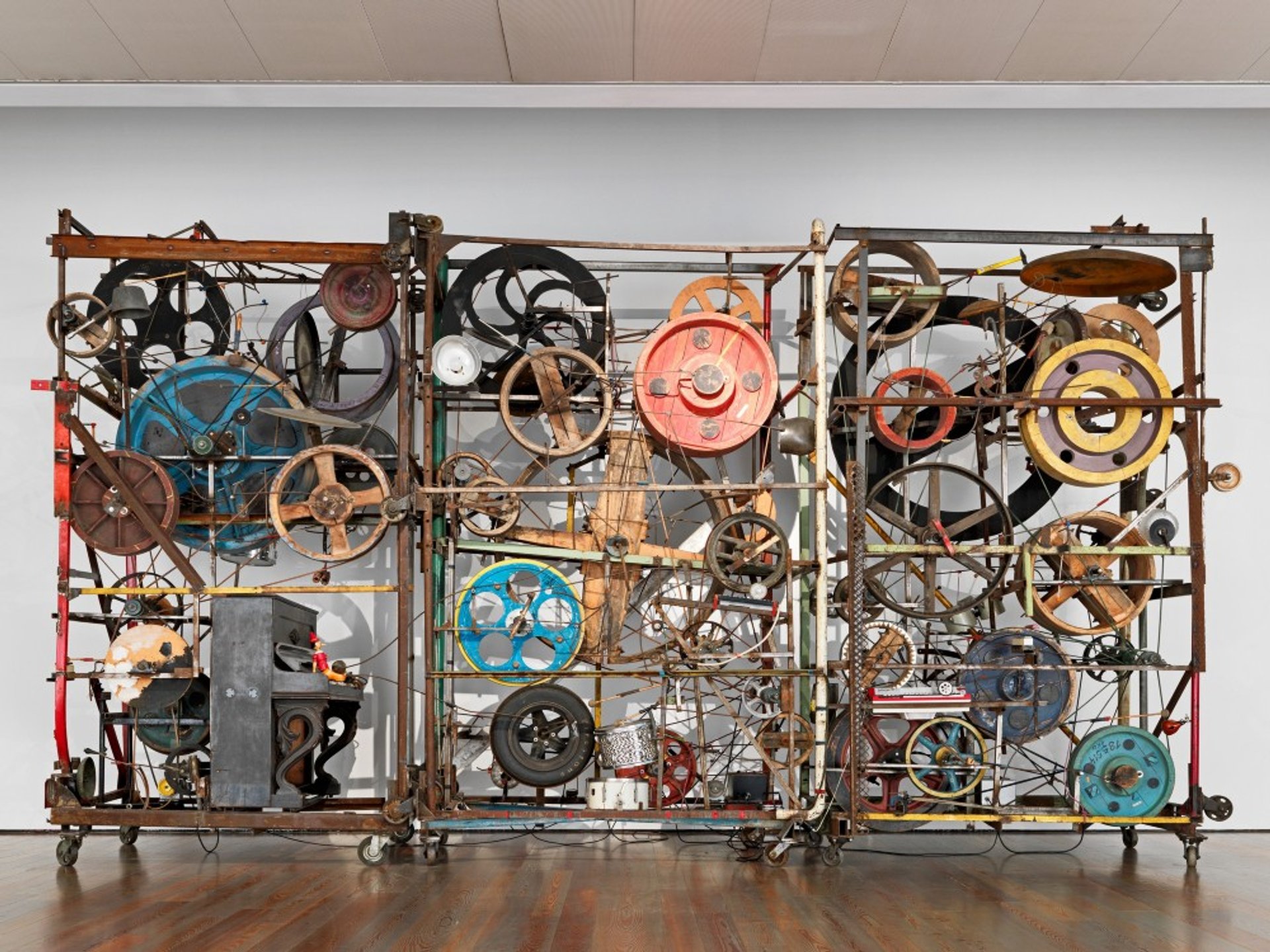

Jean Tinguely’s Méta-Harmonie II (1979) Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation, permanent loan to Museum Tinguely / © ProLitteris, Zurich

Jean Tinguely’s Méta-Harmonie II (1979), Museum Tinguely

Jean Tinguely’s clanking, squealing and altogether mesmerising kinetic contraption is made of wheels and cogs, musical instruments including percussion and a piano, and household items such as a clog and a puppet. The sound sculpture is designed to be heard as well as seen—and underwent a comprehensive restoration a few years ago to return it to its original cacophonous state.