Dominique-Charles Janssens inspects Van Gogh’s Garden at Auvers (June 1890) in a bank safe

Credit: Institut Van Gogh, Auvers

For over thirty years Dominique Janssens has been struggling to fulfil Van Gogh’s dream: to exhibit a painting in the inn where the artist lived for his final ten weeks. This spring he came tantalisingly close to achieving the audacious goal. Garden in Auvers (June 1890) was promised on short-term loan by the private owner, who is believed to have been a Frenchman resident in Switzerland.

In June 1890 Vincent had written to his brother Theo: “One day or another I believe I’ll find a way to do an exhibition of my own in a café.” He was then staying in the Auberge Ravoux, in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise. Vincent lodged in a small garret bedroom, above the café on the ground floor. His letter to Theo was probably written downstairs, a glass of wine at hand.

Auberge Ravoux/Maison de Van Gogh, Auvers-sur-Oise

Photo: Institut Van Gogh, Auvers

In 1987 Janssens bought the building and its annexes, which until then had remained a café in the centre of the village, just north-west of Paris. He painstakingly restored the historic interior, opening it up to visitors as a tribute to the artist.

The highlight of the visit is entering the tiny attic bedroom where Van Gogh died on 29 July 1890, two days after shooting himself. It is left empty, except for a simple chair.

Van Gogh’s bedroom, Auberge Ravoux/Maison de Van Gogh

Credit: Institut Van Gogh, Auvers

“Visitors come not as tourists, but as pilgrims”, Janssens says. Having completed the refurbishment, he turned his mind towards fulfilling the artist’s dream, to display a Van Gogh painting. For security reasons, it would have very difficult to hang it in the downstairs café, which opens onto the street. Instead a high-security glass cabinet was built upstairs in the much more secure bedroom. At seven square metres, Janssens describes it as “the smallest museum in the world”.

His latest plan was that Garden in Auvers would be displayed for two months, until the end of April. Although security was already very tight, earlier this year Janssens spent €400,000 on an upgrade, including a seven-ton armoured door, a sophisticated surveillance system and the strictest fire precautions. When I visited the inn a few weeks ago the security seemed to be what one might expect in a major museum. Insurance cover was negotiated through the leading Brussels-based art specialist Eeckman.

Just four days before Garden at Auvers was due to be delivered Janssens received bad news: the owner’s agent was questioning the arrangements. Since then there have been intensive discussions, but so far the issues remain unresolved. Garden at Auvers is still hidden away in a bank safe.

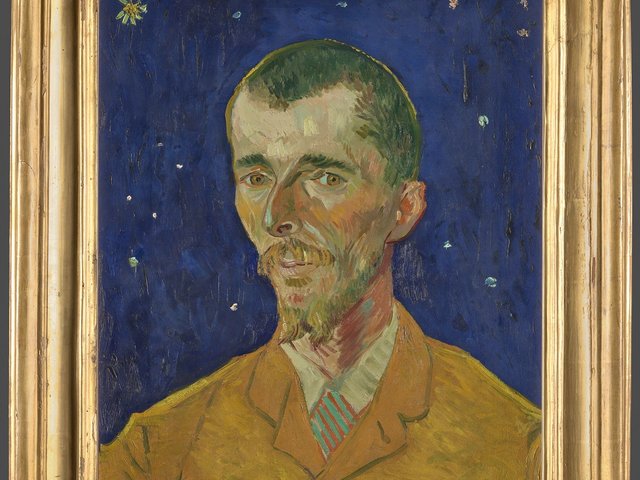

Van Gogh’s Garden at Auvers (Jardin à Auvers) (June 1890)

Credit: private collection

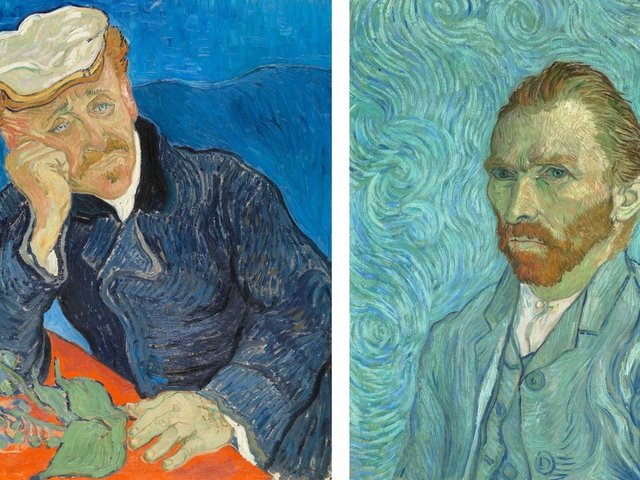

Garden at Auvers is unusual among Van Gogh’s late work, since it is more decorative and abstract than most of his landscapes, composed partly of blocks of patterned colours with dotted highlights. The perspective suggests a bird’s eye view. The composition may well have been inspired by a visit to the garden of the deceased artist Charles-François Daubigny, whose widow lived five minutes’ walk from the inn.

The painting has had a particularly chequered history in recent decades. In 1992 it was bought by the banker Jean-Marc Vernes for the equivalent of $10m. After his death, four years later, the picture was offered for auction in Paris, but shortly before the sale there were claims in the media that it was a fake.

This was understandable, because it was an atypical Van Gogh and at that point there was uncertainty about its provenance. Potential buyers were wary about buying a painting whose authenticity had been so publicly questioned. It failed to sell.

Since then further research has clearly established that questions about its status were quite unfounded. Garden at Auvers has been authenticated by Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, the recognised authority on the artist’s work, as well as by the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

Although unreported, five years ago the banker’s heirs, Pierre and Edith Vernes, sold Garden at Auvers through the Parisian auctioneer Marc-Arthur Kohn, in a private sale. It went to an anonymous buyer. He died a few months ago and ownership then apparently passed to his two daughters.

But there is another element to complicate the Garden at Auvers story. In 1989 the French government registered the painting as a national treasure, which means that it cannot be exported from France, considerably reducing its financial value. Without this restriction a Van Gogh landscape of this quality might well be worth over €150m, but as it cannot leave France permanently it is now valued at around half this sum.

Garden at Auvers was not the first painting which Janssens tried to borrow or buy to fulfil Van Gogh’s dream.

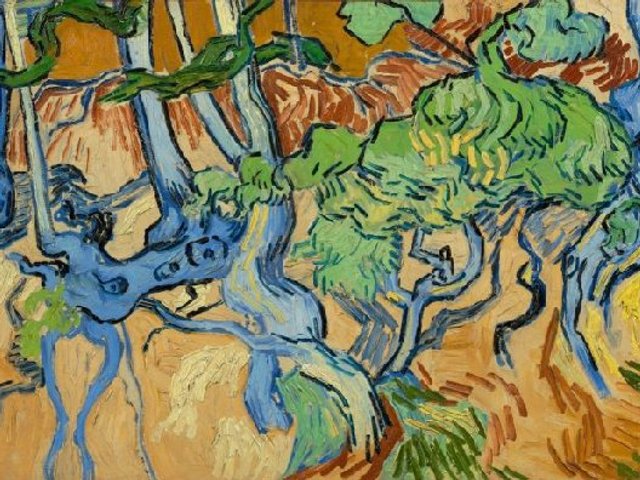

Van Gogh’s The Red Vineyard (November 1888)

Credit: Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

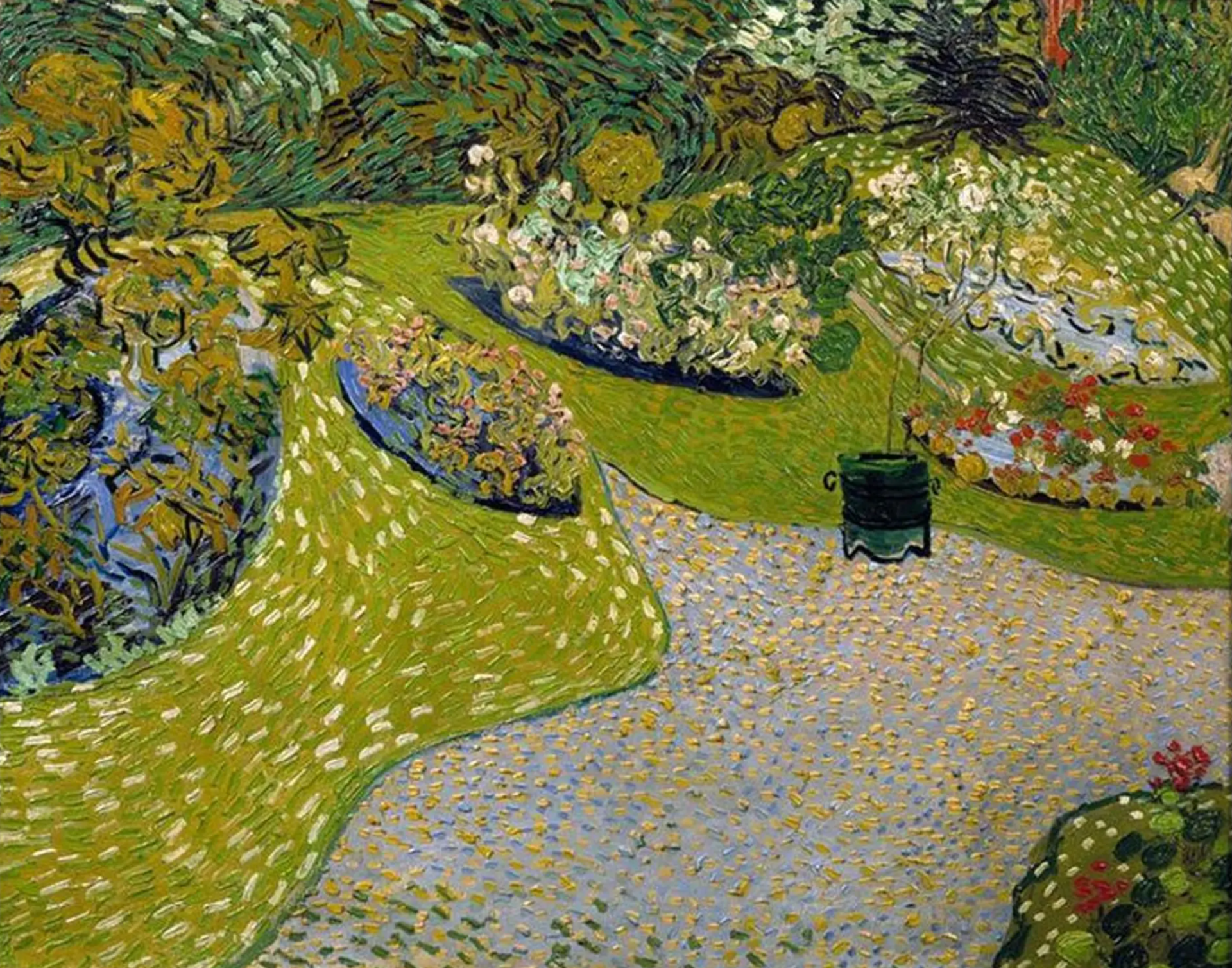

Van Gogh’s Landscape with Train (June 1890)

Credit: Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

In the 1990s he nearly secured the loan of a work from the Pushkin Museum in Moscow: either The Red Vineyard (November 1888), the only painting Van Gogh ever sold, or Landscape with Train (June 1890). However, the international arrangement needed to be overseen by the French authorities. They blocked a loan on the grounds that the inn was not a recognised museum.

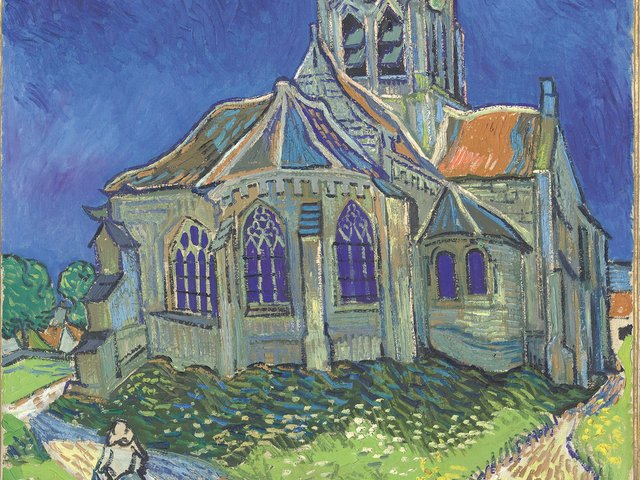

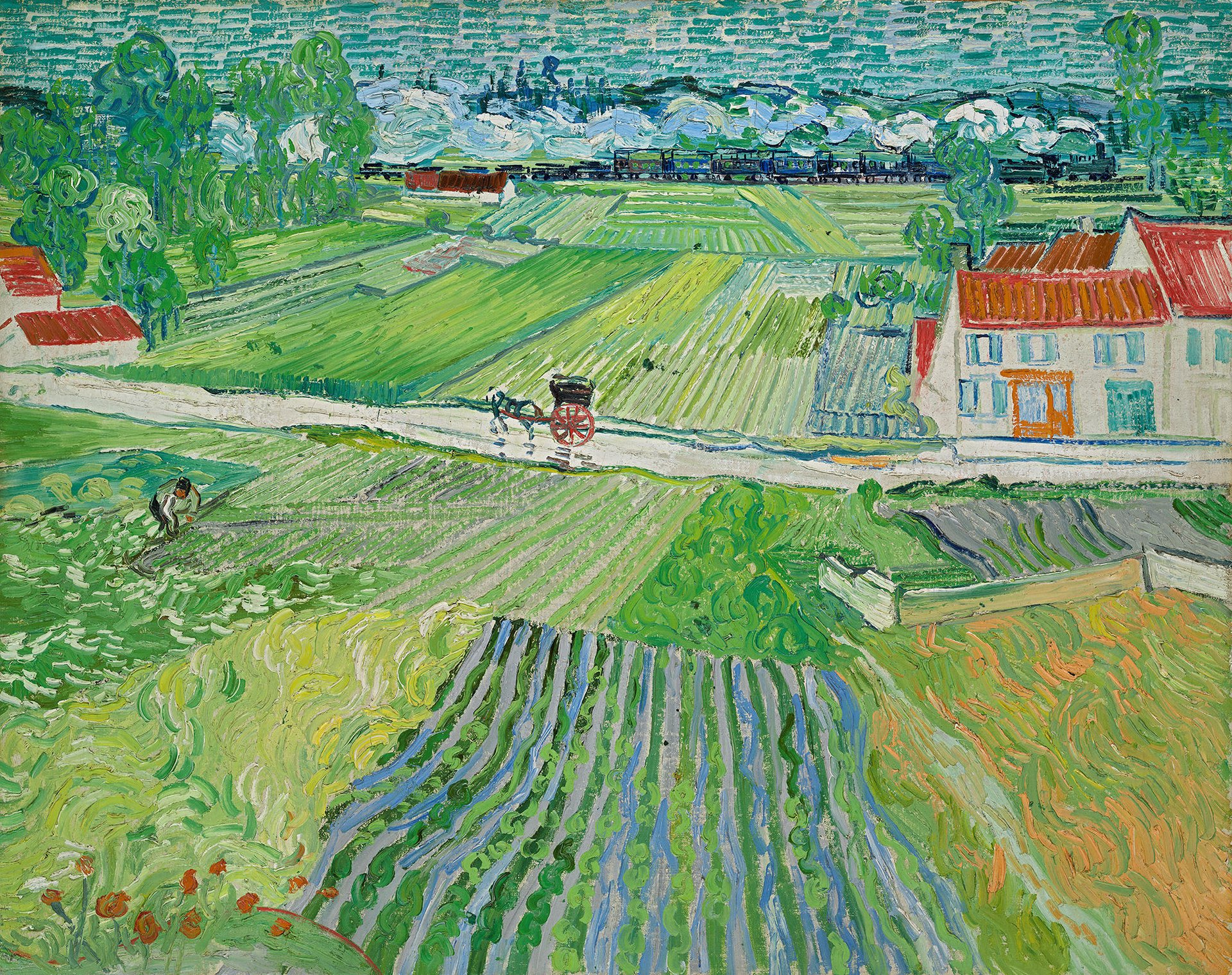

Van Gogh’s The Fields (July 1890)

Credit: private collection

In the early 2000s Janssens was optimistic about buying, rather than borrowing, a privately owned Auvers painting,The Fields (July 1890). Despite having secured corporate support from an American bank, the price eventually proved an insurmountable barrier because of the financial crisis. In 2017 the private owner put the picture up for auction at Sotheby’s, with an estimate of $28–35m, but it failed to sell.

Janssens with the reverse of Garden at Auvers, showing the wooden stretcher and frame

Credit: Institut Van Gogh, Auvers

Despite these setbacks, the indefatigable Janssens has not given up: “I am still hoping that it may be possible to borrow Garden at Auvers or, if it is sold, from a new owner. And I have my eye on several other of Van Gogh’s Auvers paintings which are in private collections. I am determined to realise his dream.”

Meanwhile Garden at Auvers will shortly go on loan, but to two museums, thanks partly to Janssens’s contacts. The painting is expected to be displayed in the coming Van Gogh in Auvers: His Final Months exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum (12 May-3 September) and the Musée d’Orsay (3 October-4 February 2024).