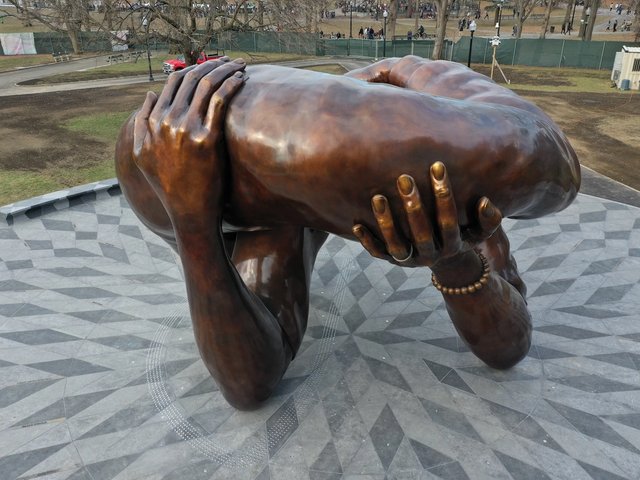

As devastating put-downs go, Seneca Scott’s response to Hank Willis Thomas’s memorial honouring Martin Luther King Jr and his wife Coretta Scott King takes some beating. The Embrace, a sculpture Thomas made with MASS Design group based on a photograph of the couple hugging, was unveiled on Boston Common in January. But Scott, a cousin of Coretta’s, wrote that it looks “like a pair of hands hugging a beefy penis”. Contrast this with the words of Arndrea Waters King—the wife of Martin Luther King III, the civil rights leaders’ eldest son—who described it as “a remarkable statement of mutual love and solidarity”.

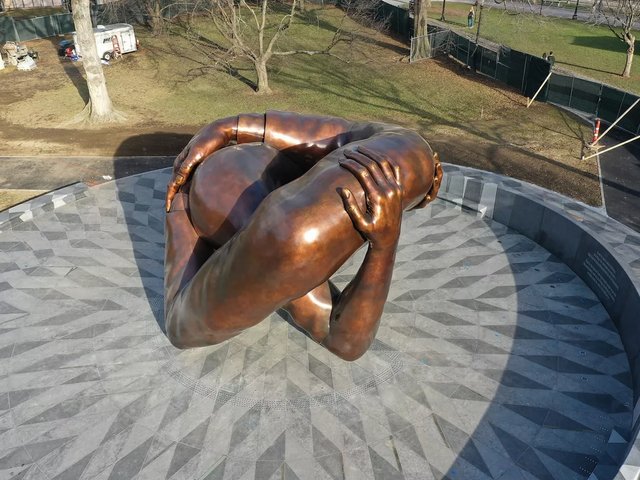

A similar debate greeted the completion, after many years’ delay, of Anish Kapoor’s latest mirrored globule, dubbed the “half bean” or “mini bean”, in honour of his much larger monolith, Cloud Gate (2004), in Chicago. The New York work sits squidged beneath an apartment block, 56 Leonard, designed by Herzog & de Meuron and known as the “Jenga Tower”. Writing for ARTnews, Alex Greenberger described the sculpture as “the tacky fast-fashion cousin of its couture Chicago counterpart”, while a Chicago Sun-Times editorial declared Cloud Gate to be the “better bean”, which adds “a little fresh ammunition in the ongoing cultural war between Chicago and New York”.

Anish Kapoor's 'bean' at the corner of Leonard and Church streets in New York City © Benjamin Sutton

Public sculpture is often lauded for bringing art out of hallowed gallery spaces—but it’s also fiendishly difficult to get right

Public sculpture is often lauded for bringing art out of hallowed gallery spaces—or forward from the arts pages to the front pages and the funnies—and inviting everyone to see and opine on it. But it’s also fiendishly difficult to get right—and all the more so because it is often meant to be permanent, and frequently costs eye-watering sums. That Thomas’s sculpture is already inviting knob gags doesn’t bode well.

It’s no coincidence that many successful public projects have been temporary, whether in the programmes of Creative Time and the Public Art Fund in the US, or on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, London. Impermanence frees up artists and permits more risk-taking. But even here, there are problems. A report in the Guardian revealed that three-quarters of former Fourth Plinth commissions are in storage, unwanted and racking up huge storage costs, their debate-igniting days just a memory.

Rachel Whiteread, who made Monument for the Fourth Plinth in 2001, told the paper that the plinth had “done its time” as a site for sculpture. But Monument exposed the commission’s limitations: I loved it when I saw it, but as an inverted resin “ghost” of the plinth, it was utterly site-specific. Where else could it have worked? The irony is that Whiteread made a truly great public sculpture in House (1993), the concrete cast of a Victorian home in East London, which prompted controversy in the UK and was lamentably demolished within months.

But House has a legacy—in photographs, of course, but also in the memories and testimonies of those who saw it, which keep it quietly alive. What matters most with public sculpture is its ability to sustain its power and meaning beyond its immediate physical presence.

It is true of Cloud Gate: it has site-specific effects, but also transcends them in people’s imagination. That its smaller New York sibling is shoved beneath a luxury building is an apt metaphor, in that it is inextricable from the condos above it, one of which Kapoor reportedly bought for $13.6m in 2016. How can art be transcendent, and speak to a broad audience, amid such conspicuous plenty?