Where in the world are the cultural capitals of the future? Probably in Asia and the Middle East, at least according to researchers investigating the global boom in major cultural buildings over the past 30 years.

With expansive ambitions and deep pockets, Shenzhen, Abu Dhabi and Doha are foremost among the cities constructing state-of-the-art new museums, opera houses and theatres to rival the old-world centres of New York, London and Paris. A study underway at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, seen exclusively by The Art Newspaper, heralds a “geographical shift from the established cities of high culture” in the Global North towards Asian metropolises, led by China and the Gulf. “Our analysis allows us to see a batch of new global cities of culture emerge,” write geographers David Gogishvili and Martin Müller, two of the academics undertaking the study, in a forthcoming academic paper.

Their research draws on data relating to 438 “major” cultural buildings that opened in 58 countries between 1990 and 2019 (to avoid the anomalies of the Covid-19 pandemic). The buildings were defined as “major” if they cost at least $100m (in 2019 values), or have a footprint of at least 20,000 sq. m—roughly the size of the Guggenheim Bilbao, the much-imitated icon of culture-led regeneration—or a minimum seated capacity of 1,500 for performing arts venues.

Cultural capitalism

Gogishvili and Müller see the proliferation of such mega-structures as evidence of “the global rise of cultural capitalism” at the turn of the 21st century. Purposefully spectacular arts buildings, often designed by a handful of “starchitects”, have become powerful symbols for cities competing in the global race for “attention, reputation, tourists and investment”, they write.

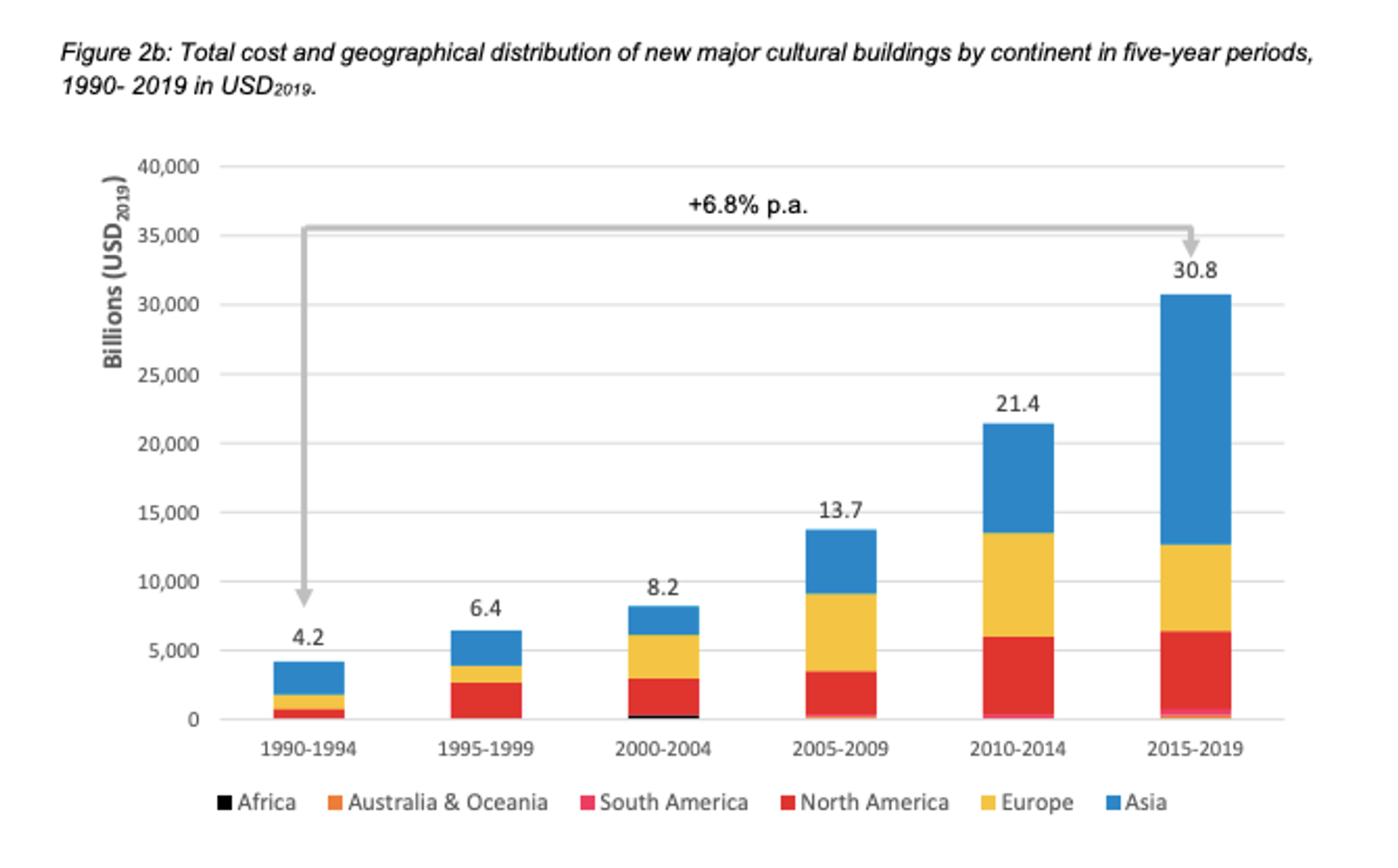

Close to $84.7bn in investment has been poured into the projects sampled, which, taken, together cover an area of almost 17 sq. km, the size of a small country. The five most expensive come with a price tag of more than $1bn each: in descending order, the Getty Center in Los Angeles, the Millennium Dome (now called the O2) in London, the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center in Athens.

The number of these flagship arts venues has exploded during the “intense period of globalisation” since 1990, Gogishvili says in an interview. Boosted by the end of the Cold War and China’s accelerating economic reforms, a trend that began in the Global North has spread eastwards. The study finds that Europe held the biggest share of major projects in the early 1990s—ten out of a global total of 24 in that five-year span, compared with seven each in Asia and North America. But Asia has taken a decisive lead since the mid-2000s. Of the 150 major venues that opened from 2015 to 2019, 84 were in Asia, against 32 in Europe and 30 in North America.

Each continent’s total expenditure on new cultural buildings costing more than $100m, from 1990 to 2019

Credit: David Gogishvili, Martin Müller

Asia rising

China has overwhelmingly driven this shift, completing 131 projects during the period surveyed, or 30% of the sample (the US is in second place, with 74 buildings, or 17% of the total).

Shanghai unveiled 13 new venues, the highest number in any city. The Shanghai Grand Theatre, completed in 1998, is one of dozens of state-backed performing arts complexes that have sprung up in China’s fast-growing cities in recent decades. Thanks in part to the vast scale of these “grand theatres”, which usually combine an opera house, a concert hall and a theatre under one roof, Asia boasts the top-ten largest arts venues in the study. By contrast, the average floor space of new cultural buildings in North America has increasingly reduced in the years since 2010.

There are practical and political reasons behind Asia’s bigger-is-better approach. Urban land is owned by the state in China and elsewhere, turbocharging development. And the researchers point to authoritarian governments’ quest for “soft power and regime legitimation” as another motive behind mega-structures such as the Zaha Hadid-designed Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku, Azerbaijan and the Louvre Abu Dhabi—the product of a bilateral deal between France and the UAE.

Asia’s rise may explain a surprising trend in the data: while investment in major cultural buildings has soared (the 2010s projects cost $52.2bn overall, almost five times the 1990s spend of $10.6bn), the average project cost has declined. Gogishvili cites the state ownership of land, cheaper labour costs and China’s turn towards more local architects as possible contributing factors.

Playing catch-up

The “unparalleled” construction boom in China looks set to continue through the 2020s, the researchers say, with Shenzhen alone planning at least ten museums and cultural buildings worth an estimated $3bn. Meanwhile, the Gulf states are only getting started, eager to leverage culture to expand their international influence and diversify their oil-based economies. Though the study records that just 14 major arts venues opened in the region between 1990 and 2019, a raft of new projects is

anticipated to reach completion in the UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia by the end of this decade.

But it may be too soon to proclaim this global explosion of capital investment as a shift in the axis of culture. Adrian Ellis, the director of the cultural strategy firm AEA Consulting, which provided data to the University of Lausanne team, says that the Asian and Middle Eastern cities intent on building big today are still “in catch-up”. “It will be decades before they reach the sheer number and depth of public museums and performing arts venues in cities like London, Rome or Paris,” Ellis says.

What is more, the trend of building grand palaces of culture as tourism magnets and status symbols appears “curiously detached” from the current drive in the cultural sector towards greater accessibility and community engagement, Ellis says. It is also, of course, “insensitive to the biggest issue in the world”—climate change—begging a pointed question for planners, policymakers and cultural leaders everywhere: “Are we going to see, and at what pace are we going to see, a change in the architectural agenda?”