The emblem of Islanders: The Making of the Mediterranean, a major exhibition opening at the Fitzwilliam Museum, is a bronze boat made in Sardinia almost 3,000 years ago. The vessel has a splendid horned animal for a prow, birds perched around the rigging, and a mast believed to represent the island’s distinctive prehistoric stone towers—built by the now vanished Nuragic culture, whose people had no writing and so left only their works to tell their story. The boat stands for the curators’ belief that the sea united rather than divided the Mediterranean island cultures, constantly renewing them with materials, skills, fashions, legends and people—sometimes arriving as conquering armies, more often as traders and settlers.

The curators believe that the sea united rather than divided the Mediterranean island cultures

The Fitzwilliam director Luke Syson writes in his catalogue introduction that the island character is essentially hybrid, “an identity of accretion”. He notes that the words “insularity” and “isolation” both come from the Latin for “island” but argues that, although the sea made the islands particularly vulnerable to invasion, it also resulted in a culture “as much from the welcoming of foreigners as from any enduring invasion”.

Many of the 200 objects in the exhibition, including splendid loans, represent stories islanders told to explain their tangled histories. Cyprus, the birthplace of Aphrodite, sends a statue from Nicosia’s archaeological museum (Cyprus Museum) of the goddess rising from the sea, head and feet lost but none of her beauty, an image that greatly influenced the work of Renaissance artists, including Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1485). From Sardinia, whose stone towers were later explained as the homes of witches or giants, the people who built them will be seen in vivid little bronze votive figures of warriors and archers, including a touching representation of a woman and child, interpreted by the curators as a mother mourning the dead child she holds. The bronzes are coming to the UK for the first time, on loan from the National Archaeological Museum of Cagliari.

A beautifully preserved horse-drawn chariot and rider (750-600BC) from Agia Eirini © Cyprus Department of Antiquities

Crete, the home of King Minos and the fearsome Minotaur—the show steers clear of Knossos, the subject of an overlapping major exhibition at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum—is the source of a drawing of a dolphin scratched onto a scrap of limestone, an image of a sacred fish that also represented friendship, whose author was proud enough to sign in Greek “…made me” only for his name to be lost on the broken stone.

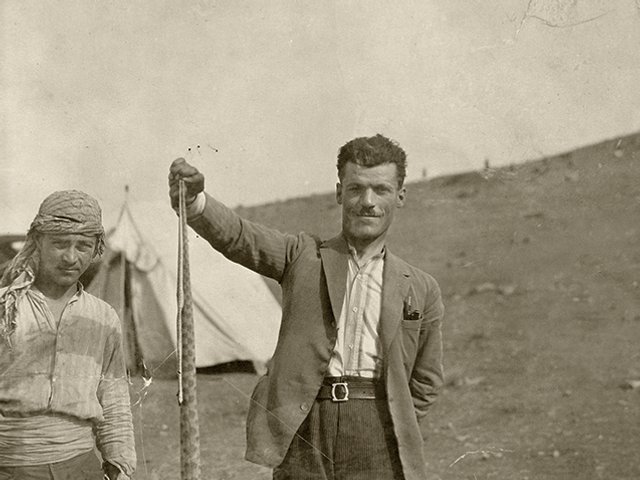

The Cyprus Museum is also sending to the UK for the first time some of the extraordinary clay figures from Agia Eirini, a site in north-west Cyprus excavated after a chance find in 1929. The Swedish archaeological team there found more than 2,000 figures grouped in a semicircle around an altar, neatly arranged in size from miniature animals, chariots and humans to larger-than-life-size warriors.

It was inevitably dubbed “the Cypriot terracotta army” and is now divided between the island museum and Stockholm’s Medelhavsmuseet. Many seem to have been made by the same workshop, and some appear to be portraits—the faces of islanders staring back at us from more than 2,600 years ago.

• Islanders: The Making of the Mediterranean, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 24 February-4 June