The sixth edition of the Dhaka Art Summit (DAS) opened last week (until 11 February) to the lively extremes one might expect when a select group of art world elites parachute into a festival held in the world’s most densely populated city.

DAS, which is free to attend, underscores its egalitarian aims by not having a VIP preview, meaning that star curators and prominent gallerists jostled among local students, state officials, office workers and cultural enthusiasts, to see a show that brings together more than 160 artists from Bangladesh, South Asia and further afield.

They were welcomed by the event’s founders, the Dhaka collector power couple Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani, and the summit’s chief curator Diana Campbell, who, aided by a network of collaborators and strong ties to the government, have staged a show that platforms the country’s historically under-represented art scene while addressing issues such as the climate crisis and gender through a local lens.

With a run time considerably shorter than other major art exhibitions it is unlikely that most of our readers will make it to DAS 2023—so here are seven talking points that were discussed among its attendees.

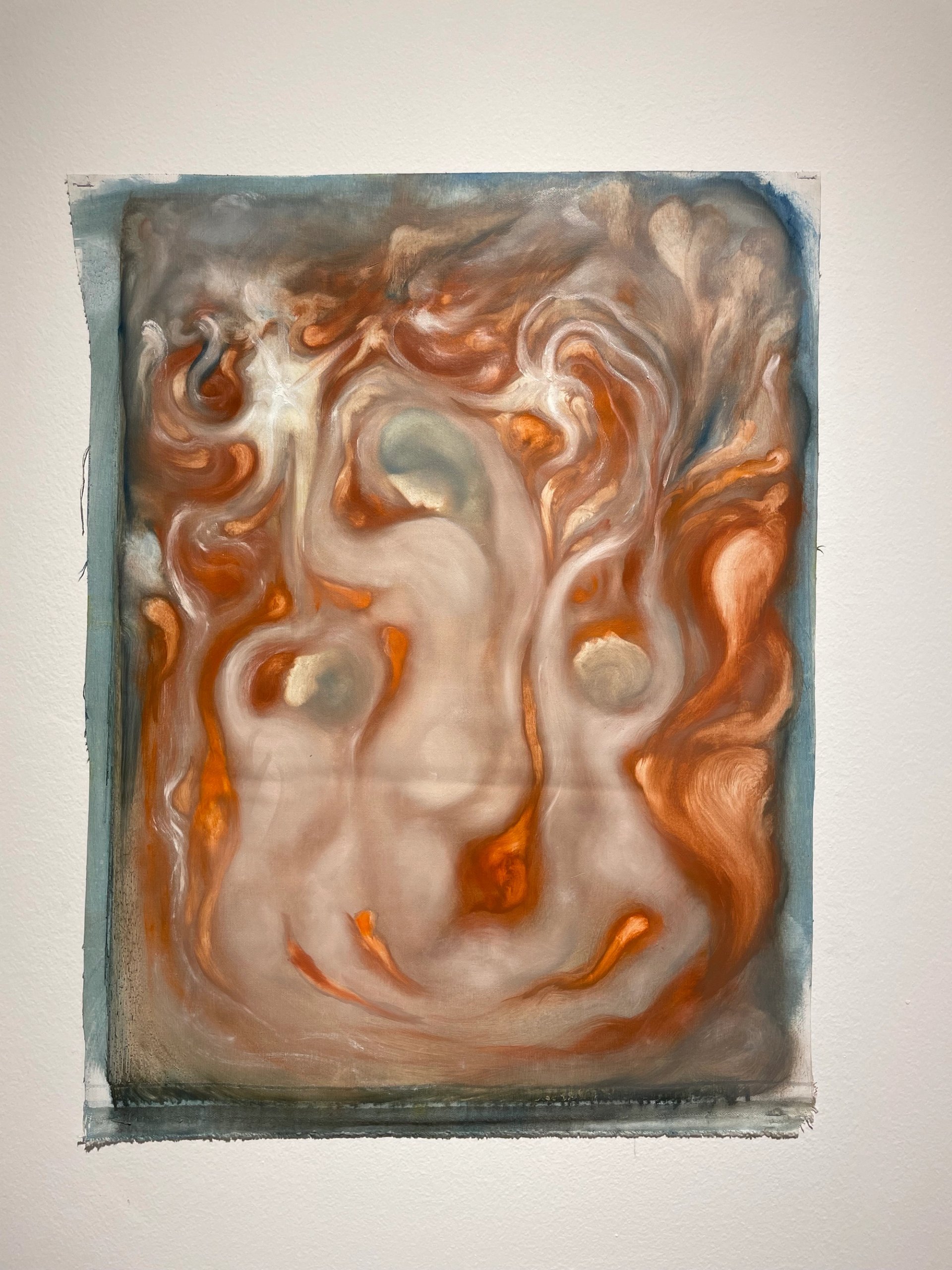

Bhasha Chakrabarti's Tender Transgressions (2022-2023) at DAS 2023

Photo Shadman Sakib, Copyright DAS 2023

To-the-wire hang

Like any exhibition venue, the government-owned Shilpakala Academy, where the summit is regularly held, presents its own challenges. Among the curveballs thrown at DAS organisers this year was a ten-day delay in accessing the building because the Asia Art Biennale in Bangladesh—the continent’s oldest art biennial—extended its run time. “Events were also held in the venue’s auditorium during our installation and sound-based works weren’t able to be rehearsed for four of the installation days,” Campbell says.

Adding to this stress, a two-day customs strike on 29 and 30 January in Bangladesh meant that some of the show’s works were only delivered 48 hours before opening. Indeed, a number of artists were installing until the early morning, including the Connecticut-based Bhasha Chakrabati, whose towering textile and plant installations were being braided together some four hours before the crowds arrived, she says. But by the time the first visitors came in, the exhibition was ready and appeared—especially in comparison to other recently staged South Asian exhibitions—remarkably professional.

Miet Warlop's performance Chant for Hope at Dhaka Art Summit 2023

Photo: Kabir Jhala

The performance of language

The theme of DAS 2023 is “Bonna”, the Bangla word for “flood” as well as a name commonly given to girls (the first time a Bangla word has been used for the summit’s theme). Behind this choice is the desire for viewers to rethink their outlooks on certain words and phrases—for example, heavy rains in Bangladesh are not seen as a disaster, but a way of life—so as to learn from communities who have adapted to extreme weather for generations. Language is a long-standing curatorial concern of Campbell—who emphatically maintains that the once-in-every-two-years DAS is not a “biennial”—and she reminded attendees at the opening conference that “words are important”.

Fittingly then, kicking off the summit’s packed performance programme was a work by the Belgian musician Miet Warlop, for which a group of Bangladeshi dancers and actors moved to an intense percussive soundtrack while creating and disseminating clay tiles imprinted with letters in Bangla. The energetic work spoke to the formation and resilience of the region’s language: Bangladesh’s Language Movement was pivotal to it gaining its independence from West Pakistan in 1971.

Ahmet Öğüt, Jump Up! (2022)

Photo Shadman Sakib © DAS 2023

Releasing one’s inner child

The perspectives of children are central to the DAS exhibition Very Small Feelings, co-curated by Campbell and Akansha Rastogi, a senior curator at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in Delhi, and, incidentally, a new mother herself. Works in this crowd-favourite show include Matthew Krishanu’s tender paintings of himself and his brother as young boys, and Afrah Shafiq’s interactive work based on Soviet video games which were popular among India’s youth in the 1980s.

This curatorial concept was no more apparent, nor executed quite as charmingly, than in an installation work by the artist Ahmet Öğüt made in response to a suite of colourful abstract paintings by the legendary Indian pedagogue and artist Benode Behari Mukherjee—the father of the late Mrinalini Mukherjee and the husband of Leela Mukherjee, whose works also appear in the show. His works are hung well above the eye level of the average adult in order to simulate how many children navigate exhibitions. Luckily, underneath each work, Öğüt has placed a small trampoline, encouraging viewers of all ages to jump up and down to more closely inspect them, and equally importantly, to let down their guards and access their inner child.

Antony Gormley's Turn (2023) at Dhaka Art Summit 2023

© DAS

Gormley’s gap year

One of the show’s most disarming works is also by arguably its most famous (and certainly most expensive) artist. “I think it’s by Asim Waqif,” said one observer approaching a series of vast bamboo circles which skirt the room’s ceiling and extend out of its open windows. But upon consulting the wall text, many viewers were surprised to learn it was a new work from the British sculptor Antony Gormley’s Clearing series.

For the work, which is Gormley’s first using bamboo, the artist spent a week with six craftsmen from a village 80 km to the west of Dhaka to execute something formally similar to the single coiling line aluminium that has graced New York’s Brooklyn Bridge Park, but wholly different in the mood it intends to project.

“Previously, all the Clearings have had a kind of manic energy,” Gormley tells The Art Newspaper. “But with this more organic material we were able to give the work clarity and a kind of lyrical looping speed that contrasted with the vertical and horizontal lines of the building's architecture. I was very pleased when I saw people, particularly children, running, ducking, diving and jumping through it. I hope that it conveys joy in the fluid flexibility of both this amazing form of grass and the bodies that pass through it.”

This marks Gormley’s return to South Asia after almost 50 years, when he backpacked through the subcontinent during an extended gap year. The sculptor says of his time in the country: “I arrived in India in 1972, having spent a year on the road getting there and I lived in various places in Dalhousie and Darjeeling in the Himalayas, and various times in Rajasthan, Bihar, Tamil Nadu, Bengal and Orissa... I did nine-, ten-day silent meditation courses with S. N. Goenka in that time, whilst also practising daily meditation.”

Sana Shahmuradova-Tanska's The Womb of the Land (2022)

Visual reports from Ukraine

Many of the paintings in the show are sequestered into a single room, which is the only one that can be fully locked and climate controlled, Campbell explains. In pride of place is a wall of work by two female Ukrainian artists made in the last 12 months. Of these, two by the artist Sana Shahmuradova-Tanska were shipped by truck from Kyiv and then by train to Warsaw, where they were then collected by the Polish curator and frequent DAS collaborator Sebastian Cichocki, and brought to the summit rolled up in his checked luggage.

"I was so afraid they would get lost in transit, especially when I couldn’t initially see my suitcase in baggage claim,” Cichocki says. He adds that these works have all been executed rapidly and function very much as “reportage” from the crisis. Shahmuradova-Tanska, he explains, uploads her work quickly to Instagram so her art can serve as a window into the crisis. These works were all acquired by the Samdanis, with the proceeds of one painting going to charities in Ukraine, Campbell says.

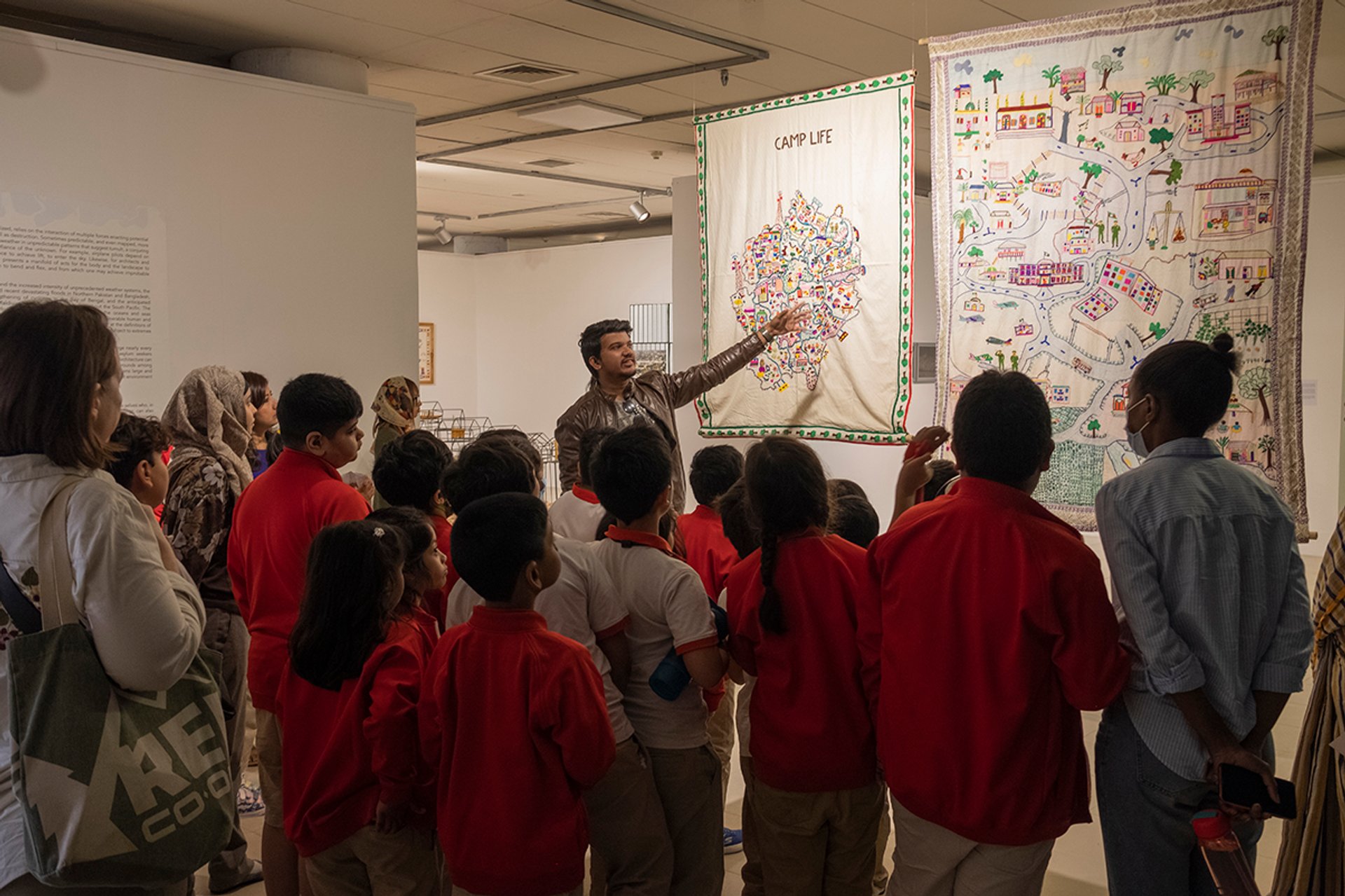

Rohingya Cultural Memory Centre (RCMC) © Dhaka Art Summit 2023

Platform for Rohingyas

Of course, conflicts are not limited to Ukraine— even if the art world’s charitable focus appears to be. “Without wishing to diminish the severity of the war in Ukraine, it is one of several violent conflicts taking place around the world, and that we want to shine a light on,” Campbell says. Accordingly, DAS 2023 also serves as a platform for an issue much closer to Bangladesh’s borders: the Rohingya refugee crisis. With more than 500,000 displaced Rohingya people living in the Kutupalong refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, three separate rooms play host to works by, or addressing, those affected by the crisis.

Many works come from the Rohingya Cultural Memory Centre, such as hand-embroidered tapestries woven by Rohingya artisans that depict their present life, aspirations and stories from their oral culture. Works of art by some of the displaced people are also displayed upstairs in the summit’s shop, but are crucially not for sale. “As much as they might need funds, it is also important to allow these communities the space and freedom to make art rather than crafts to be sold,” a shop assistant says.

Miet Warlop's The Board II, 2014, (2023). Photo Shadman Sakib, Copyright Dhaka Art Summit 2023

The Dhaka-umenta effect?

A number of attendees were overheard comparing DAS 2023 to the most recent edition of Documenta for its focus on play, attempts to disarm austere exhibition spaces and foster an atmosphere more akin to a music festival than a museum show. But, as Campbell points out, the Indonesian collective ruangrupa served as advisers to the last DAS before they were announced as the curators of Documenta 15, and several other key artists from the Kassel show were shown in Dhaka beforehand, including Jatiwangi Art Factory, where they were first introduced to global art audiences.

“We play together and we think together,” Campbell says of the “overlap” between her and ruangrupa’s projects. “Both of us work very openly, we are not trying to safeguard knowledge.” Speaking of her main sources of inspiration for DAS 2023, Campbell says she went to lots of music festivals to see “how young people gather” and also studied local village theatre traditions across the world. Yet this is not to say she has not been influenced by ruangrupa. “If there is anything I have learned from their philosophy it is to ‘make friends not art’. This is a tough show to pull off and the kinds of loans and logistics required to do so only happen because people go out of their way to make it happen.”