Mainland China’s nationwide protests in late November have taken on a worldwide resonance, encapsulated in the simple image of a blank, white sheet of A4 paper. Held aloft by protesters or attached to street signs and statues, the blank paper has become a visual icon, mutely conveying the frustrations and hopes that must be restrained and expunged under repressive regimes and censorship.

“The blank paper speaks for the speechless,” says a China-based curator, preferring to remain anonymous for safety reasons. “I think the white paper’s efficacy lies in its lack of explicit meaning, how a paper without words is itself a medium of resistance and a recognisable code.”

The blank sheet “obviously has an existential meaning”, says the pioneering Chinese artist Xiao Lu, whose 1989 piece, Dialogue, is considered the “shot that started Tiananmen” and who has been engaging in searing political performance art and photography ever since, though she now resides abroad. The use of blank paper dates back decades, resurfacing most recently in the hands of Russian anti-war protesters. Last month, she says, after “first being wielded at the Nanjing Institute of Communication in China, the papers were popularised nationwide and have spread to diaspora Chinese protests around the world”.

Physiological necessity

“I think that the white-paper revolution appeared almost spontaneously as a physiological necessity,” says the curator, “because freedom is a human need, no less than breathing.” Xiao sees in the blank paper echoes of Abstract Minimalist Robert Ryman’s 1960s series of untitled white paintings. In 2016, the Philippines artist and activist Kiri Dalena created Erased Slogans, a series of photographs of protests in the 1970s with their words blanked out. Such white abstract works had a burst of popularity on WeChat Moments during the protests, as some in the art world covertly signalled their support through such art-historical imagery.

Among the known figures of the anonymous November protests is an artist and instructor who goes by the name of Teacher Li, now living overseas and able to prolifically share videos, images and stories from China to the outside world via Twitter. “The [blank] paper started not from an artistic point of view but from a very practical perspective about freedom of speech,” he says. “As you know, in China we can’t speak out, we can’t express anything. Any radical writing has to use abbreviations, so in the end people chose blankness. Painting often starts with a blank piece of paper, so although we can’t see it with the naked eye, it exists in every painting—and, one day, the unseen characters on the white paper will become clearer and clearer.”

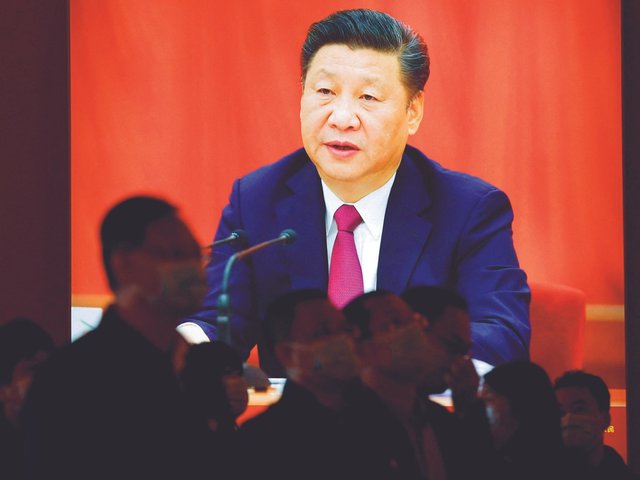

The white-paper protests initially erupted after a fire on 24 November that killed at least ten people in Urumqi, which, like most of the Xinjiang region, had been under strict lockdown for over 100 days. Rescue services are believed to have been hampered by the lockdown barricades. The next night, thousands protested in Urumqi, followed by protests in Shanghai then Beijing and dozens more cities. While mourning Urumqi’s and other needless deaths and calling for an end to Covid restrictions, the protest swelled into calls for artistic and cultural freedom, and even for the Communist Party and its leader Xi Jinping to step down.

On 26 November, hundreds of mostly young Shanghai residents gathered at Middle Wulumuqi—Mandarin for Urumqi—Road. The neighbourhood is one of Shanghai’s main art districts, with more than a dozen galleries and non-profits plus a major theatre and design shops crammed into a few picturesque blocks. They placed flowers, candles and white papers on and around the Wulumuqi street sign—which itself became iconic after authorities removed it the following night, only to sheepishly replace it a few hours later after resounding online derision.

Removed by police from the initial location, protesters rebuilt memorial shrines on pavements, benches and public lavatories. Similar scenes played out all over the country.

Online, art poured out in support. A simple drawing of hands holding up blank paper joined ensuing political cartoons skewering the street-sign removal and the chaotic sudden pivot to lifting Covid-19 restrictions. One statue was so covered in papers—some blank, some with calligraphy declaring “Freedom”—that it resembled a Covid-enforcing white hazmat-suited dabai. Overseas protests, largely by students of Chinese origin, have continued. A student at University of California Los Angeles covered herself in white papers as another dressed as a dabai sprayed red water on herself until the sheets were dripping, like blood.

Directness becomes avant-garde

“Today’s China is so complex that it requires a lot of explanation to the outside, and the original avant-garde language may not be avant-garde enough at this time”, says the curator. “Therefore, relatively direct methods, such as design and performance, prove more effective—and directness and effectiveness have temporarily become avant-garde language.”

Wulumuqi Road is now jammed with police and dilapidated barricades, clearly repurposed from Shanghai’s spring lockdown or street construction. Handbills hastily pulled from their sides produce square outlines or white blocks, themselves an unintended protest. White papers are now showing up as solidarity with China and at protests in Iran and Russia.

The Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei, who was initially dismissive of the protests, made a surprise appearance at Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park, London, in the run up to Christmas, sporting a Father Christmas hat and selling white sheets to fundraise for refugees. The curator welcomes Ai’s white-paper moment: “Ai’s a big shot and whatever he does makes noise. The current resistance is not loud enough; any amplification helps the world recognise the importance of a future where the Chinese people are pursuing political reform.”

The front page of our January 2023 issue carries a blank image, reflecting how the use of blank paper has become "a medium of resistance and a recognisable code", says a China-based curator