The National Gallery broke off a collaboration with Moscow’s Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, The Art Newspaper can reveal. Although it was never publicised, the two institutions were to have jointly presented next year’s exhibition After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art, but the arrangement was abruptly terminated following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Loans from the Pushkin have been withdrawn and there will now be only one showing—in London.

In early March, just over a week after Russian forces marched into Ukraine, Gabriele Finaldi, the National Gallery director, made the difficult decision to phone his Pushkin counterpart, Marina Loshak, with a clear message: it’s off.

Bigger plans

The idea for After Impressionism, an exhibition on the beginnings of Modern art, came from the National Gallery, but it was transformed after a visit to London by Loshak in February 2020, a month before the Covid lockdown.

The plan was an ambitious one. The show would focus on the period from 1886 (the final Impressionist exhibition) to 1914 (the start of the First World War), covering developments from Post-Impressionism to Fauvism, Cubism and abstraction. Christopher Riopelle, the National Gallery’s 19th-century curator, told us: “We immediately jumped at the idea of collaborating with the Pushkin.”

Loshak had taken over as the Pushkin’s director in 2013 from Irina Antonova, then 91, who had joined the museum back in 1945. During the Cold War and its aftermath, the Pushkin was isolated from the museum world, but Loshak has been determined to develop its international links. After Impressionism was a key element of her strategy.

As discussions evolved, the Pushkin agreed to provide ten major paintings and sculptures and help secure another five from the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, mainly works once assembled by Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, two of the world’s greatest early collectors of French Modern art. The artists who were to be featured in After Impressionism included Gauguin, Van Gogh, Rodin, Degas, Munch, Klimt, Derain, Maillol and Mondrian.

In return, the National Gallery would provide five paintings, including Cézanne’s majestic Bathers (1894-1905), and help arrange dozens of further loans from international museums and private collections. Altogether After Impressionism was to include about 80 paintings and 20 sculptures.

The show was scheduled to open at the National Gallery (25 March-13 August 2023) and then move to the Pushkin (October 2023-January 2024). In London it would be co-curated by Riopelle and independent specialist MaryAnne Stevens. Because of Covid restrictions, neither of them actually got to Moscow, so discussions were largely by email.

With the invasion of Ukraine on 24 February, cultural relations between Russia and the West came to an abrupt halt. Economic sanctions were quickly introduced by the West. Air links were severed. Art works then on international loan for exhibitions in Russia and the West were at risk, with some Russian loans to Italy temporarily seized in Finland on their return journey.

Finaldi made an immediate decision to sever collaboration with the Pushkin. He was also determined to go ahead with the London presentation without Russian loans for the planned March 2023 opening date. This meant modifying the exhibition and seeking alternative works at short notice.

Ins and outs: the show has replaced Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire (1906) from the Pushkin (right) with the artist’s Mont Sainte-Victoire (1902-04) from the Philadelphia Museum of Art (left)

The famous six becomes five

After Impressionism originally focused on how avant-garde artists in six European cities forged the beginnings of Modern art: in Paris (most importantly), Barcelona, Berlin, Brussels, Vienna and Moscow. Following the invasion of Ukraine, Moscow as a key city in the show was dropped, since the significant works would have had to come from Russia.

The National Gallery then faced the daunting task of quickly finding replacements for the 15 loans—some of the greatest Modern works—that had been promised from Russia.

Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire (1906), bought by Shchukin a year after it was painted (and now at the Pushkin), was replaced with a similar landscape (1902-04) which has now been promised by the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

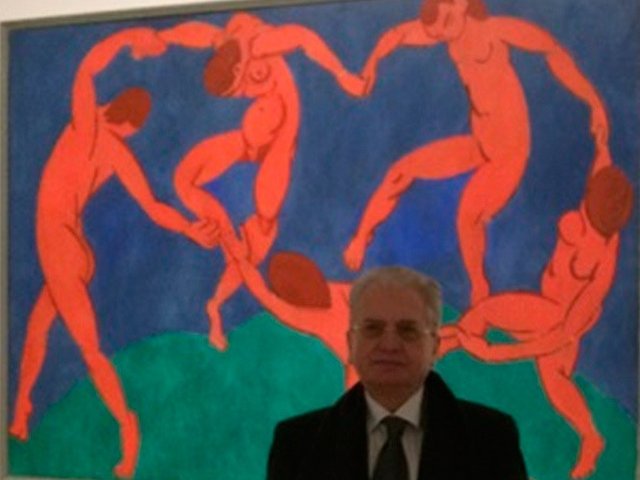

A replacement for Wassily Kandinsky’s key work Abstraction 20 (1911) is to be borrowed from a private collection. Another private collector has agreed to lend Picasso’s Portrait of Wilhelm Uhde (1910) instead of the Cubist Portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1910). Alternatives are now being finalised for two other masterpieces in Moscow: Henri Matisse’s The Pink Studio (1911) and Edvard Munch’s White Night (1902-03).

Stevens, who has been travelling to discuss potential replacements with lenders for much of this year, found “incredible receptiveness” from both international museums and private collectors. It has been “heartwarming”, she says, with everyone trying to help deal with a problem created by the invasion of Ukraine. Sadly, it now looks like it will take many years to re-establish museum relations between Russia and the West.