Didier William’s current retrospective is, more so than most, an origin story. The artist’s family emigrated from Port-au-Prince in Haiti to North Miami when he was a child, and he grew up in two houses near the present site of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) North Miami, which is hosting the show curated by Erica Moiah James (until 16 April 2023). Two of the most recent works on view are paintings of those childhood homes, each floating uneasily on a conglomeration of limbs rendered in William’s distinctive, densely rendered brushstrokes.

In another real sense, the exhibition—and William’s work more broadly—is about the fluidity and hybridity of identity and experiences of dislocation, as intimated by its title, Nou Kite Tout Sa Dèyè, Haitian Creole for “We’ve Left That All Behind”. William discusses the experience of returning to the neighbourhood of his youth, taking stock of his oeuvre up to this point and his first foray into large-scale sculpture.

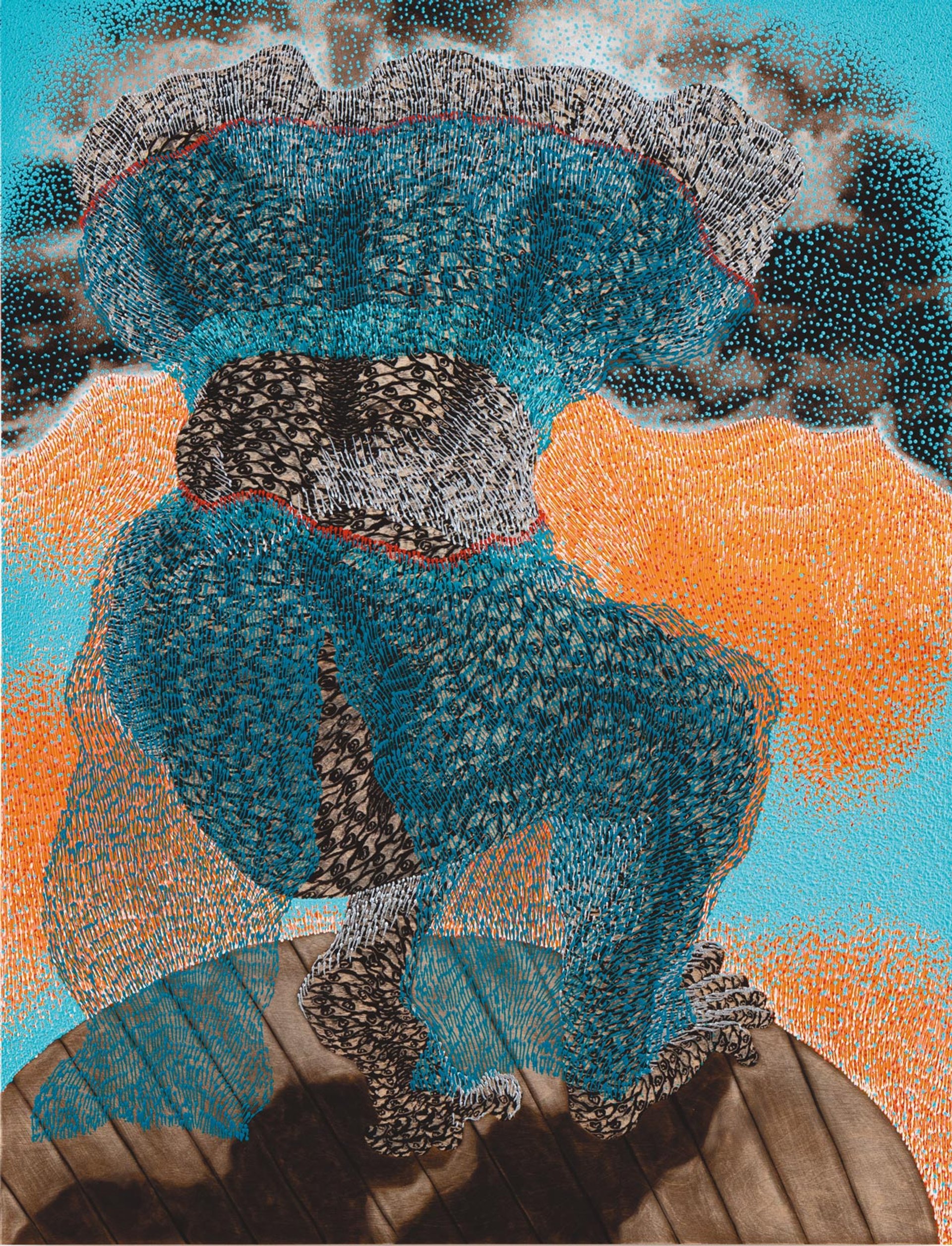

Didier William’s Mosaic Pool, Miami (2021) is on show at MOCA North Miami in an exhibition of more than 40 works Photo: Constance Mensh, courtesy of the collection of Reginald and Aliya Browne

The Art Newspaper: Can you tell me how the large sculpture you’re debuting in North Miami came about?

Didier William: Last year I did a site-specific installation for Facebook in New York and that was the first time I had done anything 3D. It was a 72ft by 15ft wall, with six of my figures floating in front of it, and the figures had been cut out—so imagine if the figures in my paintings had stepped out of the paintings. On the wall was a custom-printed wallpaper with patterns that had been pulled from the paintings, and then I collaborated with a lighting manufacturer who made LEDs to light the backs of the figures so that instead of casting a shadow, they emitted light from behind them.

Erica Moiah James saw that piece at Facebook, really loved it and asked me to consider a sculpture for Miami. So the show in Miami has a 13ft-tall stack of bodies that hovers in the middle of the room. Its title is Potomitan, which means the pole in the middle of a structure, which is borrowed from Haitian Vodou. In Haitian Vodou, you would pray and have ceremonies around the potomitan, which would sometimes be an actual living tree. Sometimes it’s a wooden structure that you would build and put different worship objects around. That pole is where the gods travel from the other world into this world. But in my piece that pole, that structure, is made up of bodies, a towering stack of bodies, the bodies themselves being the throughway or transitory material through which we access life in this world and life in the next world.

The first works visitors to the exhibition see are two paintings of your childhood homes in North Miami; why did you choose to represent such tangible, real-world places?

They are containers. When we first moved to this country, we weren’t documented, so we had a long, several-years process of going to immigration and naturalisation services, setting up appointments, getting job permits, getting a green card, becoming American citizens, my brothers and I learning English. My parents tried to find jobs, and tried to find schools for us. I take a lot of that anecdotal material that comes from those moments and find the slice in there that I think can become a painting. But the container for all that stuff was these two houses, all of that activity was happening in these two-bedroom, one-bathroom houses where my brothers and my parents were desperately trying to start a life in the United States.

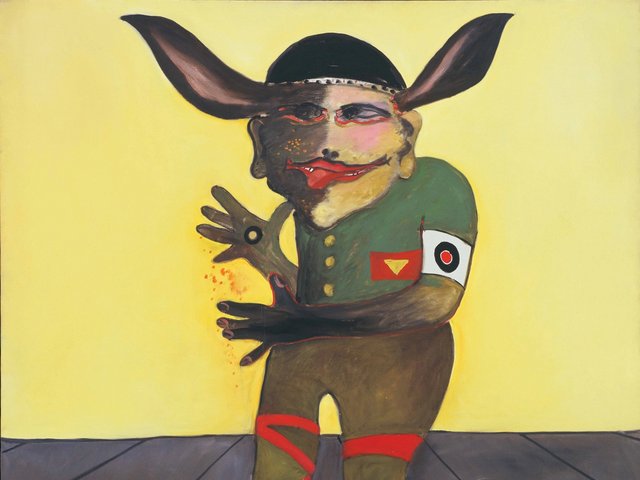

William’s Gwo Madame (2020) Courtesy of the Braiteh Foundation Collection

More broadly, what has the experience of reinvesting in this place where you spent such important years of your life brought up for you?

I like how you describe it as a kind of reinvestment. The museum likes to use the word “homecoming” and I don’t because I think homecoming implies some kind of resolution or catharsis, and I’m not crazy about that implication. I think of it more as an introduction or a reintroduction. The Miami that I grew up in is very different from the Miami that exists today. And the 16-year-old kid who worked at the dollar store on 125th Street, which is right next door to the museum, is not the same person as the 39-year-old, out, queer dad who’s returning to Miami to show this work.

The Miami that I grew up in is very different from the Miami that exists today

I want to give those two parts of self their deserved integrity, and not assume that we’re “closing the circle” and “bringing the work back home”. Because that image also implies that somehow the conception of home is fixed and, again, within the context of an immigrant narrative, home is never a fixed institution—it’s a kind of organic, shifting, multivalent thing that you can never really quite latch onto. That’s how I’ve always experienced it as a person in the world, but also how I’ve always constructed it in the narratives of the paintings. So one of the things I think about a lot with bringing the work back to Miami is language, the power of language and how the language that I use to describe the paintings—the art historical language, the Creole language, the material language—is gonna be very different in Miami, in a community that has a large immigrant population and a large Haitian population. The symbolism and the storytelling will play out very differently and I’m excited to see what happens.

• Didier William: Nou Kite Tout Sa Dèyè, Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami, until 16 April 2023