“It isn’t a given that museums will take whatever you have to donate,” says Michael Duffy, national head of art and collectibles planning in the private banking division of Bank of America, “even if what you have are interesting pieces by important artists. Collectors shouldn’t mistake their local museum for [the charity] Goodwill.”

If you are a collector with estate planning on your mind or an heir to a collection of art, antiques or other valuable objects, the tax-saving idea of donating works to a museum may not be as easy as you hoped. Duffy says most museums—particularly the largest and most prestigious institutions—reject the vast majority of proposed donations.

“If you own a major work by a major artist, it is pretty easy to find a home in a museum for it,” says Doug Woodham, a New York-based art adviser who works with collectors seeking to donate some or all of their holdings to museums or other non-profit institutions. “Everything else can be problematic.”

There are many reasons a museum might refuse a work. The piece being offered may not be in line with the institution’s mission—a museum devoted to contemporary art would have no use for an Impressionist painting, regardless of its quality and importance. Even if the institution does collect and display art consistent with what a prospective donor is offering, it may still reject the gift if it already has one or more pieces just like the one being donated. In some cases, the objects on offer may not be in good condition—works in need of conservation say expense all over them.

Art collectors tend to think of their objects as assets whereas museums often view new additions to their collections as liabilitiesMichael Duffy, private banking division of Bank of America

Accessioning an object also costs institutions in terms of the time and manpower required for researching and cataloguing each item. Art collectors, Duffy says, tend to “think of their objects as assets”, whereas museums often view new additions to their collections “as liabilities”.

Finding a new home in a museum for a collection takes time and effort, which is something that can be done by collectors themselves—most successfully if they have a relationship with a particular institution as either a donor or board member—or by intermediaries. Candace Worth, an art adviser in Manhattan who says she doesn’t do much in the way of placing pieces in museums (“I will help out where I can, for long-time clients”), explains that commercial galleries are good sources of information about which institutions would be interested in a donation of a particular artist’s work. “That’s part of their job,” she says, adding that a growing number of galleries require the buyer of a work to donate another to a museum (the “buy one, gift one” strategy), frequently designating specific museums to receive the donation.

Galleries, however, may be more helpful in obtaining referrals to museums when the works to be donated are by contemporary artists or others whose markets are quite active, Woodham says. “With other artists, they don’t necessarily know which institutions would be interested. They are just as confused as the collectors.”

When turning down a collector’s offer of an object, museum curators might recommend another institution that could be interested, but Woodham says that scenario is unlikely as museums “are not in the business of getting works placed”. Museum curators, he says, are more apt to speak candidly with advisers about the reasons for rejecting a donation than with a collector whom “they don’t want to get on the wrong side of”.

Online donation broker

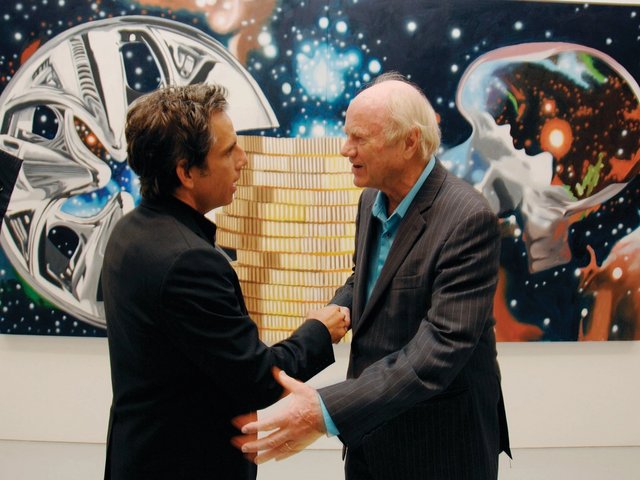

A newer service of interest here is the website Museum Exchange. Collectors can post on the platform descriptions and images of works they are seeking to donate for the consideration of museums, which, if interested, can then make a pitch to the collector. Objects up for donation are posted for three months, and Michael Darling, the site’s co-founder and chief growth officer, says his organisation assesses the provenance, attribution and condition of each piece, and ensures the owner has clear title to it. “We learn the approval process of each institution, and part of our job is to walk a collector through the process,” he says. “Our software package tracks the process.”

At present, Darling says, 178 museums around the US take part in this exchange. Those whose annual operating budgets are below $10m pay the organisation $1,000 for the service after a donation has been completed, while institutions with larger operating budgets pay $2,000. There are 340 collectors—who also pay $1,000 per object placed—“in the system”, Darling says, 116 of whom have put forward items for donation. Since the site launched in 2020, 376 donations have been completed.

Paying to donate is becoming standard procedure. Because museums look at gifted objects as liabilities, they regularly seek to offset their conservation, insurance, research and storage costs by asking for cash donations to accompany the object donations. “Many museums require a cash gift up to 10% of the appraised value of the material to offset expenses for accessioning the piece,” Duffy says.

Ego, he adds, will often lead a collector to want to see their pieces in a major museum with their name on a plaque on the wall. He recommends that collectors consider smaller, regional museums, university galleries, libraries and even hospitals, where the opportunities for tax deductions for charitable gifts are no less while their donations are more likely to be regularly on view and less likely to be rejected. Darling says 32% of Museum Exchange’s subscribing institutions are university museums.