In March, in the Jubilee Room of the UK’s Houses of Parliament, the British artist Wilma Woolf installed a series of white plates on a glass table. Each was inscribed with the names of the 1,425 women in the UK who, between 2009 and 2018, were murdered by men. Woolf also listed the cause of their death and their relationship to their murderer. “Several members of parliament were disbelieving and asked me to confirm they were real women,” Woolf says.

Many artists working in the UK, like Woolf, are creating significant and high-profile work on the subject of violence against women, yet leading institutions are failing to respond proportionately to the scale of the issue in exhibitions, programming and acquisitions.

“Museums have a responsibility to change this,” Woolf says. “They will have staff members and visitors who are both victims and perpetrators of this crime. As an employer, what are they doing? As an institution, how are they helping?”

Woolf’s work, called Domestic, was first shown last year at Richard Saltoun Gallery in London to mark the UN’s International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, which falls this year on 25 November. According to the Femicide Census, in the UK a woman dies at the hands of a man every three days. Home Office data reveals 400,000 women are sexually assaulted every year in England and Wales, while a survey commissioned by UN Women UK found that 97% of women aged 18-24 have experienced sexual harassment.

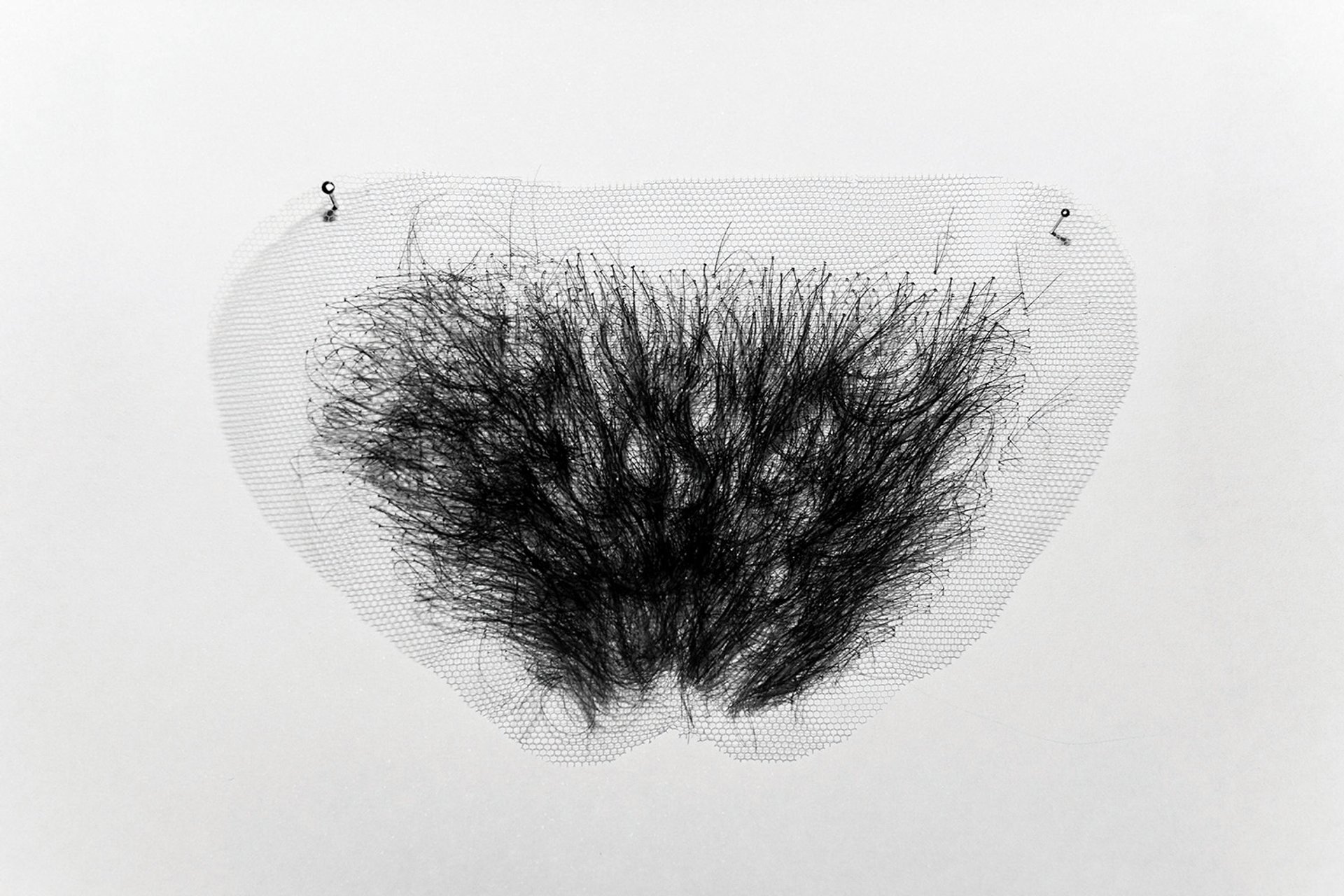

Laia Abril's Merkin (2019) © Laia Abril

The UK’s museum sector has confronted the issue of sexual violence against women, although examples remain scarce. They include Tate Modern’s 2020 retrospective of the visual activist Zanele Muholi, which includes Muholi’s photographic documentation of transgender women who have been abused and killed in South Africa. The Serpentine, meanwhile, recently presented Golden Lion recipient Sonia Boyce’s four-channel video installation, Yes, I Hear You (2022), as part of its Radio Ballads series.

“The murder of women is often talked about in the media as isolated incidents: one man losing momentary control. Artists can challenge that narrative,” Woolf says. “This is a conversation that needs to happen in all institutions across the UK, from museums to schools to hospitals to art galleries.”

The artist Poulomi Basu, a survivor of domestic abuse, has devoted her practice to telling the stories of women whose lives have been impacted by male violence, particularly in South Asia. Now based in the UK, Basu’s most recent work, Fireflies, was shown at Autograph gallery in London earlier this year. It remains the only UK institution to have staged a major exhibition on Basu to date. This may soon change, as Basu’s work has just been acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A).

Laia Abril's Mulier Taceat in Ecclesia (2019) © Laia Abril

Contemporary and circular

“The question is: do women have enough visibility, currently and historically, within UK institutions? Do women of colour have visibility within UK institutions?” Basu asks. “The answer to both is: no.”

Basu is one of a number of contemporary artists participating in the Parasol Foundation’s Women in Photography Project at the V&A, which launched last year. “These kinds of stories have been largely disregarded by the art canon and by cultural institutions,” says Fiona Rogers, the former chief operating officer at the Magnum Photos agency who was appointed as the foundation’s inaugural curator in March 2022. “Violence against women is not just historic,” she says. “Look at the recent murders of women by the Iranian state, or the overturn of Roe v. Wade in the US. It is a contemporary, circular issue. Why would UK institutions want to avoid debating this issues through art?”

Laia Abril's Shrinky Recipe (2019) © Laia Abril

This month, as part of the Parasol project, the V&A will open On Rape, a ‘chapter’ of the Spanish artist Laia Abril’s photographic series, A History of Misogyny. It is the first solo exhibition of Abril’s work to be held in the UK. But it will not be held within the museum; instead, it will be shown at the Copeland Gallery in Peckham, south London.

The series has been widely exhibited but, until now, has been ignored by UK institutions, Abril says. “We have to convince institutions to not be afraid of this work,” she says. “Because women’s rights are in jeopardy, continuously and everywhere.”

• A History of Misogyny, Chapter Two: On Rape and Institutional Failure, Laia Abril, until 27 November, Copeland Gallery, Peckham