Louise Lawler is a talker. Even, you might say, a bubbly one—except in interviews, a format she has resisted for years.

Her reticence owes nothing to shyness. Subversion is the name of her game. Using the tools of photography, an admirable civility and a sly wit, she upends the rules and conditions of display in galleries, museums, private homes and auction houses, exposing hidden bias in trusted norms and institutions. She keeps herself out of the picture, safe from the potentially harmful rays of celebrity. For Lawler, an artist is never more worthy of scrutiny than her art. She’ll welcome a conversation about that.

How about over lunch in the garden outside her studio in Brooklyn? She'll do the cooking—and ask the questions.

Installation view of Why Pictures Now 2017 at MoMA

They’re the same ones that Lawler proposes to herself when she goes to work. “What is work?” she begins, giving the pot of soup on her stove a pensive stir. This query is a close relative of Why Pictures Now, her 2017 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, where she printed and digitally stretched her previous photographs of famous works by Jeff Koons, Peter Halley and Takashi Murakami to create colossal grotesques on vinyl scaled to the walls. At this moment, she’s wondering how an image can become something more than an aesthetic composition of pictorial elements—something greater than itself or its maker. Something like an action affecting behaviour as well as perception.

Lawler’s essentially performative work of the past four decades—mainly installations of photographs and a variety of “souvenir” printed matter including matchbooks, posters and napkins—didn’t just poke the ribs of existing images in the manner of her Pictures Generation peers. Rather, through cropping, framing, lighting and other distorting manipulations available to her digital toolkit, she has shown us what happens to the value and the meaning of an artwork once it leaves an artist’s studio for new owners to place, store, sell, display, and sometimes claim for themselves. What’s an inquiring artist to do about it?

Lawler doesn’t ask that question, but she implies it in Not Enough to See, her exhibition for the domestically scaled Sprüth Magers outpost in Manhattan. As usual, her title is telling. How much visual information is needed to make the viewer aware not just of a social issue but also its environment? The same question attends the spectral pictures that Lawler shot of the Museum of Modern Art’s 2020 Donald Judd retrospective—with all of the lights turned off and no other living soul present. For this year's Venice Biennale, she hung those prints in a darkened space against stretched vinyls imprinted with enormous images of humping cats by Maurizio Cattelan.

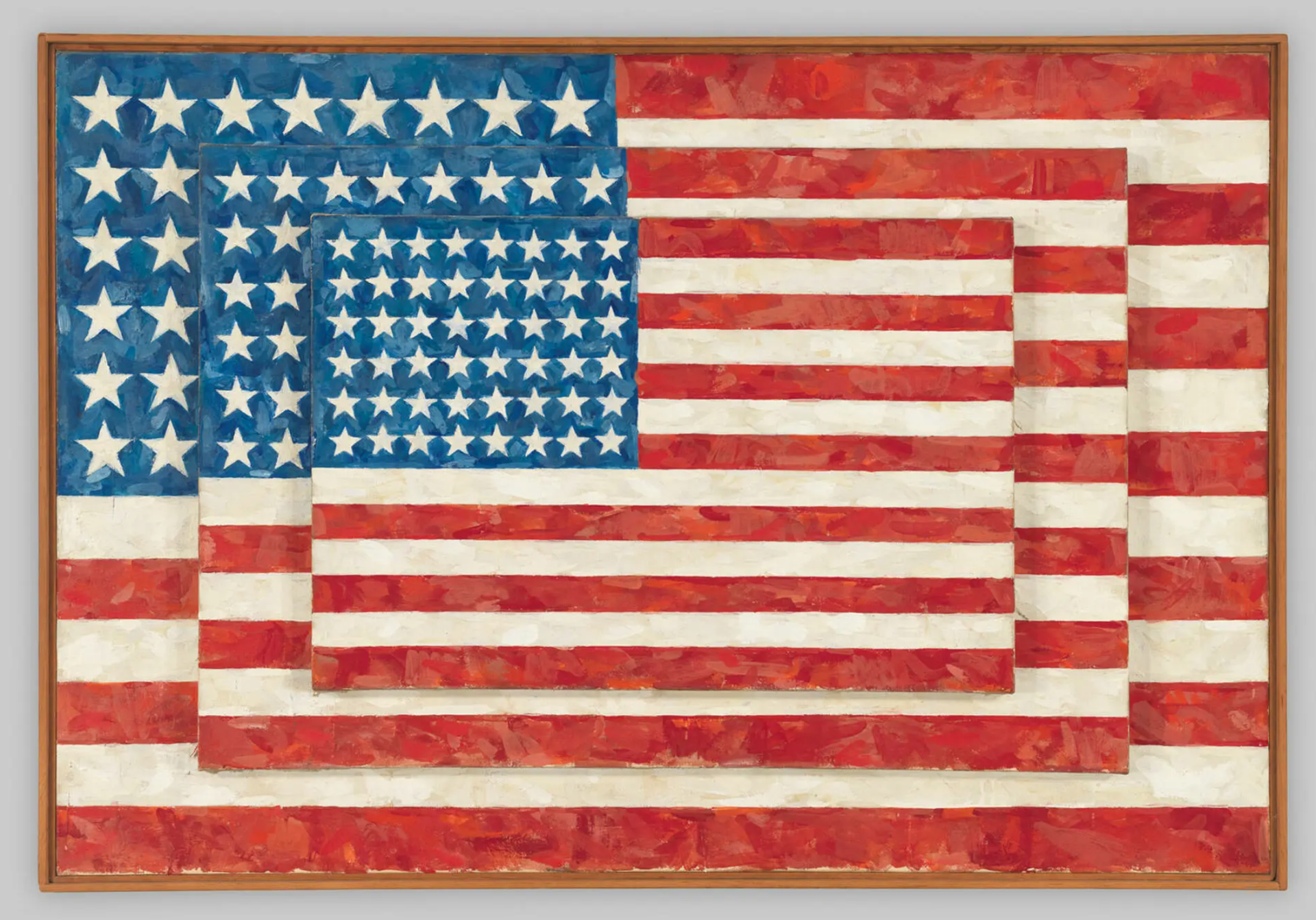

There’s no stretching in the half-dozen glossy panels at Sprüth Magers, where Lawler took a different approach, literally blurring the transformation of the American flag from a trusted symbol of democratic unity into the standard of rabid nationalists. The single example is Three Flags (1958) by Jasper Johns.

Three Flags (1958) by Jasper Johns.

Courtesy of the Whitney Museum

This painting has been on continuous view at the Whitney Museum since its 1980 purchase for a record $1m from the storied collectors Burton and Emily Tremaine. In 1984, they became the first to allow the young Lawler, whom they might have recognised at that time as the receptionist at the Leo Castelli Gallery, to photograph the masterpieces in their living room just the way they lived with them.

Her treatment was quite respectful, even fond. “I was totally touched by how attached the Tremaines were to the work and how they wanted to tell me about everything,” she recalls. “Emily literally said, ‘You’re going to love the Miró next to the thermostat!’”

Lawler shot Three Flags at the Whitney last year, when art handlers were taking down the museum’s Johns retrospective. She chose it deliberately and didn’t just snap her shutter. She moved the whole camera, as if “swiping” the image as we all do every day on our smartphones.

“Stretched” versions on vinyl will consume the gallery’s solo booth at the ADAA art fair (3-6 November). Lawler worries that the enlarged scale will make her blurred image look like a Gerhard Richter abstraction rather than a legible distortion of an action she took to address a symbol freighted with conflicted meaning. “Until you see it big, you don’t know how blown out it will look,” she notes. “You can’t test it.” Clearing the table, she allows: “It’ll be what it is.”

• Not Enough to See, Sprüth Magers New York, 3 November-23 December