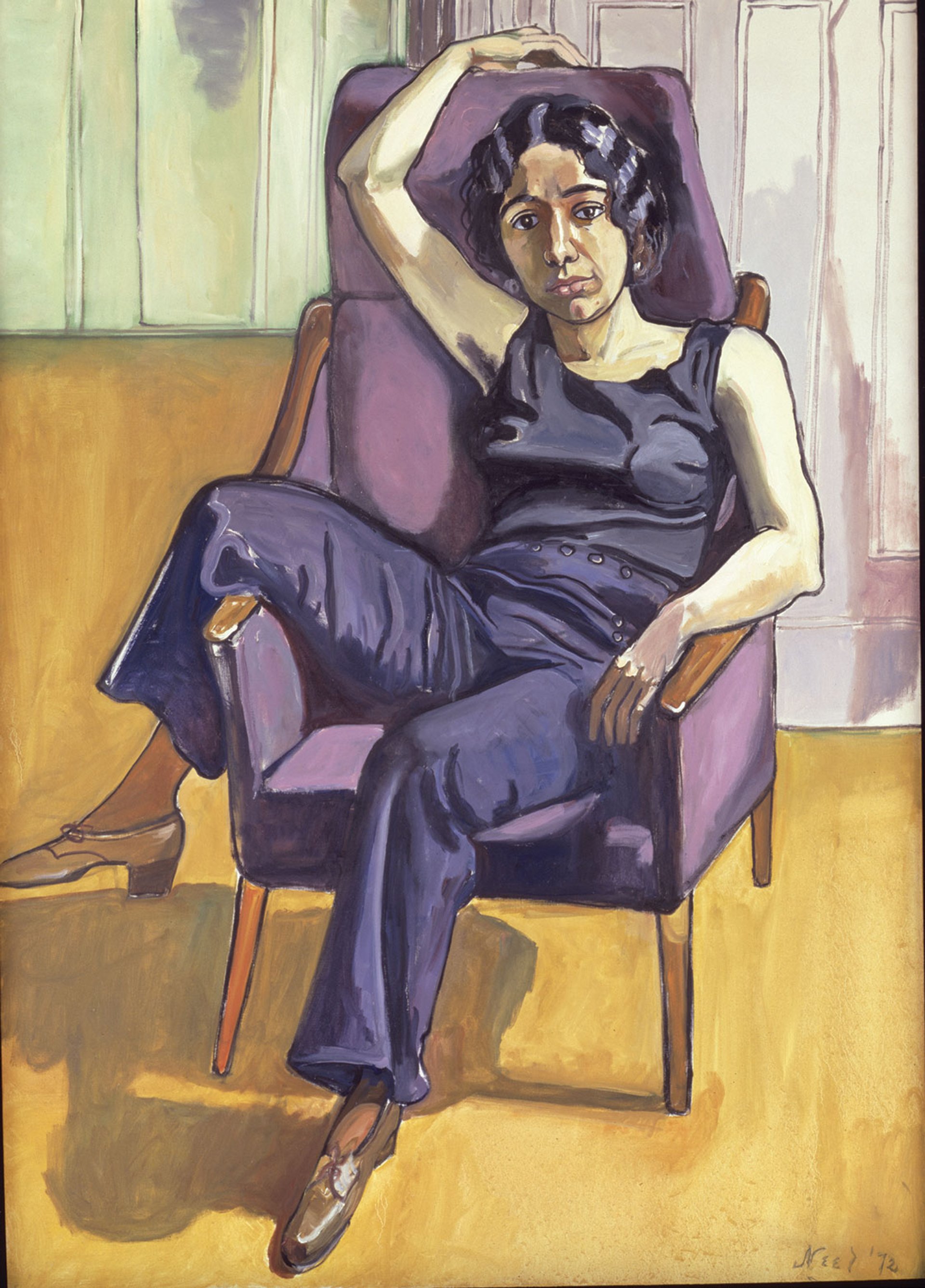

The subject of Alice Neel’s painting Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis) (1972)—a founder of the New York Feminist Art Institute—presides over a worn purple chair like a self-possessed sovereign of bohemia. Peslikis’s right leg hangs over the armrest while her curling right arm shows off an unshaven armpit. Those brownish-black eyes confront us with a glare that is vulnerable yet not uninviting, as though she is too afraid to ask: “who the hell are you?” To her left, affixed on a blue wall under the vaulting industrial pipes of the Centre Pompidou is the double portrait Wellesley Girls (Kiki Djos ‘68 and Nancy Selvage ’67) (1967). In their preppy skirts and tights, painted under a harsh fluorescent light on a weekend trip to the city, they display the essence of middle-class naivety while social revolution rages outside.

Neel’s Marxist Girl (1972), a portrait of the feminist Irene Peslikis. © The Estate of Alice Neel; courtesy of David Zwirner and Victoria Miro

Among others, they rub shoulders with Life magazine editor David Bourdon (purring like “the cat that’s got the cream”, according to Neel) and Gregory Battcock, the legendary secret-keeper of Manhattan’s queer gossip (whose stern expression resembles, oddly, “an Asturian miner”). The exhibition features 70 such works of Neel’s friends, her sons, their ex-girlfriends, loners, drop-outs, draftees, revolutionaries, expectant mothers, poets, museum curators, and strangers off the street. It is a veritable who’s who of the human carnival. It is a whole life in art.

Born on 28 January 1900, “four weeks younger than the century”, as she liked to say, Neel is perhaps the most astute and penetrating people-watcher of that tumultuous century of American history. She was painting right up until the moment of a particularly spectral photograph taken by Robert Mapplethorpe in 1984—included in the show—that depicts the artist just a week or so before her death.

Another work on display, by Jenny Holzer, is a wonderful fragment of biography: in 1955, when federal agents came to interrogate her over her Communist Party membership, Neel unsuccessfully tried to get them to sit for a painting.

To write that Neel is having a moment reads like an understatement. People Come First, the largest Neel retrospective yet staged in New York, monopolised the Tisch Galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art last summer. The New York Times said that she was “equal if not superior to artists like Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon” (a grand claim), “and destined for icon status on the order of Vincent van Gogh and David Hockney” (even grander). People Come First then travelled to the Guggenheim Bilbao and the De Young Museum in San Francisco. Rave reviews followed wherever it went. This Parisian show will travel to London’s Barbican Art Gallery in February next year, in a slightly altered form and retitled Hot Off the Griddle. The phrase comes from Neel’s freewheeling manifesto of style: “One of the reasons I painted was to catch life as it goes by, right hot off the griddle.” That is exactly how these paintings feel.

Figurehead of figuration

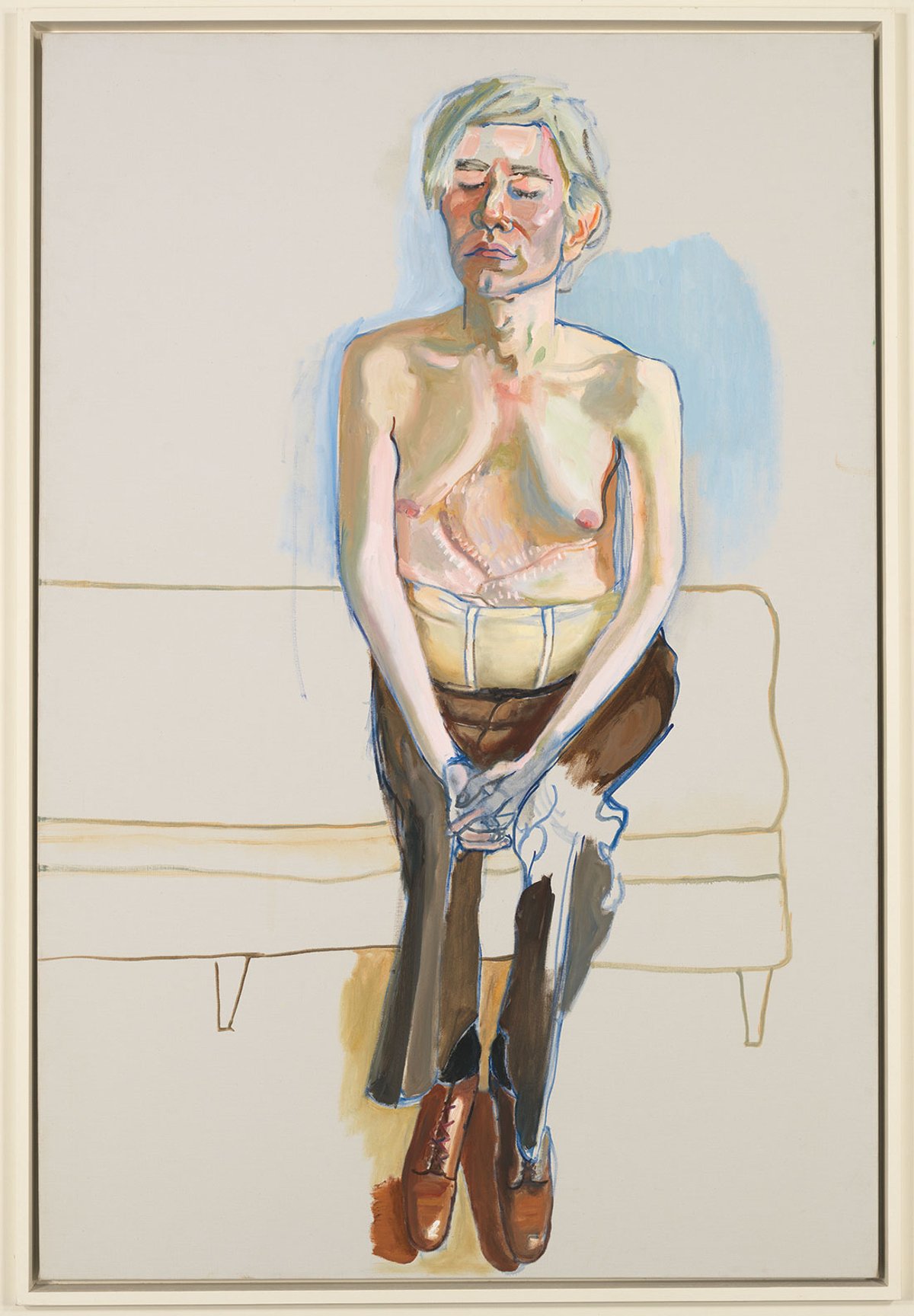

Neel’s paintings are even more extraordinary given their strident commitment to figuration, all the while New Yorkers could not make up their mind over whether the future of Modern art belonged to gestural abstraction, Pop, Minimalism, the downtown happening or anything else. While they argued, Neel was there to paint them all. A tender portrait of a skinny Andy Warhol in 1970, two years after he was shot by Valerie Solanas, has his mangled and saggy chest barely held together by stitches. His eyes are closed in contemplation like a martyred saint. Andy Warhol is one of several portraits that look unfinished, and utterly perfect for being so.

Another example of this mode, Black Draftee (James Hunter) (1965), depicts a young man who has just been drafted after Lyndon B. Johnson drastically increased ground forces in Vietnam. The distracted and forlorn expression on his face, and the hand that holds it up from plunging completely, is rendered in radiant colour; his body remains in outline. When Hunter did not come back to her studio for a second sitting, Neel declared the work complete: a testament to the possibilities of youth, of what was started with attention and purpose but could not be finished. It is dedicated to an entire generation who never returned from the Vietnam War.

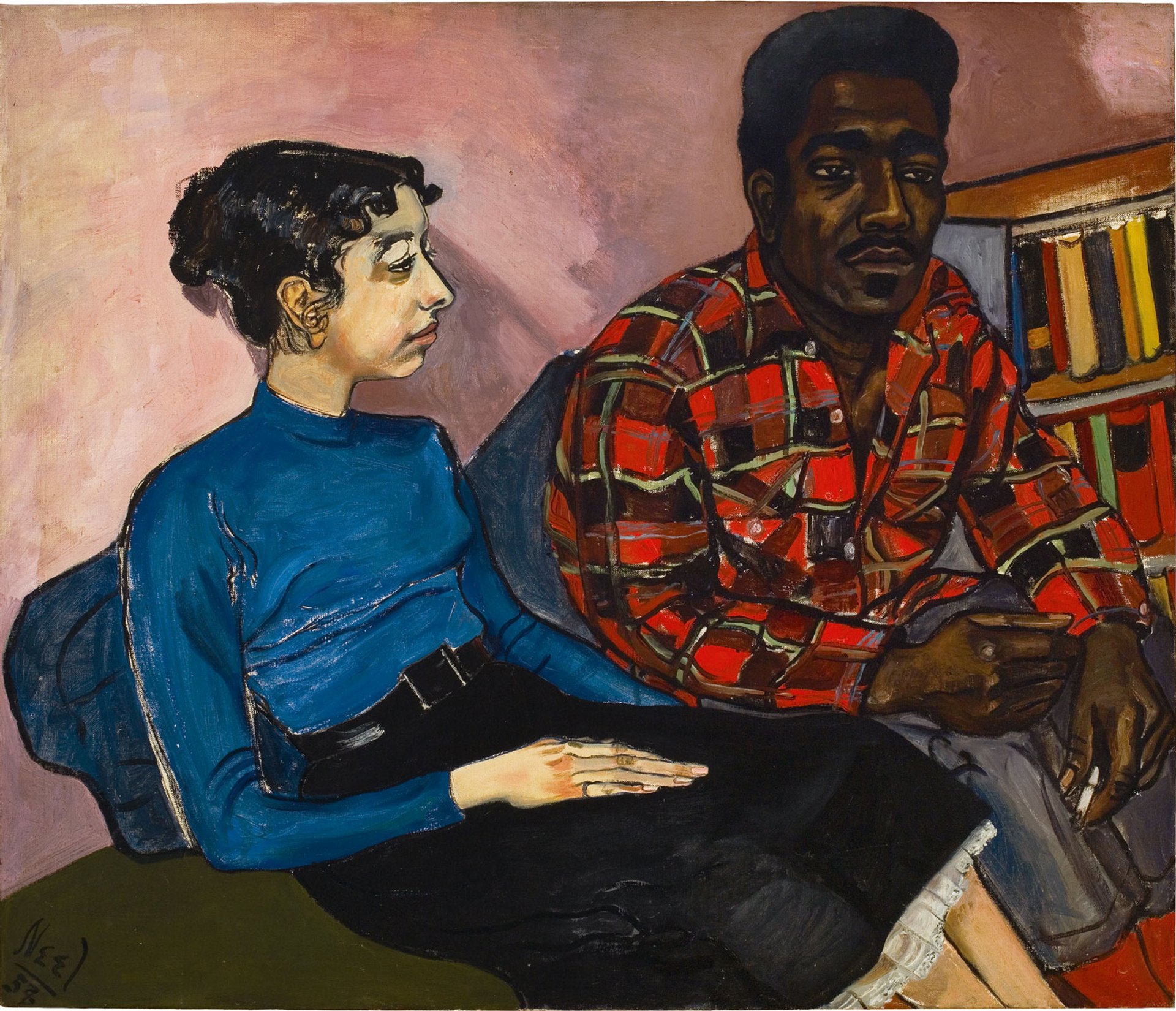

Neel’s Rita and Hubert (1954). Photo: Malcolm Varon; © The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner

Elsewhere, the Fluxus artist Geoffrey Hendricks and his open-shirted lover Brian Buczak are pictured like tired-eyed hipsters wearing their clothes from the night before. It looks every inch like it was painted today, not nearly half a century ago, such is the extraordinary influence that Neel exerts on contemporary figuration right now, especially in New York.

The artist’s second portrait of Frank O’Hara, the poet laureate of Abstract Expressionism and the movement’s most unflinching supporter at the Museum of Modern Art, is depicted here warts—or rather pallid freckles—and all. Neel reflected how her first portrait, which was made over five lengthy sittings (and is not on show in Paris), saw O’Hara resemble “a romantic falconlike profile with a bunch of lilacs”. No. 2 (1960), on the other hand, was made in half a day: O’Hara looks crippled by the anxiety of a hangover and the lilacs have withered. Neel wanted to capture how “beat” he looked when he walked through the door: “I feel that it expressed his troubled life more than the first.”

The O’Hara pairing feels like a wasted opportunity to tell a narrative, and if this exhibition misses at all, it is because not more is made of coupling portraits of the same sitter at different moments of their lives—and across Neel’s decades-long aesthetic experiments. This curatorial approach was taken up in There’s Still Another I See, which opened at Victoria Miro gallery in London last month (until 12 November). It is a wonderful display that demonstrates Neel’s remarkable ability to paint the same sitter in radically different styles, and yet be so palpably recognisable as both themselves and as a Neel portrait.

The engaged eye of Neel’s Parisian outing is certainly her own, but it is also a quality of all her subjects who animate a fascinating carousel of honest pictures, touchingly present in their puffed-up eyes and heads, which are invariably about a tenth bigger than they should be. They resemble feral children in an adult’s world; they are inquisitive and alive. “In politics and in life, I always liked the losers, the underdog,” Neel wrote. If Neel loved her sitters briefly or for a lifetime, and loved them for their insecurities, imperfections, beauty, and the sheer torment of what it feels like to be adrift in the modern world, then we leave loving them a little too.

What the other critics said about the exhibition

Much of the French critical reception focuses on the political nature of the exhibition, especially the works’ engagement with American class politics and Neel’s brave depiction of race. Philippe Dagen, writing in Le Monde, describes Neel as a “ghost” or “spirit” (perhaps a reference to Robert Mapplethorpe’s 1984 photograph), who was long overdue proper recognition in France: “Neel does not seek to seduce, but to warn about the reality of the time.”

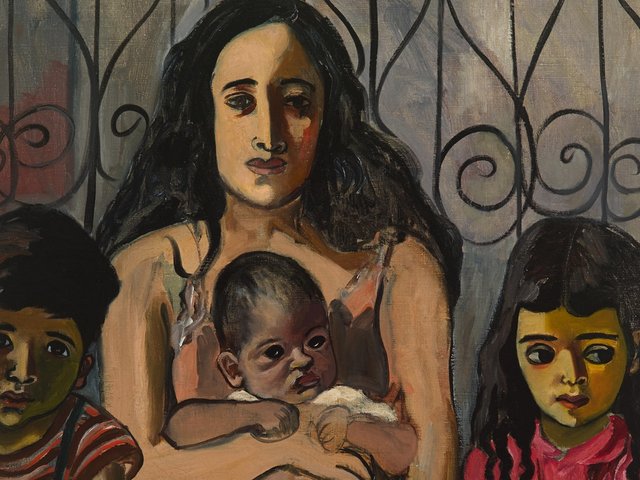

In the French financial newspaper Les Echos, Judith Benhamou also focuses on the political nature of portrait painting in the 20th century. “Having one’s own portrait made has long been a way of attaining immortality,” she writes, before explaining how Neel married an expressionist style with caricature to “express the psychology of her characters” who were “never royalty or the ‘rich bourgeois’”.

• Alice Neel: an Engaged Eye, Centre Pompidou, Paris, until 16 January 2023