The Brazilian artist Maxwell Alexandre, whose exhibition Pardo é Papel: The Glorious Victory and New Power opens at The Shed in New York this week, has enjoyed a galvanic rise in his country’s contemporary art scene and internationally. Alexandre combines fierce entrepreneurship–gained in his earlier life as a skateboarder promoting his own career and in design school—and the boldness of a cultural and social outsider.

He first made his mark by answering an open call by Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel gallery in his native city of Rio de Janeiro. Though the rules of the call stipulated that the work had to be on a smaller scale (it had to fit in the door), Alexandre chose his largest work, executed on what is by now his most recognisable material, brown craft paper, and rolled it up to pass through the entrance. Once reminded of the rules, he insisted that he had met them—he was already inside.

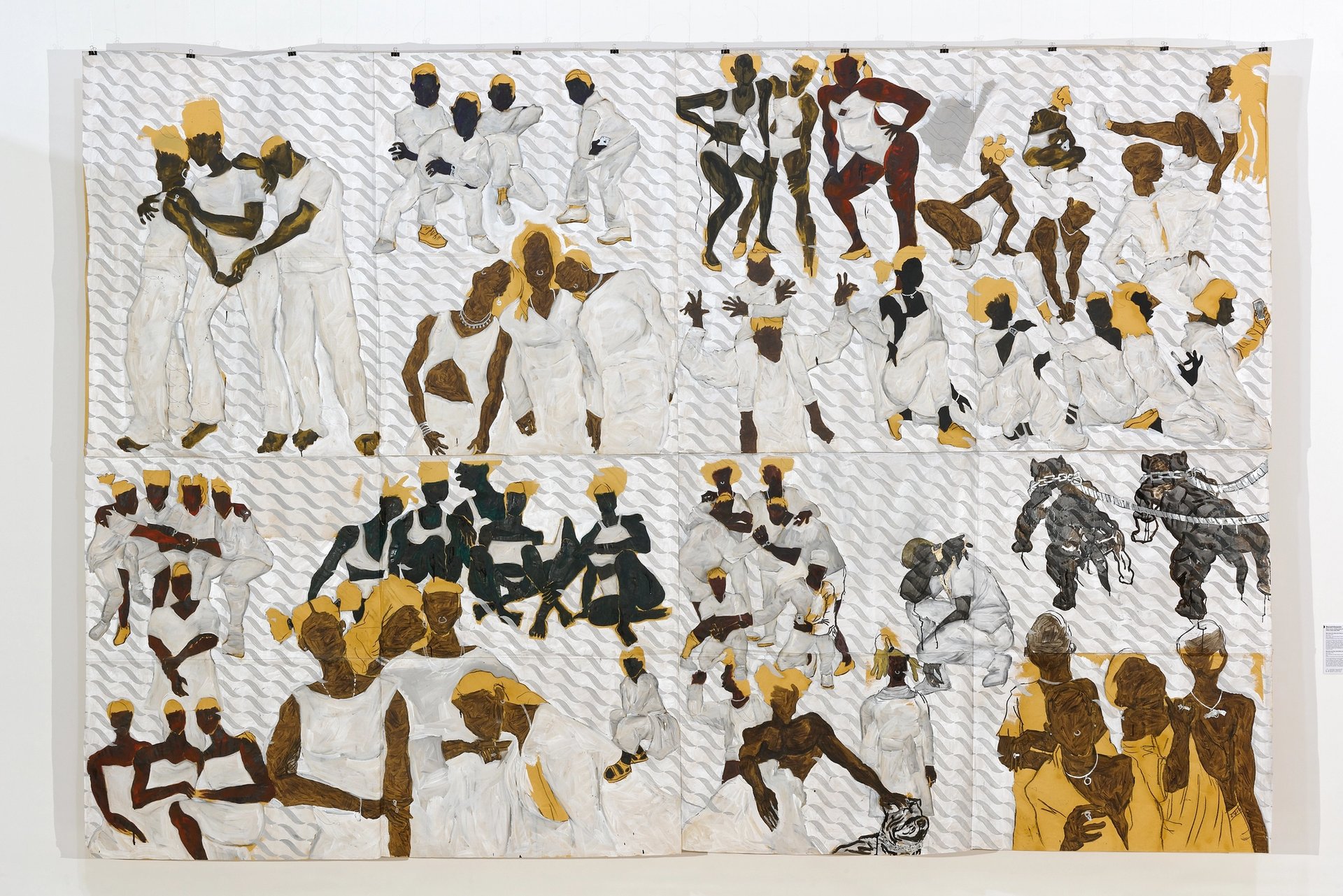

Alexandre’s works, which move fluidly between shorthand silhouette figuration, rich patterning and sparse abstract detail, often unfold narratives of Black Brazilian communities. Populated with local scenes of Alexandre’s neighbourhood of Rocinha, they exult in religiosity, popular culture, markers of social mobility and leisure activities. But as his latest works also show, he is deeply interested in how the bodies of Black spectators interact with cultural scenes and institutions.

Maxwell Alexandre, Meus manos, minhas minas, meus irmãos, minhas irmãs e meus cães (My homies, my homegirls, my brothers, my sisters and my dogs) (2017–18) from the series Pardo é Papel: The Glorious Victory (2017–ongoing). Courtesy Fortes D'Aloia & Gabriel. © Maxwell Alexandre. Photo: Gabi Carrera. Courtesy Instituto Inclusartiz and Museu de Arte do Rio – MAR.

The Art Newspaper: The current presentation at The Shed is the sixth iteration of the show, which was on view in places such as Lyon, Paris and Berlin. Can you talk about the interrelation between the works from the Pardo é Papel series (2017-ongoing) featured in it and the newer works that are also on view?

Maxwell Alexandre: Pardo depicts some of the traditional professions that help Black people climb socially in Brazil—soccer, music, etc. Art isn’t one of them, but it’s present through my work, as an invitation to “vadiar,” to embrace leisure, a sense of doing nothing, of revelry. The first step of the ascendancy I depict are material goods—bags, clothes, etc—linked to ostentation, which white people view with contempt. But culturally, ostentation shows that we’ve achieved something, which is what Pardo é Papel is about. In New Power (2019-ongoing) I go beyond this. My invitation is to see that our life is connected to our subjectivity. Contemporary art is one of the places where we have the space to dream in a more defined form. For what’s more superfluous than art? That’s the “new power” for my community.

You transitioned to figurative painting early in your career. What informed this transition?

I come from a design background. At the design school, I was doing skating, which is not just a sport but a culture. Then, by the time I studied at PUC-Rio in Rio de Janeiro with the Brazilian painter Eduardo Berliner, I already understood that I was an artist. But I come from a Christian family in the favela Rocinha with no reference of what it means to have a higher education. I felt a lot of pressure, struggling with the notion that education ought to bring me the stability I lacked. Working with abstract art was at first a way of mediating this pressure.

Did you make a conscious choice to be a painter?

I was actually doing photography and video before the university and making skating products. The actual sense that I was painting came to me only in 2017. I was experimenting with different materials. For example, wall paint, which is more matte and porous, or shoeshine, with which I paint Black skin. I used materials linked to my daily life that I had an affinity with because of their scent. When I paint with hair relaxer, for instance, there’s a poetic and political charge to the work, because it’s part of the history of Black women’s lives in the favelas. It’s the scent of my mother and sister. But when I first used it I wasn’t yet thinking of its political dimension. It was more of a pictorial and economic decision.

Some of my friends approach painting with an almost religious reverence. But because of my background I didn’t have this baggage; I didn’t ask for a permission to paint. Once I emerged, people began telling me to work on a smaller scale, not to use brown craft paper that doesn’t last, and offering me sophisticated paints. I resisted. My last presentation at ArtRio included some works in oil, but I didn’t make them available, not to feed the fetish of oil painting.

I produce a lot and fast. In a way, I’m not a painter. My education is in visual communication, in design and anthropology. My curiosity is anthropological. Today, with a bigger studio and team, I feel more like a director. The idea is to get more distant from painting, to be more conceptual.

Maxwell Alexandre, sem titulo (Untitled) (2022) from the series Pardo é Papel: New Power (2019–ongoing). Artwork courtesy the artist and A Gentil Carioca. © Maxwell Alexandre. Photo: Thiago Barros.

In this sense, Warhol seems like an important reference.

For sure. Perhaps the greatest one, though his work seems more collaborative. I think of the Factory as a place where people participated in productions. My work is more centralised—personal. But I’m certainly referencing Warhol; even the name, Factory, is important to me.

How does your interest in anthropology connect to your choice of figurative art?

Figurative art allowed me a place of exclusivity. Today there’s a paradigm: it’s expected that a Black artist do Black figuration—it’s become our prison. But Black Figuration was lacking in the history of art—who are the Black masters?—and my place has to do with my being favelado, not just Black but also working with the symbols of the favela. It’s a fetish, something that others want to consume, but that didn’t exist, except as a souvenir, or in naïve art.

I wanted to do self-portraits and to paint a Black person with blond hair. In the favelas, a Black man with blond hair, like mine at the time, was marginalised, because this aesthetic is embraced by criminal factions. The response to it was very violent: if the police saw you in the street they stopped you as a drug trafficker. The violence of racism sequestered our dignity. The other day, I met Black children at a local school who asked me for a paint in the color of skin. When I offered them Black paint, they bolted. They paint skin color as pink. That’s so violent.

Maxwell Alexandre, Se eu fosse vocês olhava pra mim de novo (If I were you I'd look at me again) (2018) from the series Pardo é Papel: The Glorious Victory (2017–ongoing). Courtesy Fortes D'Aloia & Gabriel and A Gentil Carioca. © Maxwell Alexandre. Photo: Gabi Carrera. Courtesy Instituto Inclusartiz and Museu de Arte do Rio – MAR.

Let’s talk about the word “pardo” which features in the show’s original Portuguese title.

Pardo is used to identify Black people with light skin. My ID identifies me as pardo. This denomination has been part of the racist history of whitening in Brazil—of hiding negritude. Pardo paper is also brown craft paper, which I used working with fashion at the university. I’d pick up pieces that were being used for drafting clothes. I chose this paper for my self-portrait, because its yellow color is very seductive. It’s not desaturated; it has a certain sophistication.

I call my process “shorthand painting”: brown paper helps me resolve aesthetic questions quickly; brushworks of yellow, white, or blue paint work well on it. Later I understood that to paint Black people on brown paper was to create a counter-narrative to the denial of Blackness.

- Maxwell Alexandre: Pardo é Papel: The Glorious Victory and New Power, 26 October 2022-8 January 2023 at The Shed, New York.