“Prolixity is not alien to us in India,” wrote the economist and philosopher Amartya Sen in his acclaimed book The Argumentative Indian (2005). “We do like to speak,” he added. Moving Focus, India: New Perspectives on Modern and Contemporary Art, edited by the gallerist and SOAS postgraduate Mortimer Chatterjee, founder of Chatterjee & Lal (Mumbai), is testimony to these assertions.

Born of late-night conversations among friends arguing about the works that mattered most, this two-volume publication brings together a selection of art hits compiled by 54 contributors: a range of artists, curators, writers and historians from the international Indian art world. Akin to a Desert Island Discs model, each nominator chose five works, each work then qualified by a short text and the whole collection contextualised by eight essays and a transcribed roundtable discussion.

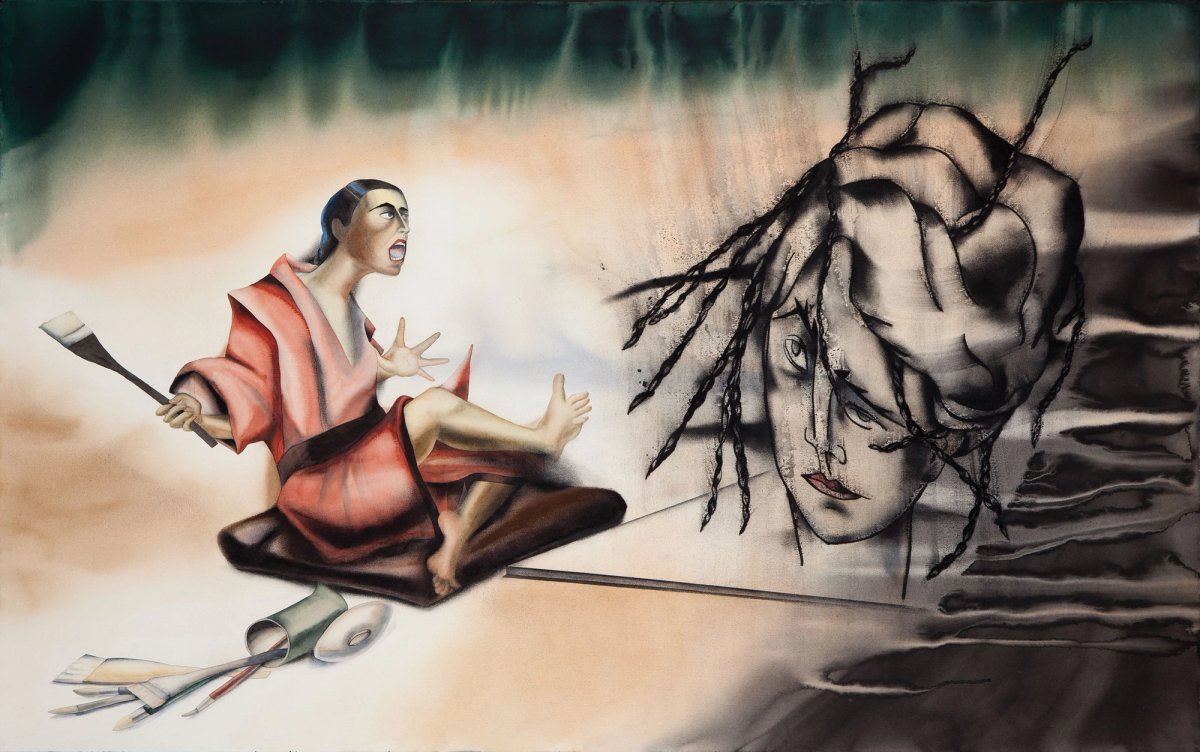

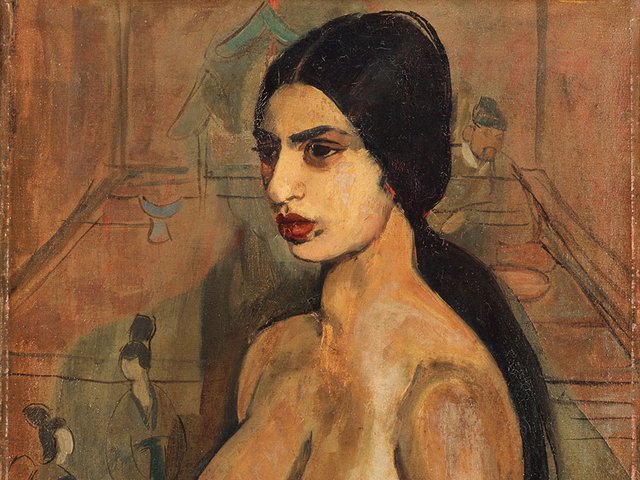

Both loquacious and visually abundant, Moving Focus, India is a sprint through many opinions, and replete with the inevitable contradictions and crossovers that any collective endeavour entails. It is both a revealing and unenviable task to whittle down Modern and contemporary art-making and then select your cream of the crop. The aggregation of tastes throws up some expected selections skewed to more established artists: the gloriously intensive studies of daily life by India’s “first Pop artist”, Bhupen Khakhar, a key national and international figure in 20th-century painting, appear five times; contemporary painter Anju Dodiya’s figurative watercolours (often with charcoal), evoking intense autobiographical and psychological dramas, are nominated four times.

But the idiosyncratic selection process ensures that there are many intriguing and refreshing choices. Diva Gujral, an associate lecturer at University College London, selects the performance artist Amitesh Grover’s poetic text projections, No.90 (2020, from Velocity Pieces), that shone from display boards at New Delhi’s Goethe-Institut.

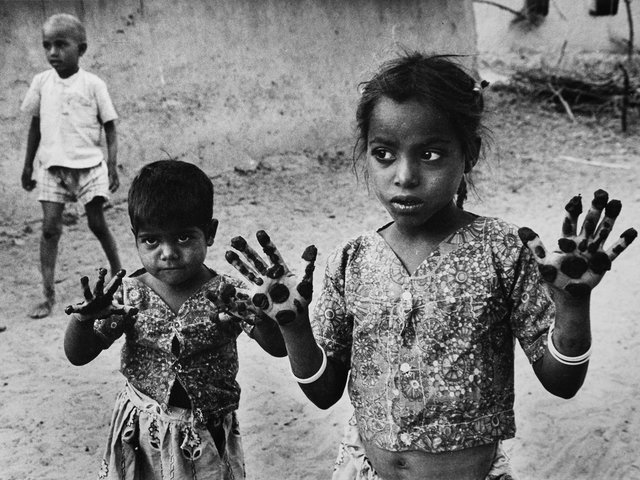

Untitled (1980), a multidimensional tapestry created by weaver, textile designer and craft activist Nelly Sethna, is one of the selections by the artist and curator Ushmita Sahu, while the Kolkata-based former sports journalist Kushal Ray’s photobook, Intimacies (2012), charting an adoptee’s experience of life with a new family, was chosen by the photographer Sohrab Hura (a member of the international co-operative, Magnum Photos).

Weaver, textile designer and craft activist Nelly Sethna’s multidimensional tapestry Untitled (1980)

Courtesy of Chatterjee & Lal

In tandem with Thames & Hudson’s recent publication, 20th Century Indian Art: Modern, Post-Independence, Contemporary (see review in The Art Newspaper, June 2022, p68), the ambition to avoid any reductive canonising tendencies drives all aspects of the current study: from the generous remit for selection—a creation date from 1900 onwards, incorporating design as well as fine art objects, and by artists based in India or identifying as part of its diaspora—to the organisation of chosen works by visual affinities and the lively essays that lambaste the ‘canon’.

While less scholarly than the Thames & Hudson volume and by no means proposing a full-loaded guide to Indian art of the period, Chatterjee’s publication does propose a different way of comprehending Modern and contemporary art through key “memory sites”, a term conceptualised by the French historian Pierre Nora: certain events, objects, people and languages that are held in collective memory and form the basis of a shared identity for those in the Indian art community. As Nora asserted, these sites are never static but are the basis upon which ideas from the past are retrieved and continue to be reassessed.

For Chatterjee, six sites give shape and provide footholds of meaning for the Indian art world: Ramkinkar Baij’s Santhal Family (1938), considered the first public Modernist sculpture in India, representing villagers of the West Bengal tribe; the Progressive Artists’ Group of Bombay (1947-1954), among them F.N. Souza and V.S. Gaitonde, who challenged the conservative art establishment; the Artists of the Third Epoch (1950s-1970s), including K.S. Kulkarni and Satish Gujral; the artists, school and movement around the Gujarat city of Baroda between the 1960s and 1990s; the book Thought-Forms: A Record of Clairvoyant Investigation (published 1901), conceived by the British theosophists Annie Besant (supporter of Indian self-rule) and C.W. Leadbeater; and the 1992 demolition of the Ayodhya mosque, Babri Masjid, and the associated Bombay riots of 1993. Chatterjee provides a quick whip around these tangible and intangible moments, ultimately imparting their continued relevance.

There is remarkable joy in poring over this extensive compilation. For the insatiably curious, the individual rationales for selection are illuminating and often candid, while the stock of writing tackles some of the thornier debates that haunt the field.

Curatorial responsibility is addressed by Shanay Jhaveri and Madhuvanti Ghose, curators at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and Art Institute of Chicago respectively. Their essays expand on the practicalities of spearheading acquisitions from the region and its diaspora with strategies that allay the late start of these institutions’ interest. Geeta Kapur, the New Delhi-based art critic, art historian and curator, addresses how hegemonic modernism sees power in this hitherto tangential position, regarding art operating “outside the West but inside the international” with the privilege of negotiating between the two.

With contributions that consider the foremost public and private collections of Indian art and the museum history of the British-initiated Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum in Mumbai (founded in 1855), Chatterjee strikes a welcome balance of content, tempering dense theoretical discussions with the whimsy of personal judgment. Given the many questions that emerge as a result, coupled with Chatterjee’s evident penchant for conversation and debate, there is every hope that a follow-up book is on its way.

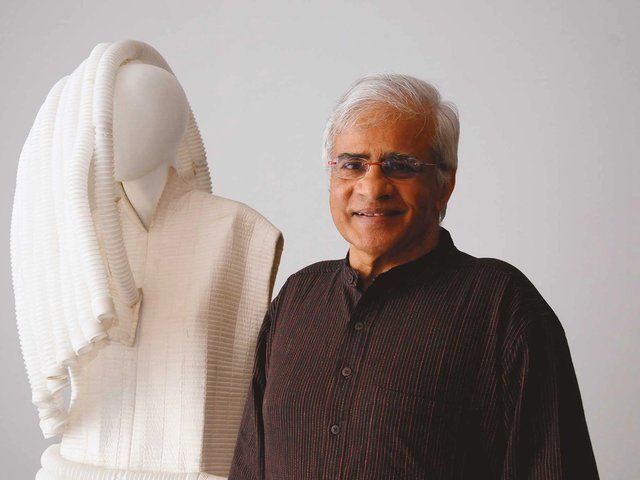

Mortimer Chatterjee (ed), Moving Focus, India: New Perspectives on Modern and Contemporary Art, ACC Art Books, 2 vols, 616pp, 1,000 colour illustrations, £75/$95 (pb), published 1 June

• Cleo Roberts-Komireddi is a speaker and writer on contemporary South and Southeast Asian art. She has written for The Financial Times, The Guardian and Frieze. She is the director, artists and research, at Edel Assanti Gallery, London