Spare a thought for our friends at Arts Council England (ACE). This summer they have been reviewing a record 1,730 applications to ACE’s National Portfolio of regularly funded organisations. Those chosen—to be announced in October—will receive regular public funding (government and Lottery) from ACE. It’s the mechanism that supports many of England’s key visual arts organisations, such as Kettle’s Yard, Artangel and Turner Contemporary, as well as museums up and down the country. While you were lazing on the beach this summer, ACE officials were making some of the hardest decisions of their lives, with agonising trade-offs and painful contortions required to satisfy two opposing goals—of its own.

On the one hand, there are the stated aims of ACE’s new strategy, ‘Let’s Create’, designed “to recognise and champion the creative activities and cultural experiences of every person in every town, village and city in this country”, which generate all manner of economic, health and social benefits. On the other, there is the expectation from an entire sector that has evolved to match an older ACE mission to support the “knowledge, understanding and practice of the arts”, for its own sake, by as many people as possible.

Luckily for ACE, there is now a large body of social science to inform its deliberations. A decade of research has uncovered certain fundamental principles, which, if taken into account, ensure that ACE stands a good chance of investing in a way that achieves its latest stated aims.

‘Let’s Create’ aligns with current thinking that sees cultural participation as a means to accumulate and spend a form of capital. It is increasingly unfashionable to say that culture is supplied to people or done to them. This capital doesn’t simply appear by magic when someone interacts with an ACE-funded organisation. And it can often result from conditions that are outside the control of any one arts organisation. A complex set of forces determine whether people are likely to engage in the first place, and what that engagement might achieve. The forces in question are familiar: someone’s knowledge, attitude and demographic characteristics. This is irrespective of whether the art is any good or not.

Culture is increasingly understood in terms of an ecosystem, with complex feedback loops between funding, programming, infrastructure, governance, policy, education, media, technology, fashions and lifestyles. No serious policymaker thinks in terms of isolated ‘interventions’: a project here, a building there, a festival somewhere else. ACE is one of those rare entities with the ability to think on a grand scale and act in ways that affect the health of the entire cultural ecosystem. It can make the weather and will want to use the aggregate of all individual decisions this summer to ensure the conditions are right for the kinds of outcomes articulated in ‘Let’s Create’.

Participatory, not passive

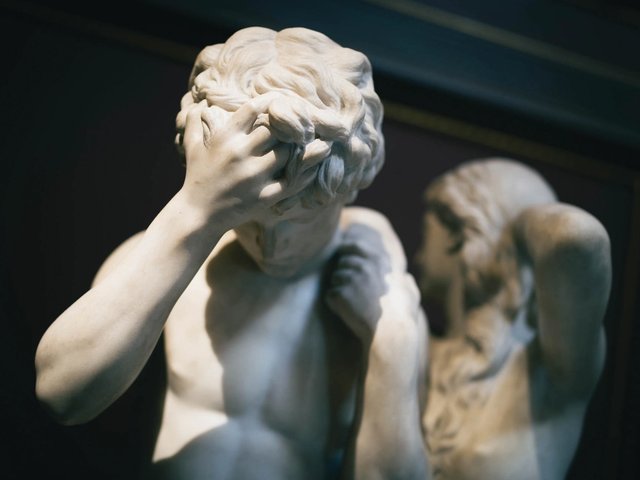

Those social outcomes—such as improved health and wellbeing, vibrant local economies, fulfilled creative lives—derive from activities that are participatory rather than passive, that foster group interaction rather than solo contemplation, that are structured and sustained rather than casual and infrequent, and are built from the bottom-up rather than imposed in a top-down fashion. You don’t tend to get these social benefits of culture by walking into a grand building, handing over £20 and spending 90 minutes shuffling past a series of paintings.

The irony for ACE is that many artists and organisations have always been doing what ‘Let’s Create’ asks of its applicants. Yet the most impactful DIY cultural interventions have tended to attract the least funding and support from policymakers. Maybe this is what has made them so effective?

Those unloved parts of the sector have focused on creating a quality experience for ordinary people in non-traditional settings, but because that hasn’t conformed to elite aesthetic norms it has been overlooked. They have been enterprising and entrepreneurial. They have been serving diverse local communities because they are born of those communities—not parachuted in from some well-meaning but misguided philanthropists. They are part of a counterculture that pushes against a political and cultural establishment that prizes glitz and glamour.

This is historically the stuff of community arts, not the elite institutions that have done so well from decades of ACE subsidy. Those impactful leaders aren’t the sort of people who fill out forms in technical language and supply bureaucratic documentation because they have been busy making things happen in the real world, not the Arts Council world.

If the new settlement is as radical as ‘Let’s Create’ gives us to understand, then it will delight the advocates for change and upset the establishment. So, make a note in your diaries: we may be due an October Revolution—if ACE dares to keep its promises.

• James Doeser is an arts consultant and researcher