An eminent art historian provided more than a dozen letters of authenticity to James Stunt, the controversial socialite and businessman, for paintings that were not considered genuine or by the hands of the artists, including the major Old Master portraitist Anthony Van Dyck.

Malcolm Rogers, an expert in British 17th- and 18th-century portraiture and a former director of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, attributed to Van Dyck works that were previously bought by Stunt, having sold cheaply at auction or via private sale as outright copies or as studio productions. Some of these newly discovered works were then sent by Stunt to be exhibited in Dumfries House, the Palladian estate in Scotland now owned by King Charles’s charitable foundation.

Rogers apparently had a close relationship with Stunt, a bankrupt businessman who has been on trial for money laundering in the UK—a charge he denies. In 2019 the Mail on Sunday revealed how Stunt lent several paintings to Dumfries House, some of which turned out to be fakes, including a Monet and a Picasso.

An investigation by The Art Newspaper now reveals that seven of the Rogers-attributed paintings were among those sent by Stunt to Dumfries House: five “Van Dycks”, one “Goya” and one “Velázquez” (the latter two outside Rogers’s traditional area of expertise). Three of the “Van Dycks” were, however, described as “absolute copies”, by the scholar Susan Barnes. In a 2020 email seen by The Art Newspaper she wrote: “When and why they were made, I can’t imagine.” Barnes is a co-author of the authoritative Van Dyck catalogue raisonné, along with Nora De Poorter, Oliver Millar and Horst Vey.

Reattributions of seemingly insignificant works to important artists are rare, and it is extremely unusual for a single expert to provide 12 letters to a single collector about a single artist (Van Dyck). They are known as “sleepers” in the trade, but for the same person to discover and reattribute 14 paintings is even more extraordinary and surprising.

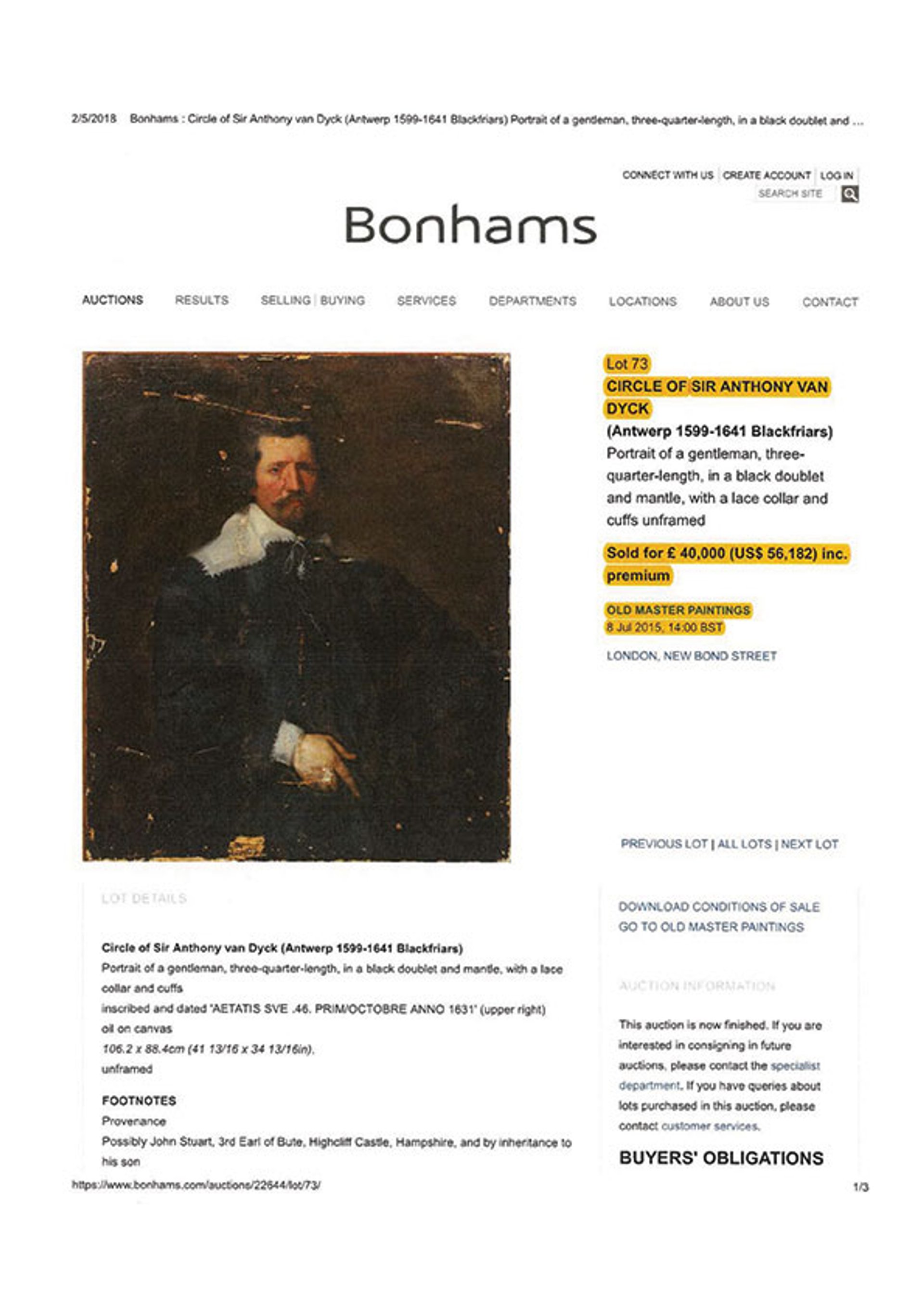

Among the works that Rogers reattributed to Van Dyck was Portrait of a Gentleman in Black, bought at Bonhams in 2015 for £40,000 as “circle of” and not in the artist’s catalogue raisonné, which Rogers wrote in a 2016 letter to Stunt was “autograph throughout” and which Stunt then valued at £10m when it was shown at Dumfries House.

Another example was the Portrait of the Earl of Kinnoull bought as “circle of” at Cambi Casa d’Aste in Genoa in 2016 for £25,000 and subsequently valued at £8m. Rogers wrote that it was “clearly an autograph work” in a letter to Stunt in 2017, although it was described by Susan Barnes as an “absolute copy”.

Bonham’s online record of a portrait it described as “circle of” van Dyck, which Rogers attributed to the Dutch master

The value of the Dumfries House upgrades was about £70m (the difference between the purchase price and the insurance value on the contracts). In total, our records show, Stunt paid just £357,450 for the seven works.

Rogers also told a close aide of Stunt, “We can do more” in a 2018 email discussing values and letters of attribution.

When asked about these findings by email in August this year, Rogers responded: “In common with the practice of most scholars of my generation, I do not ‘authenticate’ works of art, but I am often asked to give opinions on works that fall within my area of scholarship. As opinions they are naturally open to challenge by other scholars. I stand by the opinions that I have given, but would emphasise that they can in no way be considered ‘authentication’… nevertheless, my letters—as you will know if you have read them—are closely argued and evidence-based.”

While it is not an unusual practice for specialists to be paid for giving their opinions on works of art, Rogers told The Art Newspaper that he did not receive payment for the extensive work that he did for Stunt—“At no time have I done so in the case of Mr Stunt”—although he said that “[Stunt] did on occasion pay for travel expenses incurred in my research and funded the purchase of some reference books. He also, from time to time, made gifts to me as tokens of appreciation.” Rogers declined to communicate a value for these.

Rogers also said: “We [he and Stunt] met, but not on a regular basis.” However, according to Stunt’s former head of security, Vilius Gabsys, Rogers was a “frequent visitor” to Stunt.

Ali Dizaei, a former commander of the Metropolitan Police, was in charge of Stunt’s legal, financial and security teams. His team researched and catalogued all of Stunt’s assets.

“When my company was working for Stunt we were not getting paid and so we decided to investigate Stunt’s assets because I was worried that my employees and colleagues would not get paid,” Dizaei said. “I needed to protect our exposure. We did our research and noticed that James Stunt appeared to have an ability for discovering paintings which were not well-known.

“We then found out that these paintings were passed by a man called Malcolm Rogers and we noticed a large number of paintings. During our investigation it seemed to us that they were bought for a relatively low amount and then Mr Rogers would write a letter that said the art was authentic. And then, as a result, those same paintings would be valued for millions of pounds and appear on the register as very valuable.”

Rogers denies this, saying: “Stunt made the majority of his purchases on the open market from established, mainly London, art dealers, and paid retail prices. A few items were purchased at public auction. These works were catalogued as [being] by Van Dyck or from his studio, some of the former supported by opinions from Susan Barnes. I do not recall any catalogued as copies. In any case, it is naïve to think that my opinion had the effect of ‘greatly increasing their value’.”

Stunt’s ‘payments’ to Rogers

According to Dizaei, “We were in a situation when my company needed to take a Restraining Order out against Stunt so that we would get paid. And we needed to find out about his expenditure as well as his income. It was then that I remember noticing documents which showed payments from Stunt to Rogers.”

Vilius Gabsys said: “I worked for James Stunt for six years and was based in his house in Belgravia and so knew what was going on. I would see lots of people coming and going and one of his most regular visitors was Malcolm Rogers, the art historian. He would come by once a week, sometimes more. I would definitely see him a few times per month. I remember that James always expected Rogers to send him a positive email, not a negative one. James was happy when he received these emails, which always said the paintings were for real.

“And so James would sit around talking with Malcolm Rogers about the paintings. I would then drive him to the station or drive him all the way home, which took about three hours, and I would often give him an envelope from Stunt.” It is not known what was in the envelopes.

In a separate arrangement, Rogers owned a copy of Van Dyck’s Cardinal Infante and records show he paid £10,000 for it at auction. A few years later, Stunt ended up owning this painting and it bears Rogers’s letter of attribution, and so would now be worth many times this sum. He told a source that he “swapped” the Cardinal Infante with Stunt for another painting but declined to say which painting this was, or its value.

However, and bearing out his position, Rogers told The Art Newspaper that this work was considered authentic by Susan Barnes and she confirmed to us that “his version closely follows the preliminary drawing in the British Museum and it represents a first draft of the composition”. Barnes was not prepared, however, to offer further clarification, nor respond to our questions on the other reattributions.