Since 1952, a 20-foot painting of Robert E. Lee in his Confederate uniform has hung in the library of the US Military Academy (USMA) at West Point, New York. That portrait, as well as several other pro-Confederacy markers and displays on the Hudson River Valeley campus, may soon be removed, as recommended by a Congressional commission tasked with assessing the display of Confederate-related names at US military bases.

The Naming Commission was established last year to issue recommendations for items across the Department of Defence (DoD) that “commemorate the Confederate States of America or any person who served voluntarily with the Confederate States of America”. In May, its eight-member panel suggested new names for nine Army bases that honoured Confederate officers. Their latest report, released 29 August, addresses DoD assets ranging from plaques to reliefs at USMA and the United States Naval Academy (USNA) in Annapolis, Maryland. The committee is recommending that many of these be renamed, while others be modified or removed. Only roll calls of graduates have been advised to be left unchanged.

“The Commissioners do not make these recommendations with any intention of ‘erasing history’,” the report states. “The facts of the past remain and the Commissioners are confident the history of the Civil War will continue to be taught at all Service academies with all the quality and complex detail our national past deserves. Rather, they make these recommendations to affirm West Point’s long tradition of educating future generations of America’s military leaders to represent the best of our national ideals.”

Many of the contested tributes commemorate Lee, who graduated from West Point and later served as its superintendent before resigning from the US army. In addition to his monumental portrait, the Commission recommends that references to and a quote by him be removed from a USMA plaza. It also calls for the renaming of West Point locations such as Lee Barracks, Lee Road, Lee Gate and Beauregard Place, which honours General P.G.T. Beauregard, whom the report describes as “an ardent supporter of enslavement, secession and rebellion”.

At the USNA, the Commission recommends that Buchanan House, Buchanan Road and Maury Hall, all be renamed. The former two sites were named in honour of the Confederate admiral Franklin Buchanan, whose “efforts killed hundreds of US Navy sailors”, the report states. Maury Hall carries the legacy of Matthew Fontaine Maury, a prominent oceanographer and climatologist who “viewed African Americans as unworthy of life, liberty or the pursuit of happiness”, as described in the report. “Maury envisioned a series of vast American territories in Central and South America, where enslaved humans would produce commodity crops like cotton, rubber and sugar.”

The Commission notes that the memorialisations of Confederate figures at USNA began in 1915 during the ascendant years of the “Lost Cause” mythology, which sought to vindicate the Confederate cause and downplay the role of slavery in the war. USMA began installing Confederate-affiliated items beginning in the 1930s, accepting them “due to external pressures”, the report says.

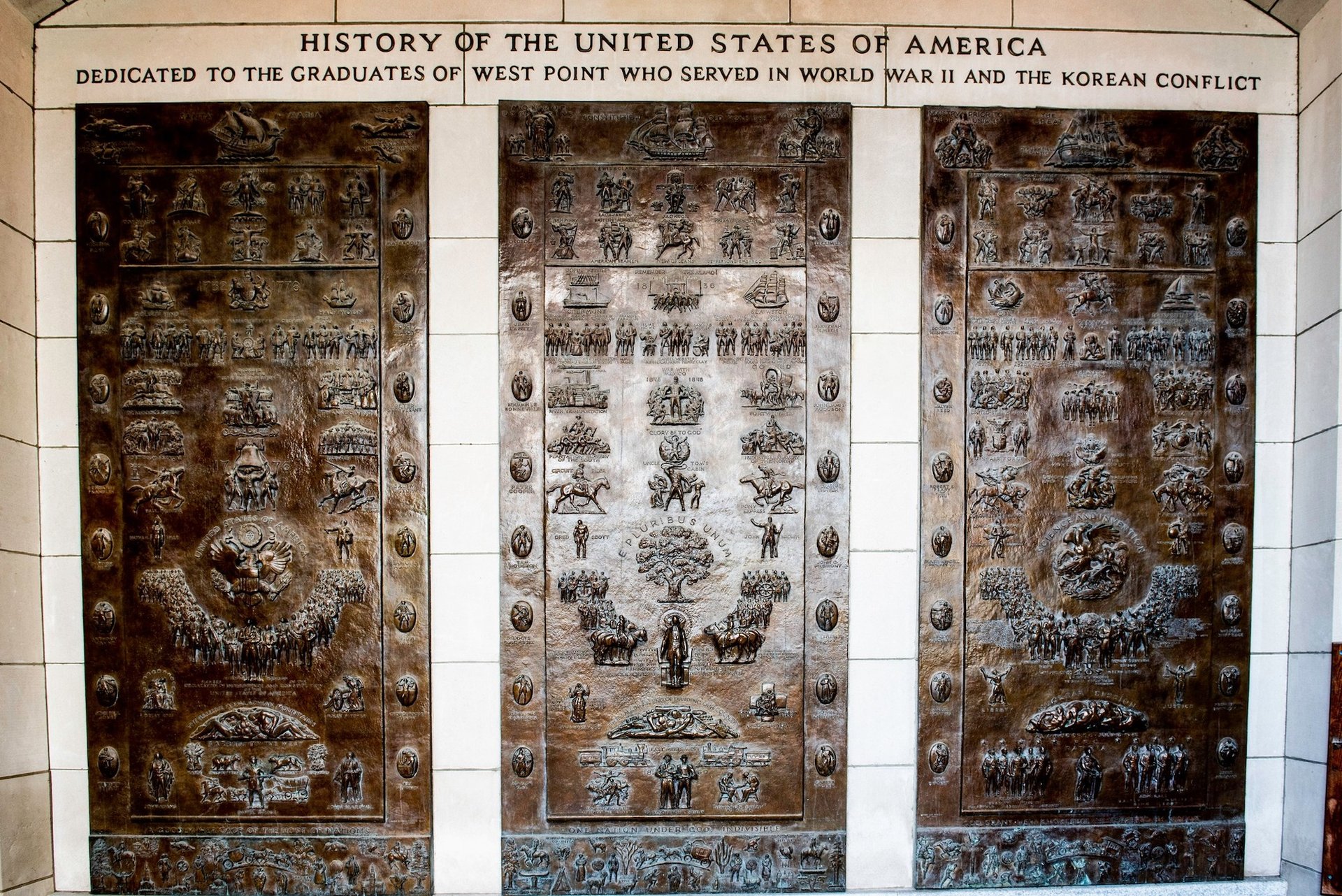

Laura Gardin Fraser's monumental triptych on the exterior of the Bartlett Hall Science Center at the US Military Academy in West Point, New York Photo courtesy West Point, United States Military Academy, via Facebook

One later work at West Point, dedicated in 1965 to its graduates who were veterans of the Second World War or the Korean War, is a triptych of plaques at the entrance of Bartlett Hall Science Center. Made by sculptor Laura Gardin Fraser, the monumental plaques feature close to 150 historical figures, with panels that commemorate several Confederate officers including Stonewall Jackson, which the Commission suggests should be modified or removed.

The triptych also features a portrait of a member of the Ku Klux Klan, which Fraser described in her notes as “an organisation of white people who hid their criminal activity behind a mask and sheet”. The Commission flags the imagery in its report, noting that “there are clear ties in the KKK to the Confederacy”, but ultimately was not able to issue a recommendation because the plaque falls outside its scope.

“The reason that we put that in there was because we thought it was wrong,” Ty Seidule, vice chair of the commission, told The New York Times. “When we find something that’s wrong, but it’s not within our remit, we wanted to tell the secretary of defence about that.”

The Commission will release a third report before 1 October that addresses remaining DoD assets. All recommendations will be sent to Congress and the Secretary of Defence, which will implement a plan by 1 January 2024.

The effort is one of several to confront Confederate legacies in the public that have emerged across the US, such as the Legacy Commission in Charlotte, North Carolina, and the Chicago Monuments Project. National debates over the fate of public monuments and other tributes to racist historical figures, from Theodore Roosevelt to Christopher Columbus, escalated after the police murder of George Floyd in 2020.

As did many similar commissions of its nature, the Naming Commission gathered public feedback on the items at USNA and USMA through discussions with elected officials and local stakeholders, from representatives of civil rights organisations and historical societies to members of rotary clubs and churches. It also created a website open to public comments, receiving more than 34,000 submissions over a three-month period. Both Academies are still reviewing their inventories, according to the report, which notes that “it is probable even more Confederacy-affiliated items will continue to be identified”.