The National Museum of Brazil (Museu Nacional-UFRJ) in Rio de Janeiro has unveiled the first phase of a phoenix project this week nearly four years after a fire gutted the historic institution and consumed most of its collection.

The museum had hoped to open one wing of the building in time for the Brazilian bicentennial of independence on 7 September but faced various financial and pandemic-related delays.

Instead, the Rio de Janeiro-based firms Velatura Restaurações and Construtora Biapó have completed the restoration of the museum’s façade, and marble statues that once flanked the museum’s roof are being exhibited in the adjoining Quinta da Boa Vista park. Replicas have been fabricated for the building to safeguard the originals.

Several other exhibitions, including a collection of minerals, will also be installed on the ground-floor of the museum and visible to visitors from the outside. The full building is now tentatively scheduled to reopen in 2027.

The fire in 2018 destroyed around 85% of the artefacts housed in the National Museum of Brazil (Museu Nacional-UFRJ). Reuters/Ricardo Moraes

The museum had been underfunded and vulnerable to fire for years. After a series of warnings, an overheated air-conditioning unit caught fire on 2 September 2018 and quickly spread throughout the 122-room building. Within two hours, the museum itself, and more than 18 million pieces in its archive, had been destroyed.

Inspectors had warned of a fire risk as early as 2004. Just months before the fire, an anonymous public complaint was submitted to federal prosecutors by an architect who identified and photographed specific hazards throughout the building.

The tragedy prompted debate on the state of cultural funding in Brazil ahead of the election of the far-right president Jair Bolsonaro, following the appointment of the former president Michel Temer, whose administrations both imposed significant cuts on the cultural budget.

The museum’s director, Alexander Kellner, was appointed to the role around six months before the fire struck. “Of course, this is not something that anyone would like to happen in their career—I will go down in history as the director of the museum that caught fire,” he tells The Art Newspaper. “But as long as my health allows I’ll work to recuperate the museum because overcoming this tragedy can perhaps be an inspiration for other struggling museums in Brazil and throughout South America.”

National Museum of Brazil (Museu Nacional-UFRJ) in 2011. Photo: Halley Pacheco de Oliveira.

Shortly after the fire, Kellner published an open letter to Brazil’s national congress and the country’s then presidential candidates calling for the government to reinforce cultural funding and further commit to reconstruction efforts. As the October presidential election looms, he hopes there will be “more gestures of goodwill from the government, and some promises of investment in culture”, because “currently there is close to zero”.

The renovation is estimated to cost around 380 million reais ($75m) but the final figure could reach around 500 million reais ($97m). The federal government has contributed around 300,000 reais ($58,000) each year. “It’s something but it’s peanuts in comparison to what we really need for the project,” Kellner says. “All the federal funding comes from tax deductions, which the ministry of education—the government—has to then approve.”

The Rio de Janeiro government has donated 55 million reais ($11m) and the Brazilian Development Bank has donated around 50 million reais ($10m); other significant endowments have come from private donors and foreign governments.

Historical layers

The São Paulo-based firm H+F Architects, led by Eduardo Ferroni and Pablo Hereñu, has overseen the interior renovation since 2020. According to Hereñu, the fire created a “violent intervention”, making visible parts of the building that would not have surfaced during a normal renovation.

Originally the home of the Portuguese slave trader Elias Antônio Lopes, the building became the residence of the Portuguese royal family in 1808 before becoming a museum in 1892. Throughout the process, it was remodeled and rebuilt and expanded several times. “Some of these layers have been hidden for more than a hundred years,” Hereñu says.

Once the renovation is complete, the architects hope the history of the building will be more visible. “We would like to make it easier for visitors to read this timeline through the building itself—to reveal the contradictions that exist here,” Hereñu says. “There were arches that were cut in the middle, windows hidden by new walls, paint covered by dozens of layers and many other elements that tell this complex story.”

When it reopens, the museum will inescapably be more modern. “We are attempting to conserve everything that survived. But, in many situations, everything was destroyed,” Hereñu says. “There will be a more contemporary atmosphere, with a mixture of elements conserved and restored.”

The National Museum of Brazil (Museu Nacional-UFRJ) under construction following the 2018 fire. Photo: Felipe Cohen. Courtesy Museu Nacional-UFRJ.

Before the fire, the museum had around 3,400 sq. m of exhibition space, within which 6,000 objects were displayed. The future museum will contain around 5,500 sq. m of exhibition space with the capacity to display around 10,000 objects.

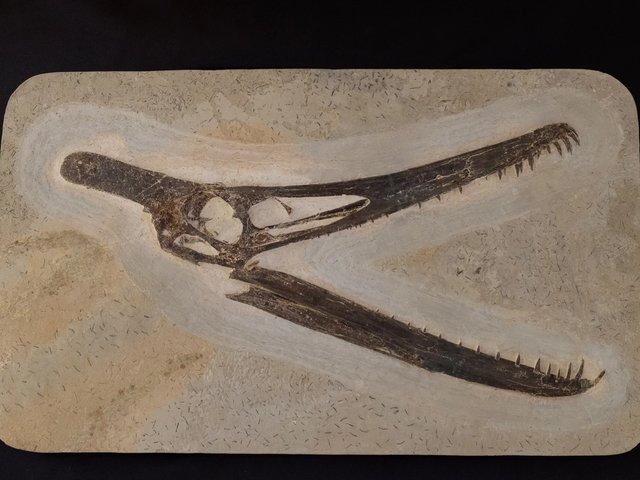

One of the most significant parts of the project is rebuilding the museum’s collection, which included more than 20 million objects, including botanical specimens, Indigenous objects, meteorites, fossils and archaeological artefacts. The fire destroyed around 85% of the collection, not including around 15% that was stored in an external facility.

The museum has a “wish list” of objects it hopes will be donated by Brazilian and foreign institutions. Significant contributions so far include a promise from Unesco to donate 140 objects in total from each of its geoparks and a collection of botanical specimens from the Amazon from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

As Brazil seeks to re-establish its cultural identity through the restoration of its most significant institution, Kellner emphasises that it “needs to deserve this new material”, and it will “only prove that we deserve the materials if we rebuild the palace with the best safety measures in place”.

Around 50,000 objects were recovered from the fire. Among the works that survived was a 12,000-year-old skull nicknamed “Luzia”, the oldest human remains discovered in South America and a cornerstone of the museum’s collection. The Bendegó meteorite, the largest meteorite ever found in Brazil, discovered in 1784 in Bahia, was also found intact.

Museum scrutinised for conflict of interest

The federal organisations that administer the museum—the Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (Iphan) and the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro UFRJ—were recently accused of “irregularities” in the hiring process of companies involved in the reconstruction project.

According to a complaint that has now reached Congress, there has been a “triangulation that could reveal an evident game of marked cards and conflict of interest that has been fueling the flames of serious suspicion of corruption” in the project.

The complaint specifically states that a technical coordinator of the IPHAN, which was in charge of providing inspection services, is the son-in-law of two consultants contracted to produce proposals and guidelines for the reconstruction process. The investigation remains ongoing.

• Listen to an interview with the museum’s director, Alexander Kellner, on The Week in Art podcast

• Read all of our coverage on the Brazil Bicentennial here