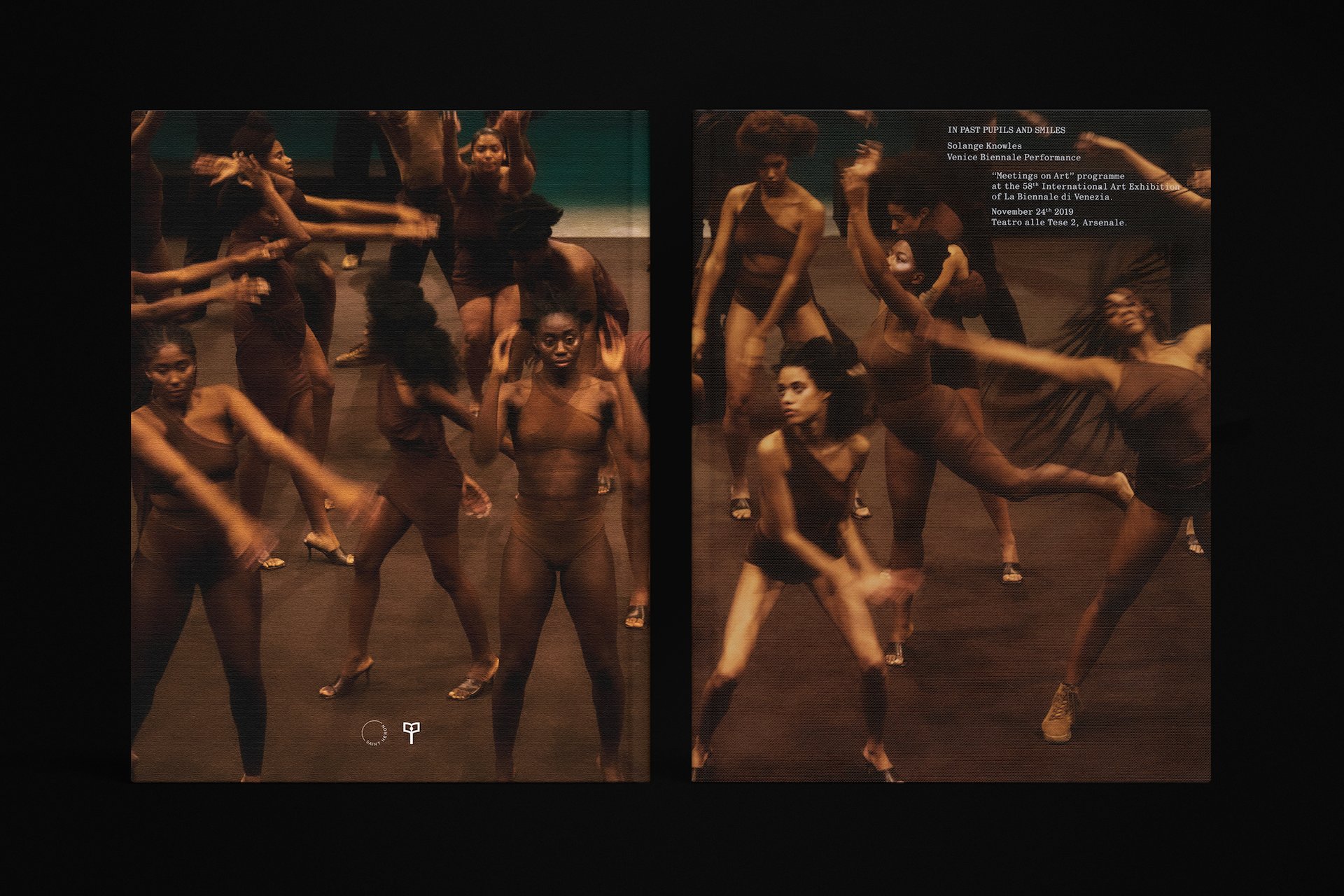

In the closing days of the 2019 Venice Biennale, the multi-hyphenate artist, musician and cultural force Solange Knowles took over the Arsenale’s dramatic Teatro alle Tese to stage her newest performance art piece, In Past Pupils and Smiles (2019). The work was performed live with musicians, dancers, singers and a group of 16 Black women dubbed “The Gatekeepers”, a troop of dancers who were invited from across Europe to participate in the piece.

For Knowles, the work was a response to a period of transition and uncertainty she likened to being in mud, hence the deep brown hue of the minimalistic set and costumes. It built on performance art pieces Knowles had debuted earlier that year, including Witness! (2019) at the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg and Bridge-s (2019), staged at the Getty Center in Los Angeles just one week prior. It also bore the influence of When I Get Home (2019), the film that accompanied her critically acclaimed album of the same name.

The front and back covers of In Past Pupils and Smiles Courtesy Solange Knowles, Anteism and Saint Heron

In Past Pupils and Smiles—produced by Arts Council England and officially part of the Biennale’s “Meetings on Art” series curated by Delfina Foundation director Aaron Cezar—was only publicly staged once, but photographs of that performance and another staged strictly for documentation purposes are the focus of a new book from Montreal-based publisher Anteism out on 23 August. Never one to only have one project in the works at a time, she is also composing her first ballet score, which will debut at the New York City Ballet's Fall Fashion Gala on 28 September.

Here, Knowles discusses the genesis of her Venice Biennale piece, how its meaning has evolved for her in the very tumultuous two years since its debut and the performance art forebear who informed how she documents her work.

The Art Newspaper: You have said of In Past Pupils and Smiles that it was “a moment of mourning” and “a moment to express how much grief comes from loss”. Looking back on it after more than two years of enormous (and ongoing) loss and grief, how has your understanding or appreciation of the piece changed?

Solange Knowles: I think the process of grief is so specific to our own individual stories, but the collective grieving we’ve been doing the past couple of years…I think we don’t and won’t know the effects of that for a long time. I began grieving a lot of loss in my own life prior to this piece coming out, really reflecting on the things I needed to scream about, throw fits about, neck roll about, and this show was sort of my way of saying that I won’t always have grace and give grace, and that is OK.

When we go into the afterlife, our family and friends have a “wake” to view the body, and to give a moment to respond to the overwhelming feeling that comes with loss. This show was in some way my own wake—viewing my own body and the bodies of women who share in my grief. Sometimes at service, you can hold it all together until the music starts. I felt like from the minute those first sirens hit, it became a calling to let it out. For the performance to be the space where there was no need to hold it together. So many Black women I know began to sit with our traumas and began doing deep internal work within ourselves during this time, and it will be interesting to see generationally what that looks like for all of us. I wish peace for all of us in these new awakenings.

A photograph of In Past Pupils and Smiles (2019) by Solange Knowles from the new book on the project Photo by James Mollison, courtesy the artist, Anteism and Saint Heron

For the performance, you invited 16 Black women from across Europe—The Gatekeepers—to participate. How did their experiences and perspectives inform and shape the performance? How did your interactions with them affect how you saw the piece?

I named this piece In Past Pupils and Smiles to honour the daily interactions that I have with Black women that have saved me. There’s a certain eye contact or smile that we give to one another when we feel the most seen, heard, protected and acknowledged. I hold those moments so sacred.

I find that a lot of racist shit happens when you travel—in the airports, the check-in counters at hotels, restaurants, places away from home—when you’re already so vulnerable. The looks I get from Black women in these environments make me feel so embraced in those moments. Those glances hold me. I know they know the story without having to say one single word. Inviting these women into the show was a pivotal moment in the process. The piece became an offering for them.

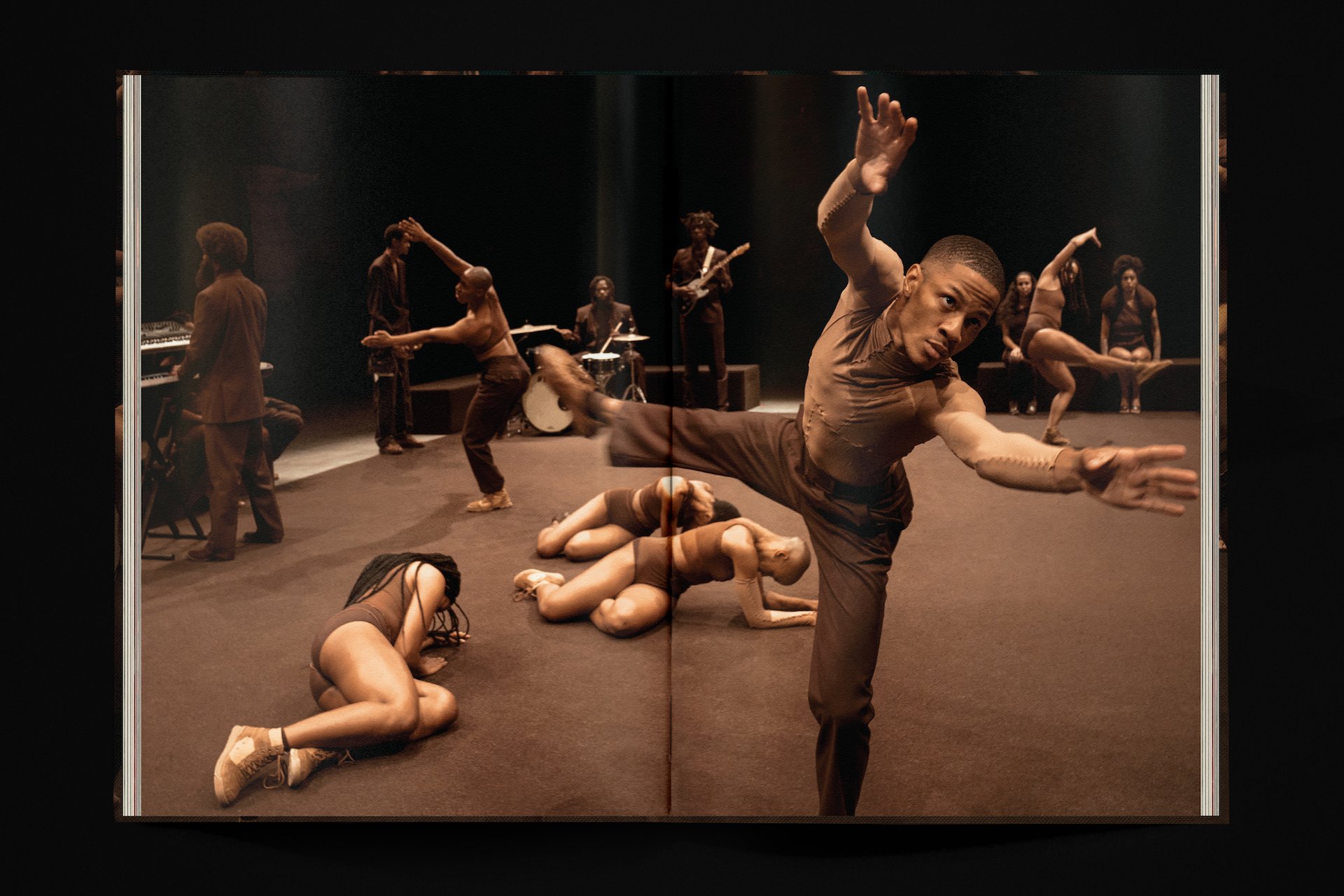

Performers in Solange Knowles's In Past Pupils and Smiles (2019) Photos by James Mollison, courtesy the artist, Anteism and Saint Heron

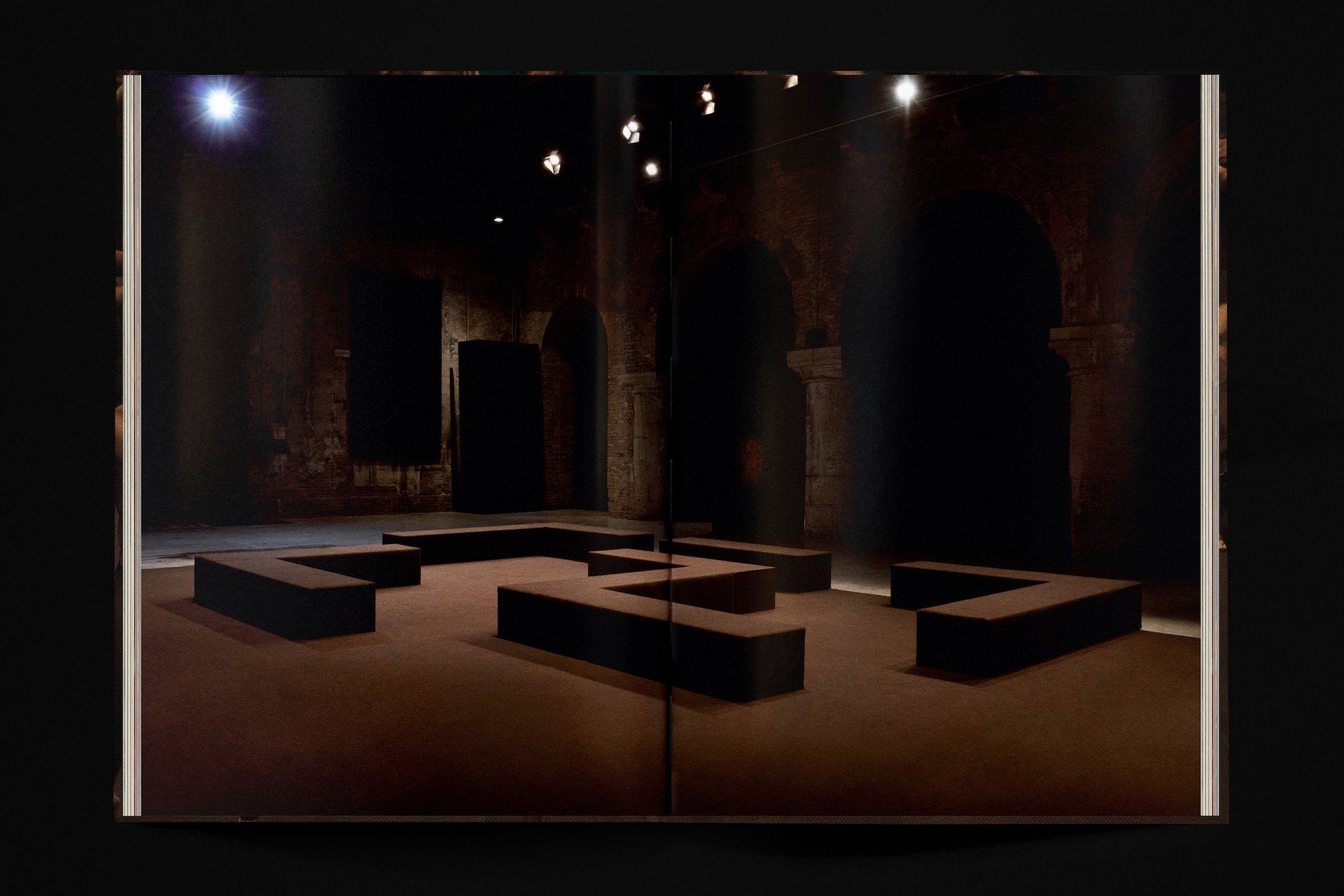

Before gatekeepers became folks who designed spaces to keep us out of—spaces that gatekeepers have decided we don’t belong to—there were stories and scriptures of gatekeepers of the temples. They were the backbone of the temple and all of the ways it functioned. I designed scenography to keep the space centred, to build an energy force in the square. These women were keepers of that energy and it was reciprocated back to them. We protected one another. I remember the night before the first performance, I asked all of the performers to only make eye contact with the women and one another—never anyone outside the square viewing the piece. This insured the intentionality of the offerings. We performed only for these women and when it was over we all had said so much to one another without saying a single word.

Venice is such a symbolically charged place, both in its current precarious existence at the forefront of climate disaster, and in its history as a centre of European culture and trade, many of whose riches were gotten through colonisation and exploitation. How were you thinking about the symbolic weight of this site while developing In Past Pupils and Smiles?

World-making has been at the centre of my work for so long, so when I step into any space I am considering the history, the symbology, the past, present and future, but I am mainly focused on the world I can create within the space. In this particular piece, the historic architecture weighed heavily on me. I gave a lot of consideration to the columns, which I have architecturally leaned into in past works. I decided to ignore them for this piece. Ignoring the architecture, and in continuing the language of my film When I Get Home (2019), this was a time to create my own coliseum. This was a time to dig in the soil and to get my hands and feet in the mud. I really honed in on ways I could bring that feeling to life.

A photograph of the stage set for Solange Knowles's In Past Pupils and Smiles (2019) Photo by James Mollison, courtesy the artist, Anteism and Saint Heron

There was an eeriness about the floods that were happening while we were there. My costume designer was literally carrying the costumes in suitcases over her head in knee-high water on the sidewalks. We had just played the Getty and weeks before the show there were forest fires. Mother Nature had definitely been trying to get our attention during these shows.

Performance art, especially when it’s performed at destinations like the Venice Biennale, often reaches more viewers through documentation (whether videos and photos, or books); as you were working on In Past Pupils and Smiles, how did you think about the piece’s afterlife in media and documentation, and how did that influence the performance?

I think about Senga Nengudi’s Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978) and the images from that piece, and how much they have impacted me, how much they have informed the way I see the world and performance art. Without those images, my entire context for performance art would be different. I remember them closely when I am considering how and why I document my own work. I’m leaving these images and text behind for a future generation.

It’s important for the work to live on long after I’m here. It’s important to make timeless choices because of that. When we documented these images I had the photographer capture while we were performing, and then again performing the piece with no audience. It shifted our posture, our eye contact, the way we rested our hands. I love looking through the book and being able to identify which images were from each take.

Performers in Solange Knowles's In Past Pupils and Smiles (2019) Photo by James Mollison, courtesy the artist, Anteism and Saint Heron

In Past Pupils and Smiles followed other pieces you staged in 2019, Witness! and Bridge-s. How did your experiences with those earlier pieces inform your approach with In Past Pupils and Smiles? And, in turn, how has the experience of developing, rehearsing and performing that piece in Venice (and revisiting it for this book) influenced how you’re thinking about future pieces?

All of my work evolves in the next piece. I am constantly taking themes I’ve explored in past shows and using the next piece to dig deeper, explore more [and] ask new questions. Witness! really informed the musical landscape for In Past Pupils and Smiles. It was sort of my introduction to working on new musical compositions in this space and so it’s been wonderful to see the evolution of the sounds and language in the music. I developed a counting system for these pieces that has really laid the foundation for how I compose, so those early works really helped inform how I work on performance pieces.

Bridge-s and In Past Pupils and Smiles have a lot of similar parallels since they use the same choreographers and dancers. However, where Bridge-s looks to the light, and really embraces architecture, In Past Pupils and Smiles embraces the darkness and creates its own architecture. It becomes theatre.

As I look to the future, I’m excited to find new homes for the pieces. They still have a lot of life left in them.

A photograph of In Past Pupils and Smiles (2019) by Solange Knowles from the new book on the project Photo by James Mollison, courtesy the artist, Anteism and Saint Heron

Solange Knowles, In Past Pupils and Smiles, Anteism, 188pp, $55, publishing 23 August