• Read about the museums shortlisted the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2022 here

The towering red-brick building, Derby Silk Mill, that houses the Museum of Making is itself a key piece of history. It is on the site of a silk-throwing mill built in 1721 by brothers John and Thomas Lombe. Powered by water from the River Derwent, it once produced thread on an unprecedented scale. Operating 50 years before Richard Arkwright set up his famous cotton mill upriver at Cromford, it is regarded as the world’s first fully mechanised factory.

Three hundred years after the mill was born, the current 1910 building came back to life in May 2021 as the Museum of Making, one of three sites run by Derby Museums. A decade-long £18m redevelopment brought about “a complete transformation”, says Tony Butler, the trust’s executive director. The mill previously housed Derby Industrial Museum from 1974 until 2011, when the city council mothballed it. Visitor numbers had dwindled and the displays were outdated, Butler says, rooted in “a ‘great man’ history of industry” and a narrative of “unique British genius”.

The stars of the museum today are its eclectic objects, united by their origins in Derby and Derbyshire. Exhibits include a miniature engine run on a single human hair, the classic cast-iron red post box, locally made video game Tomb Raider and a beloved model railway (activated twice a day in its own dedicated room). The galleries exude pride in the region’s manufacturing prowess but do not shy away from the dark side of the industrial boom. Wall texts reference the environmental impact of burning fossil fuels, the British Empire’s reliance on slave labour and the “intolerable conditions” faced by workers at the mill, including children as young as eight.

True to its name, probably the biggest innovation is the way the Museum of Making has empowered audiences to make and do. Unlike the “static, didactic” museum of old, “learning and activity are built into the DNA of this space”, Butler says. The belly of the building houses learning studios and a workshop where paying members can access a kiln, a furnace, woodworking benches and laser cutters, among other tools. A driving force behind the redevelopment has been the idea of “bringing manufacturing back to the site of the world’s first factory”, Butler says.

At this 300-year-old site you can find out about Derby’s pioneering industrial history © Emli Bendixen/Art Fund

Local makers and residents have had a hand in designing the museum from its inception in 2011. When the public were first invited to suggest ideas for the silk mill’s future, “it became clear that people felt strongly about the heritage of manufacturing in the city but they wanted it to be relevant to their lives today,” Butler says. Even before major funding was secured from National Heritage Lottery Fund, community groups were involved in prototyping sessions with the architects of the redevelopment, Bauman Lyons. “We’d have events where people were thrashing out potential designs for galleries using cardboard boxes and string.”

By popular demand, objects are organised by material rather than chronology in the Assemblage, a sprawling open-storage space housing the bulk of the collections. Visitors are free to roam without curatorial direction beyond the basic placards indicating “wood”, “metal” or “textiles”. The groaning shelves have the air of an antiques shop or a warehouse, displaying many items outside the usual Perspex cases. There were some grumbles from traditionalists, Butler admits, but most visitors “like the idea of self-discovery and being able to rummage”.

A few of the sceptics were later converted into museum volunteers, he adds, joining the “phalanx of people” who helped out in the years before the opening, moving collections into storage and even fabricating bespoke object cases using the workshop’s facilities.

It is this hands-on civic spirit that Butler hopes will convince the Art Fund judges to give the Museum of Making the prize. “I think we have shown that you can make a museum from the ground up,” he says. “And that by taking a human-centred approach we are able to build a community around the joy of making.”

How does the museum anticipate spending the £100,000 prize money if it wins? Most likely, it would mean a boost for its interdisciplinary learning programme, the Institute of STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Maths), sponsored by Rolls-Royce. Connecting the dots between Derby’s industrious past and its high-tech future, the scheme aims to inspire budding technicians and creative entrepreneurs at “every school in the city”, Butler says.

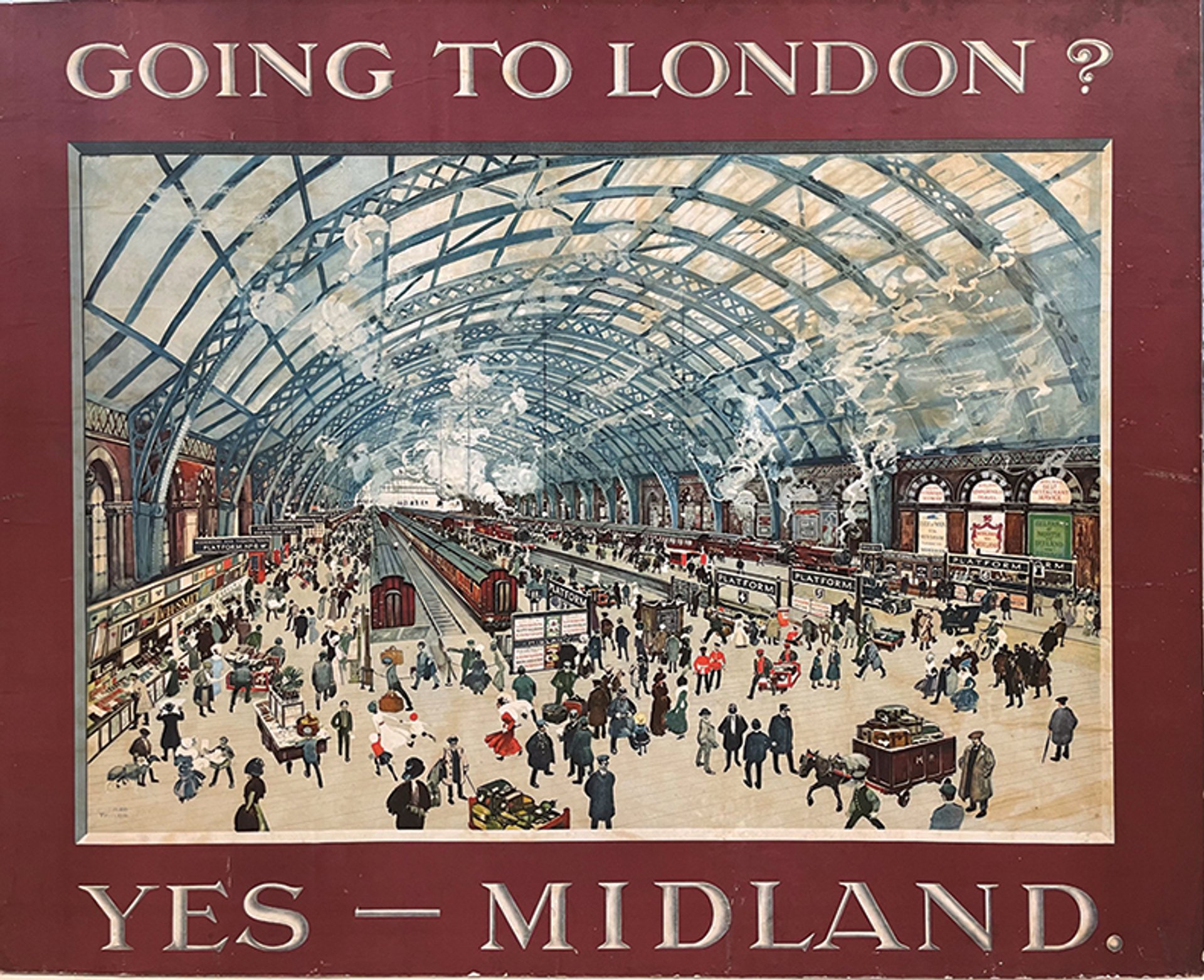

Advertisement poster by Fred Taylor (around 1910) Courtesy of Derby Museums

Must-see: Advertisement poster by Fred Taylor (around 1910)

“Obviously the massive, seven-tonne Rolls-Royce Trent jet engine is the legendary object in the museum’s Civic Hall but I also like this poster of the Midland Railway up in the Railways Revealed gallery depicting St Pancras station in around 1910 (inset, below). In the artwork, there’s the canopy of St Pancras, which was made in Derby. The iron roof frame was done by Andrew Handyside’s foundry in the city, most of the locomotives and rolling stock would have been made in the Midland Railway Locomotive Works in Derby and many of the people would have probably been [travelling] from Derby as well. So the picture is of a landmark station in London, but everything was made in Derby.”

Tony Butler, executive director of Derby Museums