Almost a decade ago, a woman bought a painting, Bathing Machines, Aldeburgh, for £100 at a sale in Oxfordshire. It hung on her wall for a year until she died, when her widower sent it as part of a consignment to a regional saleroom. It sold there for £265,000.

It turned out that the artist was Eric Ravilious, known during his heyday in the late 1930s and early 1940s for his engaging woodcuts (an early work is the image of two gentlemen cricket players that still graces the cover of the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack), a popular book of traditional high street shop fronts and, latterly, for his sublime watercolours—timeless landscapes of freshly ploughed fields, undulating hillsides with ancient chalk figures—and work from his time as war artist of the Royal Marines.

Almost 80 years after Ravilious’s untimely death—his plane disappeared off the coast of Iceland while observing a rescue mission in September 1942—his work is now widely revered and is gaining renewed attention in a documentary, Eric Ravilious: Drawn to War, directed by Margy Kinmonth and released in British cinemas in July.

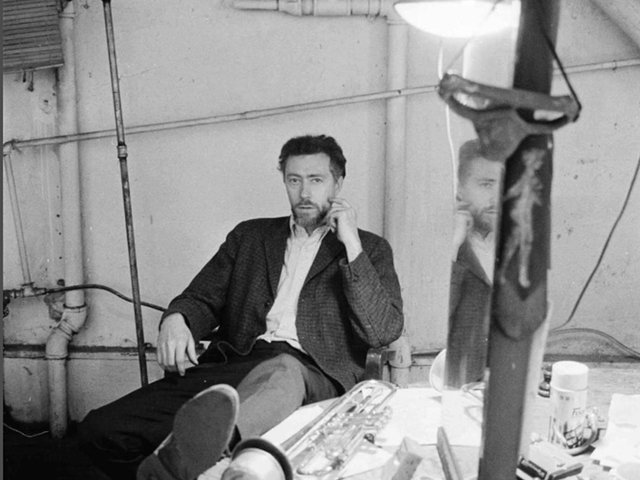

Ravilious with his wife and fellow artist, Tirzah Garwood. The couple had three children, one of whom, author Anne Ullmann, appears in the film © www.foxtrotfilms.com

Struggling artists

On the rare occasions when his paintings or ceramics come up for auction—he was commissioned to produce several ranges for British ceramics firm Wedgwood—they achieve prices that he could not have conceived of during his lifetime (shortly before he died, the Foreign Office offered him £20, around £650 today, for four original sketches). After Ravilious married the painter Tirzah Garwood (who had been his student in Eastbourne), they were always short of money. They lived in a succession of houses, first near the Thames in Chiswick, not far from Acton, west London, where he was born in 1903, then in Sussex and Great Bardfield, Essex—near the graphic artist Edward Bawden, who was best man at Ravilious’s wedding, and his wife Charlotte. Not long before his final mission, he wrote to Garwood, asking if she could possibly send him a pound to tide him over, as his war-artist’s wage did not quite stretch to pay day.

At the time of his death Ravilious, who had studied alongside Henry Moore under Paul Nash at the Royal College of Art in London, had only had two solo shows. But his work, influenced by Nash and earlier artists including Samuel Palmer, but in a class of its own, had caught a particular mood, as well as the eye of Kenneth Clark, who founded the War Artists’ Advisory Committee.

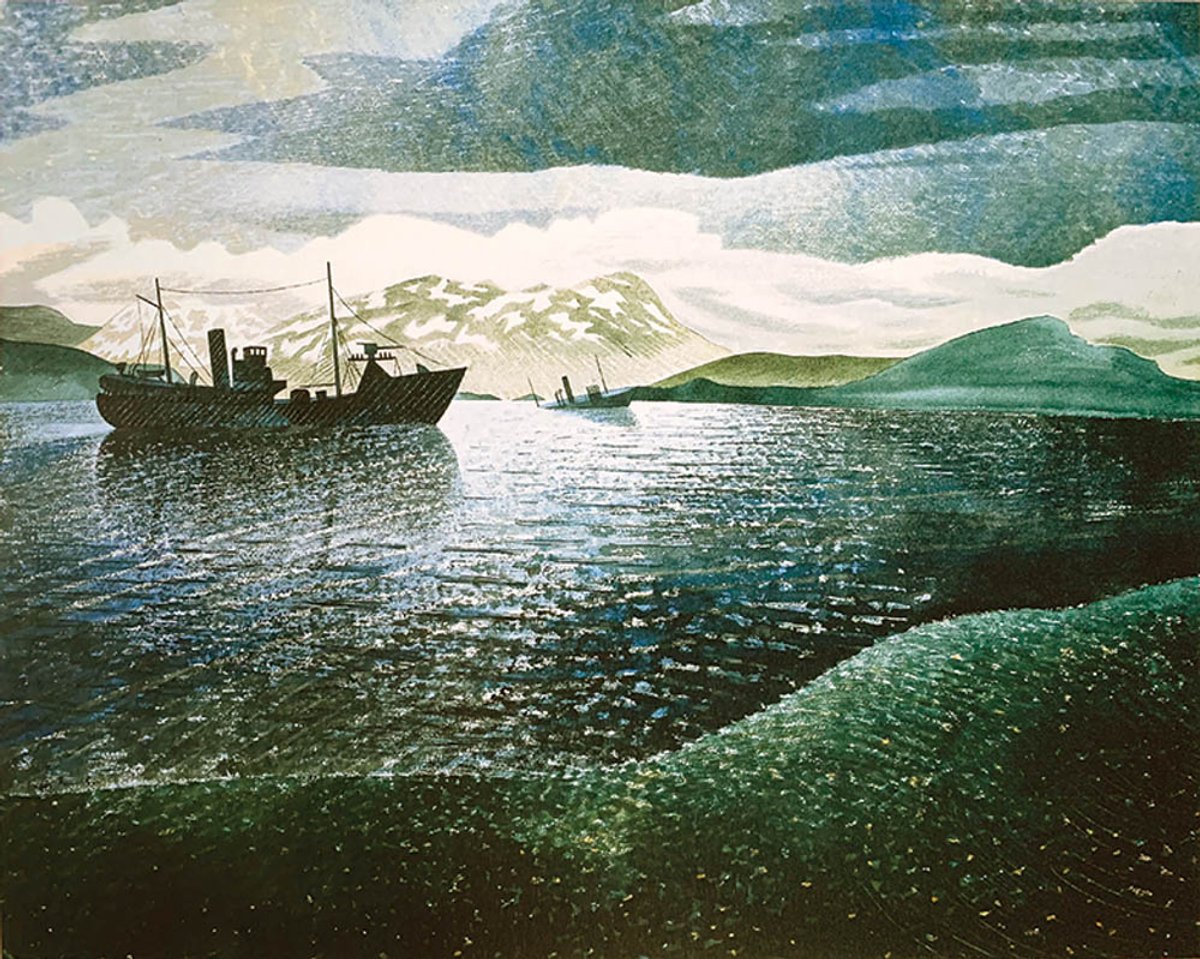

In Kinmonth’s documentary, other admirers of his oeuvre speak of Ravilious’s skill at capturing a moment in time. The writer Robert Macfarlane, referring to the painting Midnight Sun, which depicts a depth charge ready to be dropped into the sea, describes “classic Ravilious” as when “everything is in potencia, at once profoundly serene and profoundly disturbing”.

Just as Ravilious’s country scenes often lead the eye up a path stretching into the distance, Kinmonth takes us on a journey to learn how Ravilious developed the art of observation across his life—from watching the planes heading to war as a small boy to trying to recreate the light of a night-time explosion on the water off the shores of Norway, when the sun shone for 24 hours a day.

Drawn to War tells Ravilious’s story very much in the artist’s own style. Kinmonth, whose previous film focused on the Russian avant-garde, assembled a “look book” of his life and works that won the approval of Anne Ullmann—his last surviving child and the author of several works on her parents—who appears in the film. It paints the trajectory of the artist’s life using a similar muted palette—the cinematography is pitch perfect—with previously unseen letters voiced by the actors Freddie Fox and Tamsin Greig and reconstructed works by the artist and engraver Robin Mackenzie.

Labour of love

Kinmonth says the making of the documentary was “a labour of love”. Filming took place on location in the UK and Portugal during the pandemic, with “more challenges than we’d planned”, she says. Contributors range from the artist’s granddaughter, Ella Ravilious, a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, to James Russell, who curated the major Ravilious survey at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London in 2015, and superfans like playwright Alan Bennett and artist Grayson Perry. Perry praises Ravilious’s virtuosity—“you don’t get a second chance with watercolours”—and ability to make “great work out of such basic subject matter”.

From his studio in Portugal, artist Ai Weiwei ponders Ravilious’s obvious enthusiasm for his final commissions, suggesting that in his excitement at producing what he thought was some of his best work, while recording life on the submarines and then destroyers off Iceland, the artist was all too aware of the risks of the role. But, Ai tells Kinmouth: “When you are so drawn into conditions, you forget the danger.”

The vividness of Ravilious’s situation sometimes drove him to stay up all night painting. “The seas in the Arctic Circle are the most intense blue you can imagine,” he wrote to his wife. “Almost cerulean.” The intense commitment to his work may also have been practical; a bid to make up for the loss of some of his work that was sunk in the Atlantic while on board a ship bound for a UK government propaganda exhibition in South America. “Being a war artist wasn’t a soft option,” says Alan Bennett in the film. “Painting was his active service and he gave his life for it.”

Seven years after he went missing, Garwood died of cancer, leaving three young orphans who grew up largely unaware of their father’s legacy. It wasn’t until the 1980s that Ullmann began a quest to find out more about her then largely forgotten father. She wrote to Bawden—who was still in Great Bardfield—and received what she describes in the documentary as “a very nice letter back”. It revealed that Bawden had kept a trove of Ravilious’s paintings under his bed for 40 years. That was the start of his rediscovery; Kinmonth’s film can only help this great artist gain even greater prominence.

• Eric Ravilious: Drawn to War is in UK cinemas from 1 July. Visit dartmouthfilms.com for more information