Over the past 70 years, Queen Elizabeth II’s wardrobe was concerned not with fashion, but with dress. The two are different. She treated her clothing as a tool of work, ensuring comfort and appropriateness, and affording visibility, propriety and immutability. She also deployed it not only to connect with her people but also as a strategic weapon on the battleground of national and international diplomacy.

Dress is a serious business, something that Elizabeth II's predecessor Elizabeth l understood completely. One only has to look at the 1600 “Rainbow” portrait of the all-seeing, all-hearing Virgin Queen—in the collection of Hatfield House—her mantle embroidered with ears and eyes, to appreciate this messaging at play. Both Elizabeths, though born four centuries apart, set forth into battle, like medieval knights, under their own blazon, their coat of arms, their own dress code, instantly recognised in the field and from afar by their subjects. Elizabeth II’s banner has been block colour, and her blazons, whether as embroidered symbols or pinned brooches, delivered messages.

She deployed [dress] not only to connect with her people but also as a strategic weapon on the battleground of national and international diplomacy

The construction of the Queen’s virtually unchanging image, a brand as distinctive as Coca-Cola, was the work of many minds and many hands. Having made a close study of the history of the constitution under her private tutor Henry Marten, Vice-Provost of Eton College, a constitutional scholar, the Queen was steeped in the art of monarchy.

The armoury of her soft power, the visual message communicated through dress, was translated and amplified by her chosen couturiers who were all British—in succession, Norman Hartnell, Hardy Amies, Ian Thomas and Stewart Parvin— and through her trusted dressers, the most recent, and of 25 years standing, being Angela Kelly. Her team understood the rules of engagement.

Amies, a decorated Second World War intelligence officer who served with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) Belgian sector, drew upon military tailoring. He may not have been innovative—that was not his mission—but he was effective.

I sometimes discussed Amies's royal brief with him. It included such strictures as the size of a hat brim, limited so that the Queen could be seen by her people; hems weighted to ensure propriety on windy days (her dressing department even included an electric fan used to test-run diaphanous fabrics); dresses rather than skirts so that no rearranging of garments was required as she stepped out of a vehicle; zips rather than buttons to facilitate up to five changes of clothing a day; washable, 15cm-long white or black cotton gloves from Cornelia James, and of great relevance, comfort—as a working woman, she was often on her feet all day. Angela Kelly, who coincidently has the same size 4 feet, would break in the royal shoes.

The Coronation Dress, designed by Norman Hartnell and worn by the Queen as one of several layers of vestments during the service at Westminster Abbey on 2 June 1953 Royal Collection Trust/All Rights Reserved

The Coronation robe, 1953: an embroidered signal of the importance of the Commonwealth

One of the first examples of the Queen's coded messaging was the robe she wore at the Coronation on 2 June 1953. It was originally designed to be embroidered (in silk, silver and pearls) with the Tudor rose, the thistle, the leek and the shamrock, in honour of the United Kingdom of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. On seeing the preparatory drawings for the gown by Norman Hartnell — who had consulted the Garter King of Arms on symbolism—the Queen made a politically crucial addendum. Hartnell had omitted any reference to the Commonwealth and so the four UK flowers came to be garlanded with those of the Commonwealth, including the South African protea and the Australian wattle flower, in acknowledgment of their importance.

The Queen wore a block colour dress and coat for Prince Charles's investiture as Prince of Wales at Caernarvon Castle, 1 July 1969. The quasi-medieval helmet echoed the ancient honour and its small size allowed her face to be seen. Obligatory matching umbrella during a damp summer PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

The investiture of the Prince of Wales, 1969: using Sixties style to be seen

Looking back over the decades, it is remarkable how the Queen negotiated the Sixties, a period of dramatic sartorial change. She cherry-picked the elements that served her purpose, alive to their connotations; freedom of movement but not from propriety, a whiff of youthfulness but not of irresponsibility, a nod to relaxation but not to disorder.

In fact, it was in this decade that she honed her abiding image and displayed a reassuring image of permanence and steady, bright immutability. Her hems did rise—though never higher than the upper kneecap and not until the end of the decade, by which time most fashionable hems had dropped to the ankles. Hers perhaps reached their shortest in 1969 at the investiture of the Prince of Wales.

From the 1960s the Queen increasingly mixed contemporary block colour—the better to stand out in a crowd—with her traditional brooches. Pendant corgis were added when off-duty Anwar Hussein/Alamy Stock Photo

Block colour and brooches: a traditional take for the age of colour television

In the 1960s, the Queen enthusiastically adopted triple gabardine, a durable, firm and hardwearing fabric, that was tailored so simply from 1964 by André Courrèges, Pierre Cardin and Yves Saint Laurent into boxy jackets, A-line skirts and shift dresses. They were imitated soon after that by her own couturiers, but the placing of a regal brooch on the shoulder served as a reminder that some traditions are never vanquished.

This was also the decade in which bright, plain colour—tomato red, cerulean blue, Wedgwood blue, mint green, daffodil yellow—was exploited, so that the Queen stood out in a crowd, but also as a tool of the televisual age. The BBC and ITV launched colour right across the schedule in 1969.

Only once did she wear trousers on an official engagement—in the Sixties. It was deemed a failure which she did not repeat

She never favoured the fragile, ephemeral, informality of hippy dress. Her hair remained perfectly coiffed, reasonably short and under control. Alert to messaging, alive to how her clothes had to perform, she used the qualities of the early 1960s to serve her purpose, while those of the late 1960s would have undermined it. And only once did she wear trousers on an official engagement—in the Sixties. It was deemed a failure which she did not repeat. Though her sister, Princess Margaret, loved to play with fashion, the Queen was held back from its wilder shores by duty and a lack of vanity. Image control has been everything.

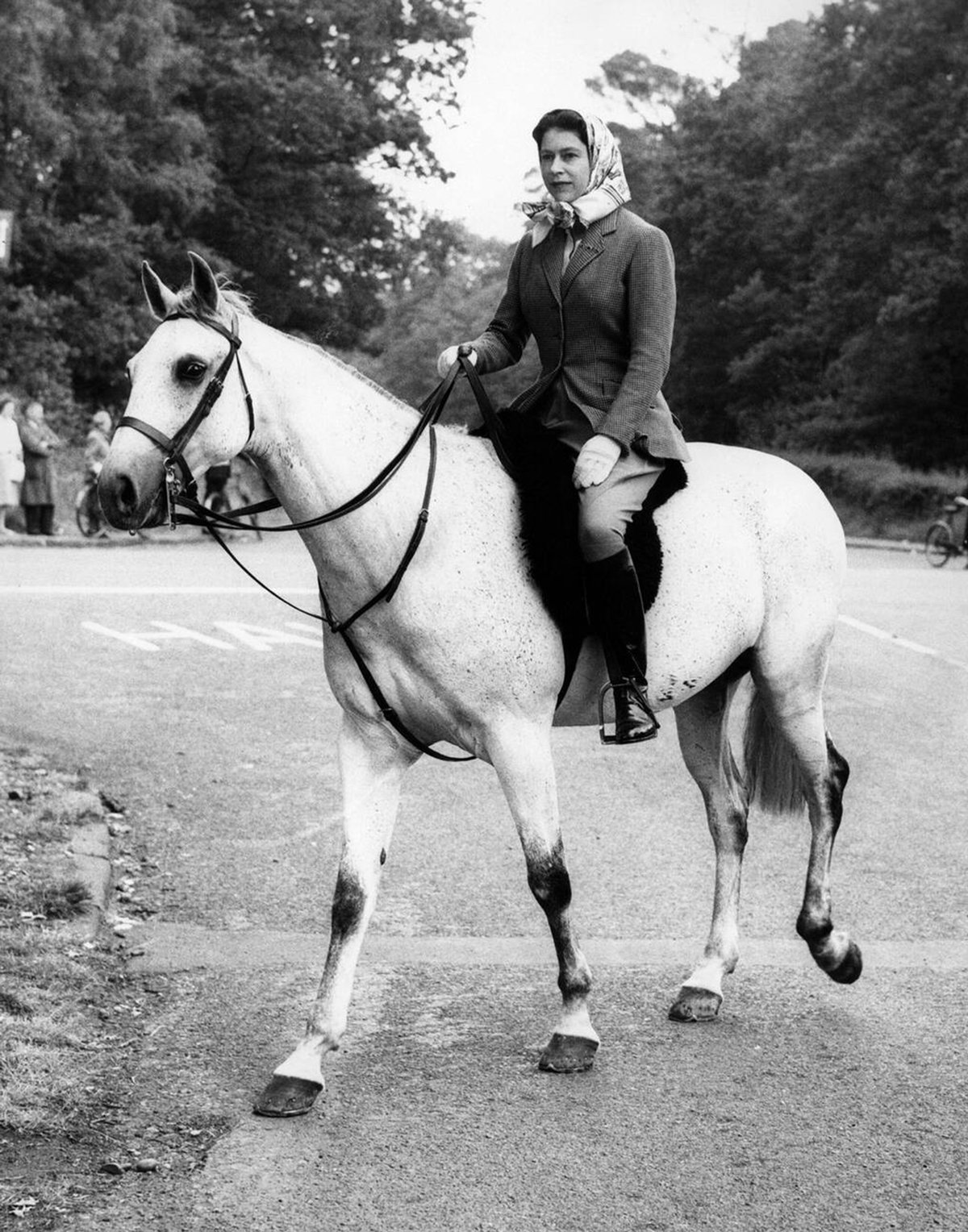

A taste for hacking jackets: the horse-loving monarch at her most British

Off duty, the Queen was at her most British and regal. Aristocratic life in Britain focuses on the countryside and field sports: riding, shooting fishing, and windswept, impractical picnics. Classic British all-weather gear from Aquascutum, Burberry or Barbour is zipped up over cashmere twinsets, redoubtable tweed skirts or jodhpurs and hacking jackets, always accessorised by that triple strand of pearls given to her by her father, King George VI.

An abiding televisual image is of her gait, full of direction and purpose, shod in stout brown lace-ups encircled by her beloved corgis. Her only nod to clothing manufactured abroad, the Hermès scarf, is, of course, the product of a company founded on equestrian saddlery. It is no coincidence that a recent photograph of Elizabeth taken to celebrate her platinum jubilee showed her standing against budding magnolias, holding the reins of a pair of grey (platinum) fell ponies. Interestingly, she wears a Loden caped coat, the traditional garb of the German upper classes. She was, after all, of the Hanoverian line.

The Queen with President Donald Trump, at Windsor Castle during his June 2018 working visit to Britain. She wears the brooch that her mother wore at George VI's funeral in 1952 Official White House Photo by Andrea Hanks

Message in a brooch: tenderness for Covid victims—and a coded prod for Donald Trump?

In June 2018, avid royal watchers decoded the Queen's use of a trio of brooches—as if they were an epée, foil and broadsword—for President Donald Trump’s working visit to Britain. On Day 1, a modest flower, a gift from his rivals, the Obamas; on Day 2, the sapphire snowflake given to her by the Canadian people, a country Trump derided; and on Day 3, a brooch habitually worn during mourning (and by the Queen Mother at George VI's funeral in 1952).

But the language of her dress could also communicate tenderness, such as the turquoise brooch, representing protection and hope, pinned to her shoulder as she broadcast a message of encouragement during the Covid-19 crisis in April 2020.

Clothes that abhor chic and showing-off

I remember being struck by Barbet Schroeder’s 1985 film, A Reversal of Fortune, the story of the unexplained coma into which the American socialite Sunny von Bulow had fallen. It was the clothes. Whoever had styled it really understood how the very privileged dress. They dress down, discreetly, comfortably. They have nothing to trumpet, their confidence is virtually impregnable.

Of course, it was the supremely talented costume designer Milena Canonero who had worked on the film, communicating that for members of this rarefied society, clothes serve them, and not vice versa. Durable tweeds, timeless camel and pearl-grey cashmere, darned and repaired favourites, jewellery with provenance, attire to allow the doing-of not the showing-off—these are their signatures. Not for them the branding of high fashion which is so recognisably stamped with a designer’s hand and the catwalk’s vintage.

As Amies said of the Queen when talking to the Sunday Telegraph in 1997, "There's always something cold and rather cruel about chic clothes, which she wants to avoid." She conjured a warm munificence instead.