A British delegation at an intergovermental meeting in Paris apparently dismissed its own government’s initiative to discuss the restitution of the Parthenon Marbles with the Greek culture minister, Lina Mendoni.

Speaking to international delegates assembled in Paris for the latest session of Unesco’s Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property (ICPRCP) last week, a senior official at the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) said that the government does not have the authority to discuss the fate of the ancient sculptures.

Participants at intergovernmental meetings represent their respective governments and it is highly unusual for them to diverge from their government’s stated intentions, so the comments suggest that, behind the scenes, British officials are struggling to articulate a coherent policy on the Parthenon Marbles in the face of increasing pressure for restitution.

Who owns the Parthenon Marbles?

The revelation that British officials will soon meet with Lina Mendoni to discuss Greece’s claim for the sculptures’ restitution was made by Unesco, on the eve of its ICPRCP meeting.

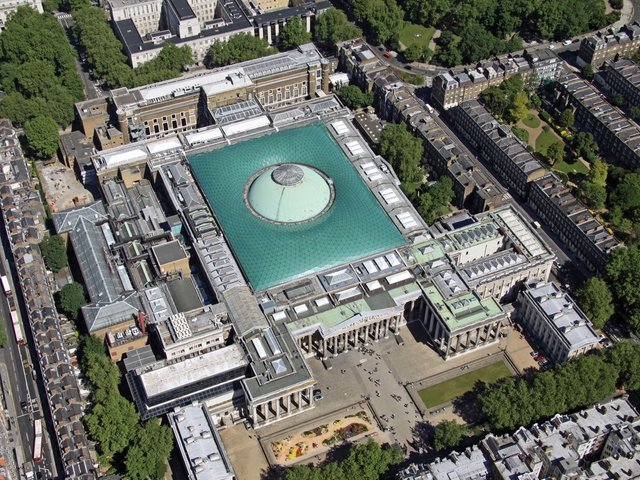

In a preliminary report for delegates, the Unesco secretariat noted that it had written to Britain and Greece in March “requesting information and proposing to facilitate dialogue” on the Greek claim for restitution of the Parthenon sculptures held by the British Museum in London, which was first submitted to the ICPRCP 40 years ago.

In its response on 8 April, “the United Kingdom informed the Secretariat of its suggestion to organise a meeting between the Greek Minister of Culture, Lina Mendoni, and Lord Parkinson, [Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the Arts].” This suggestion was sent to Mendoni on 29 April and “immediately accepted; a meeting between the parties is about to be arranged”, the Secretariat wrote.

But at the ICPRCP meeting itself on 18 May, just a few weeks later, Helen Whitehouse, the deputy director of museums and cultural property at DCMS, told delegates that the sculptures are legally owned by the trustees of the British Museum, implying that all decisions about their future are their responsibility. “It is not for the UK government to enter into discussions on the future of the Parthenon sculptures with the Greek government,” she said.

In the discussion afterwards, numerous delegates pointed out that Whitehouse failed to explain that it is precisely the British government who would need to introduce the necessary legislation to allow the sculptures’ return to Greece. (For its part, the British Museum says it is unable to return the Parthenon sculptures without a new law). Expressing frustration at this seemingly endless passing of responsibility between museum and government, the Venezuelan delegate called on Britain to stop this “game of ping pong”.

“Why won’t the UK change the law?” the Greek delegation asked. The British declined to answer.

Eighteen other countries intervened in the discussion, all voiced support for the Greek claim. None backed Britain. The Indian delegate noted that the longstanding unfulfilled claim for the return of the Parthenon Marbles is “a testimony to all that is unjust and unfair in the issue at hand” and called for “the sculptures’ return to their rightful place in Greece at the earliest opportunity”.

“What’s important about the Unesco proceedings is they show how increasingly isolated the UK is internationally,” says Professor Dan Hicks of Oxford University, who is a prominent campaigner for restitution.

The DCMS confirmed that a meeting between British officials and the Greek minister of culture will take place but denied that the government has agreed to new talks on the restitution of the ancient sculptures: “The UK government has not agreed to formal talks about the Parthenon Sculptures. While we are always happy to discuss matters of cultural co-operation with our Greek colleagues, the Parthenon Sculptures are owned by the British Museum, which operates independently of government. This is therefore a matter for the museum’s trustees. The UK’s longstanding position on this matter has not changed.”

UPDATE (1 June 2022): When asked on BBC Radio 4's Front Row about the meeting he had requested with the Greek government about the Parthenon Marbles, Lord Parkinson said: "I asked whether Lina Menoni would like to meet ahead of the Unesco meeting. We weren't able to have a conversation beforehand, so we haven't suggested government to government talks about the Parthenon sculptures. They are owned by the British Museum, that is a matter for them. They're governed by the act that set up the British Museum... we have no plans to change the act that makes this the responsibility of the trustees... the government supports the trustees and has no plans to change the law."

Why can’t the British Museum fix its Parthenon Gallery?

Meanwhile, back in London, the British Museum is still struggling to deal with environmental conditions in gallery 18, which houses the Parthenon Marbles.

On 18 May, this door in the British Museum's Parthenon gallery was wide open to increase ventilation “for visitor comfort” © The Art Newspaper

The Art Newspaper took this photograph on 18 May, the same day the museum’s deputy director Jonathan Williams told Unesco delegates in Paris that the British Museum is a competent custodian of the ancient sculptures. It shows an open door in the gallery wall leading to an external museum space. This suggests poor air circulation in the gallery. A museum spokesman confirmed that “on warmer days, we take a range of measures to ensure our visitors’ comfort, and this includes providing additional ventilation”.

The temperature in London on 18 May peaked at a moderate 23°C (73°F), which suggests that the gallery’s climate control system is not functioning as it should. The museum declined to answer questions about this, but the spokesman said that “the humidity and conditions in relation to objects are monitored across the museum. The levels are stable in the Parthenon gallery for the objects. If there ever were a change in levels then changes would be made, but this has not been a problem and objects have never been at risk”.

The poor condition of the museum’s Greek and Assyrian displays has been noted many times. The museum closed its Greek galleries for a full year in December 2020, first because of the pandemic, then because of problems caused by the crumbling infrastructure of the block that houses them. Last July, after heavy rainfall, a roof leaked in gallery 17, an Assyrian gallery adjacent to the Parthenon Marbles display.

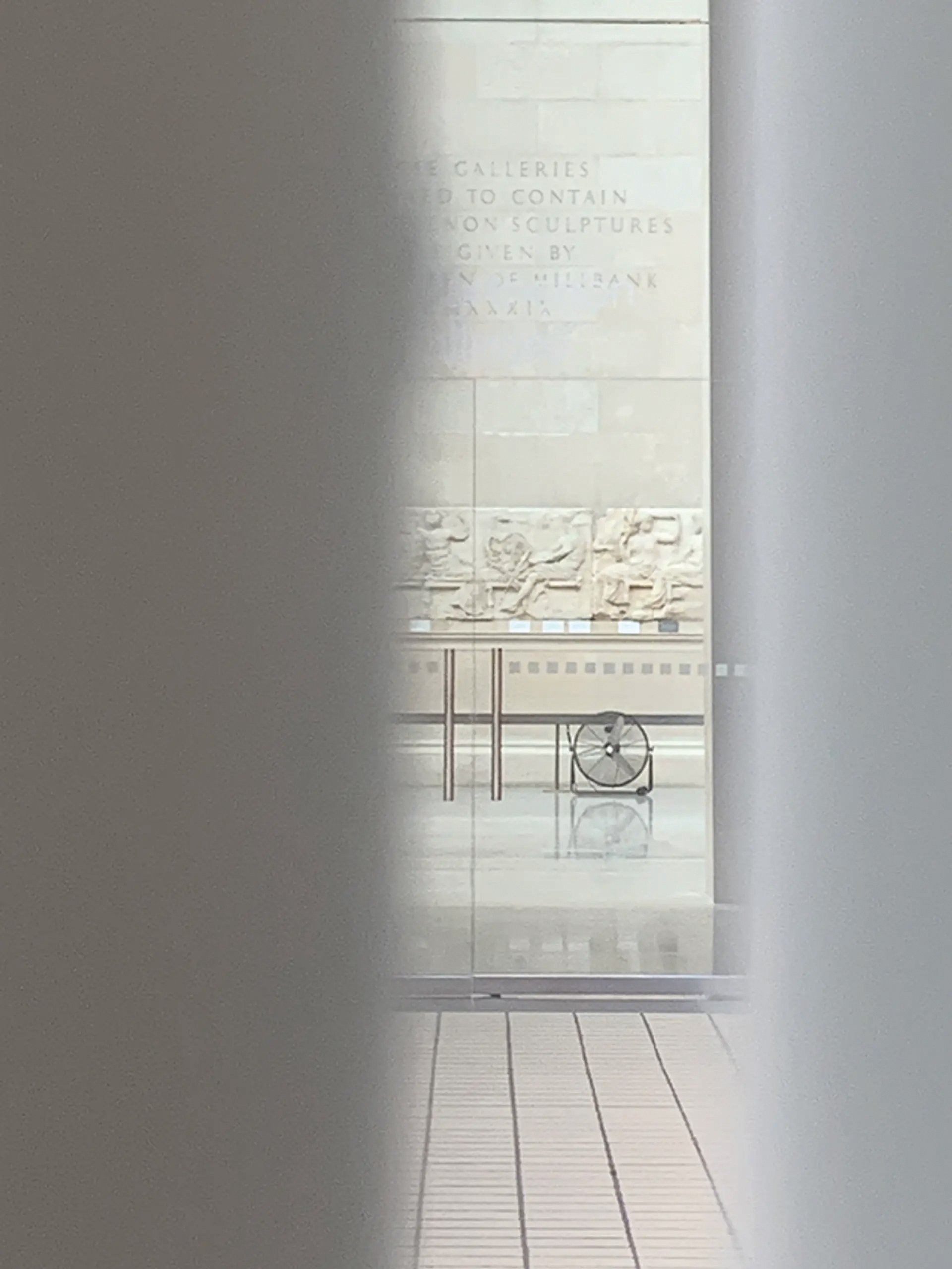

On 10 August 2021, when the Parthenon Marbles were closed to the public, we photographed this fan positioned near the ancient frieze through the gap in the gallery door © The Art Newspaper

In 2018, Greek television broadcast images of water dripping into the Parthenon Marbles gallery, and we have also recorded leaks in the Assyrian and Greek section of the museum multiple times. Last August, when the Parthenon display was closed, we photographed a large fan positioned in front of the ancient frieze in gallery 18, again, presumably to increase air circulation in the gallery. Last October, we photographed an ancient Assyrian frieze in gallery seven that was covered in plastic because of a faulty actuator on the nearby window.

Under its director Hartwig Fischer, the British Museum is planning to overhaul all its galleries and collections, but it will take decades to implement this ambitious project. Until then, it will perform “localised repairs” on its galleries as required.