Julian Sander called The August Sander 10K Collection a “pioneering step” into a “brave new world”. Now, he says, “it’s turned into a shit-show.”

The collection was supposed to be historic. It would mark the first time the archive of a major figure in the history of photography would be made available as NFTs (non-fungible tokens), allowing a historically significant photography collection to be communally owned on the blockchain.

But a long-established cultural foundation in Germany has stuck a serious spoke in the wheels of the project, asserting a huge copyright claim over the August Sander archive. The ensuing court case could set a new precedent—one that may have widespread ramifications for the many photographers grappling with how to enter the emerging NFT market.

Julian Sander, the photographer’s great-grandson © Julian Sander

The plan seemed simple. Julian Sander, August’s great-grandson, would make the legendary German photographer’s entire archive—all 10,700 photographs—available as NFTs on the blockchain marketplace OpenSea. They would, Julian Sander wrote, be “given away as NFTs for free”.

Prospective buyers would only need to pay admin fees, known as minting fees, to own a digital version of one of photography’s most revered artists.

By doing so, the photographer’s great-grandson would “secure the legacy of August Sander on the blockchain”.

The project went online on 10 February. It was driven by the August Sander family estate, which is run by Julian Sander, an art dealer and gallerist based in Cologne who co-represents the August Sander estate, together with the Swiss gallery Hauser & Wirth. The project launched in partnership with the Fellowship Trust, an NFT photography initiative co-founded by the Mexican photographer Alejandro Cartagena, a 2021 Deutsche Börse prize nominee and a champion of NFT photography.

A society documented

The project was launched alongside lucid evocations of August Sander’s historic contribution to photography. Born in 1876 in rural Germany, Sander was the son of a carpenter who discovered photography while working in a mine as a teenager. He was taught to use a camera by his uncle, and initially pursued commercial photography before becoming immersed in the radical artist group the Cologne Progressives.

Sander, who remained in or near Cologne until his death in 1964, created thousands of crucial documents of German society under the Weimar Republic and during the rise of Nazism, a project he termed People of the Twentieth Century.

Sander lost a son, Erich, a member of the Socialist Workers Party, to the Nazi regime in the Second World War. August’s remains are buried next to those of Erich’s in Cologne’s Melaten Cemetery. August Sander’s son, grandson and now great-grandson have each subsequently worked on the photographer’s archive, firmly establishing him as one of the most influential European artists of the past century.

Many photography enthusiasts dream of owning an original Sander print, and trades of the 10K Collection were initially brisk. More than 400 Ether (ETH, currently equivalent to around $1.1m), was traded in a few weeks. Photographers of the calibre of Gregory Halpern, a Magnum nominee, told his many followers he had bought a Sander NFT from the 10k Collection. “I keep hearing photography will never be the same,” Halpern said. “Now it really won’t be.”

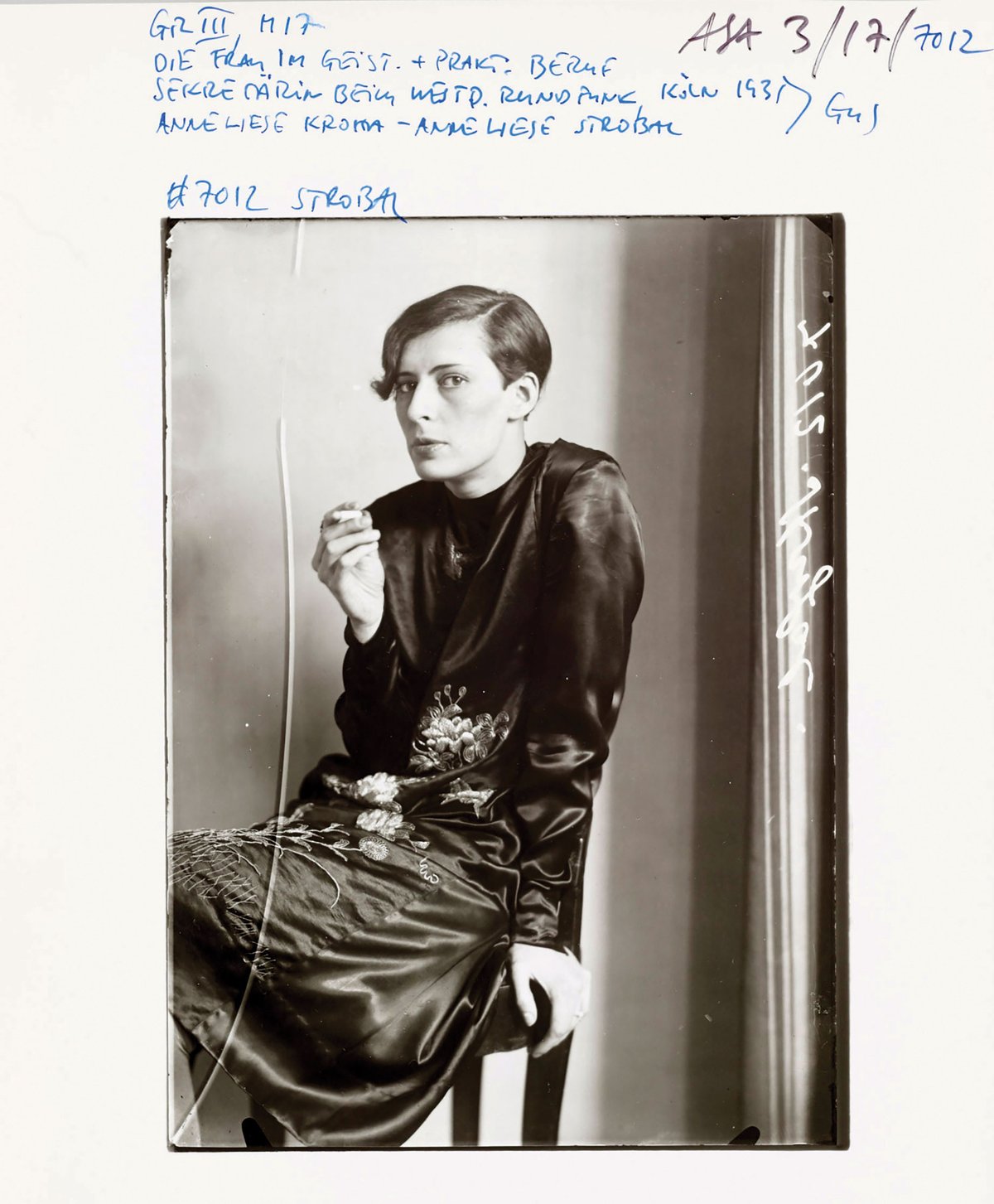

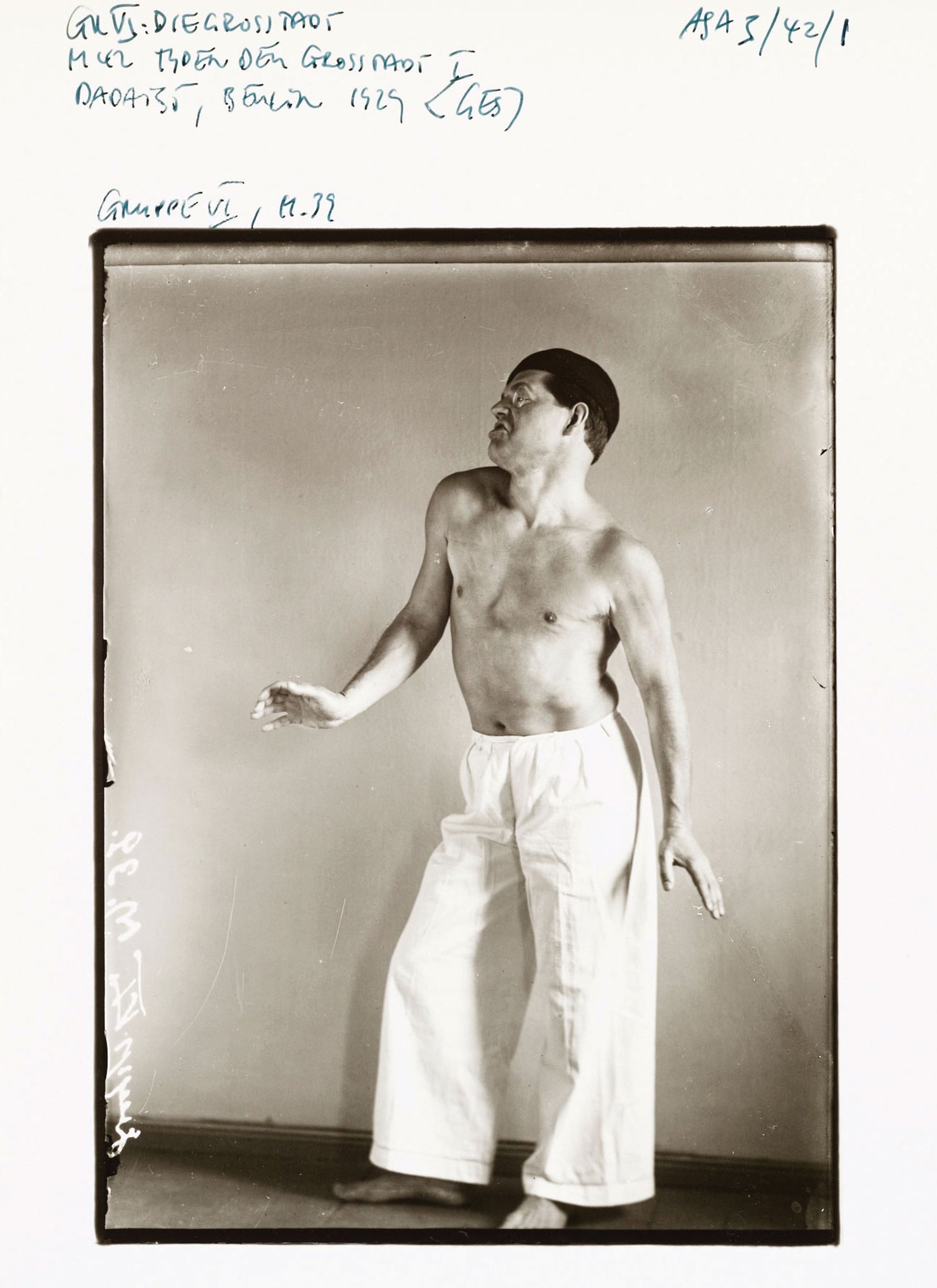

August Sander’s Raoul Hausmann as Dancer (1929) August Sander Archive

Many photographers proudly displayed their new Sander purchase on their social media feeds alongside the NFT greeting “GM” (“good morning”, a reference to the dawn of a new age).

And then, without warning, the collection disappeared. The archive, it emerged, had been delisted from OpenSea. The reason: Julian Sander does not own the copyright to August Sander’s body of work, it is claimed. The 10k Collection, if the claim is true, is thus a violation of copyright law, and all the Sander NFTs trades thus far may be in breach.

The copyright claim came from SK Stiftung Kultur, a Cologne-based nonprofit cultural foundation. In 1992, Julian’s father and August’s grandson Gerd Sander, also a Cologne gallerist, sold August Sander’s archive to SK Stiftung Kultur, with whom he had worked closely throughout his career. SK Stiftung Kultur holds the copyright to the archive until 20 April 2034.

From 1992 onwards, therefore, the distribution and preservation of 10,700 original negatives and approximately 3,500 vintage prints was the responsibility of the foundation, and not Sander’s family.

After the 10k Collection went live, SK Stiftung Kultur approached OpenSea with a takedown notice. OpenSea complied on 7 March by suspending the sale.

SK Stiftung Kultur did not respond to a request for comment. But a terse statement on its website states: “The foundation exclusively holds… unlimited in terms of location, content and time” all of Sander’s work, and so “is the only legitimate representation of the estate of August Sander”.

On 18 March, 11 days after the project was delisted on OpenSea, the Fellowship Trust and Julian Sander responded with a statement. In it, they acknowledged “a third party… claims to have certain rights to August Sander’s photographs”.

“But I believe the complaint is not valid,” Julian Sander says.

Speaking to The Art Newspaper, Sander expresses anger at the disruption the takedown notice has caused, describing it as: “A ridiculous waste of time and money for everybody.” He adds: “The people who are perpetuating this fight should be ashamed of themselves.”

Sander actively positioned the 10K Collection as a unique innovation of Sander’s archive. When introducing the project, he wrote: “We are building a platform to help this collection become a case study of how photographic legacies can be not just preserved but amplified by community, decentralisation and the blockchain.”

Resale detail

What was not clearly mentioned was the royalties scheme. Initially, buying an August Sander NFT was close to free; a trader would only have to pay the initial minting fees to own one. But, for all resale transactions thereon, a 10% royalty cut would be taken via a smart contract, with Julian Sander receiving 7.5% of all resales and Cartagena’s Fellowship Trust taking the remaining 2.5%.

The veiled commercialism of the project has been debated hotly, with prominent photographers questioning its motivations.

No, I’m not trying to get rich… I am rich. I don’t need thisJulian Sander, gallerist

Sander tells The Art Newspaper: “People are jumping on the point. They’re all saying: ‘Oh my god, he’s just trying to get rich.’ No, I’m not trying to get rich… I am rich. I don’t need this.”

Nevertheless, Sander argues that the commercialism of the project ensures its legitimacy in copyright law. As a non-profit organisation, the SK Foundation is not responsible for the sale of works on the global art market, allowing Sander, from his point of view, to publish the images in commercial settings, including, in this instance, an NFT marketplace.

This means Sander was able to create the 10K Collection on OpenSea without involving SK Stiftung Kultur because of “fair use”, a technical term used in copy-right law under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

“OpenSea is a marketplace,” he says. “That’s essential to this disagreement.” To try and sell pictures in this new market, Sander points out, is just as valid as trying to sell pictures in a physical art fair, or in a private gallery on Cologne’s high street. Each is a marketplace as valid as the other. As a gallerist, I work inside of the realm of fair use,” he says. “As a businessman who sells pictures, I’m legally allowed to sell pictures, and to make money doing it, via fair use. There’s a clear framework there.”

He adds: “One of the things SK and their attorneys misunderstand is they look at OpenSea as if it were Google Images,” he says. “OpenSea is a marketplace; everything is for sale. That’s why I could do this project. Because putting something on OpenSea means it’s for sale. And if it’s sellable, I’m allowed to show it. That’s why I didn’t even consider asking SK for approval.”

Sander also says he was planning to split some of the royalties accrued from resales with SK Stiftung Kultur.

“From that 7.5%, I always intended to give a part of it to SK,” he says.

The rest of the proceeds would be put towards “paying myself back for the hundreds of thousands of Euros I’ve put into building all of the data structures,” he says. “None of this exists for free. I don’t buy the argument that culture should be free.”

SK Stiftung Kultur and Sander are now locked in a legal battle, the outcome of which will not just determine the future of this project, but the way copyright law, as it is understood in the present day, translates to the Wild West of blockchain technology.