The breaking of the Enigma Code at Bletchley Park has become a very British story of almost cosy espionage. We may have been beastly to Alan Turing, the narrative goes, but he and fellow boffins and Wrens (The Women's Royal Naval Service)—with hair pinned up in victory rolls—still invented electronic computing and saved the world from the Nazis, fuelled only by endless tea and limited tobacco rations.

The story has taken a new, and sometimes disturbing, turn with the opening of the 650 sq. m Intelligence Factory this week—the museum’s largest ever gallery.

The Bletchley Park Mansion was the headquarters for British codebreakers during the Second World War Photo: DeFacto

The forerunner of the UK’s spying signals organisation GCHQ (Government Communications Headquarters), Bletchley Park was set up in a country house in Buckinghamshire. Its codebreaking operations expanded across a series of utilitarian huts across the estate until, at its wartime peak, almost 9,000 people worked there tracking U-boats and deceiving the Germans ahead of D-Day. Coded Nazi messages were intercepted and translated using the innovative Bombe machine and Colossus computer. In 2014, the complex opened as a visitor attraction under a charitable trust.

The Bletchley Park library is one of the more old-fashioned room sets Photo © David Dixon (cc-by-sa/2.0)

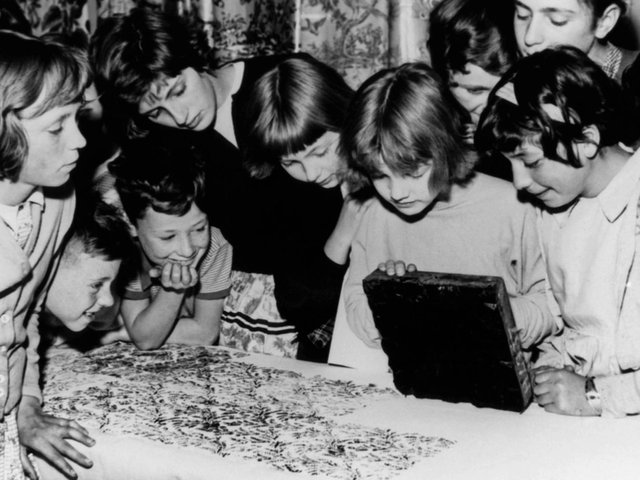

The main house has old-fashioned room sets that continue with a cosiness that conceals dead seriousness. Traditional exhibition design sees smoking pipes glued to ashtrays as if a colonel has just stepped away. Old-fashioned typewriters clatter and black rotary telephones ring in empty salons. Other huts and blocks explain the workings of Enigma machines and house copies of Enigma’s ingenious computing nemesis. It’s all very analogue and fuddy-duddy.

By contrast, the Intelligence Factory by the exhibition designers Ralph Appelbaum Associates seeks to bring the storytelling up to date. It reactivates the previously unused Block A, whose wings have been divided into two permanent suites of rooms to tell the story from 1942 to 1945 and one temporary gallery.

Visitors are greeted by massive digital screens displaying battle footage before entering a sequence of brick rooms restored in heritage colours. A small number of artefacts are on show alongside digital versions of giant plotting maps on the walls and tables. These allow a degree of interaction in an attempt to immerse visitors in the experience of stalking enemy ships and planes, making connections on peg boards or sifting through card indexes to compile intel on what your foe is up to.

The Naval Plotting Room, part of the Intelligence Factory, Bletchley Park Courtesy of Bletchley Park Trust; photo: Andrew Lee

There is also a focus on the personal stories of those who worked in shifts around the clock, turning a mountain of messages into actionable intelligence. Practical necessities—such as feeding everybody—attempt to humanise this history (here, the illustrations of school dinner-like portions are a little lame).

[GCHQ’s] current work is presented as an unproblematic continuation of Bletchley Park's anti-Fascist heroism rather than that of an organisation found guilty in the European Court of Human Rights of eavesdropping on millions of people’s private data.

But cosy turns creepy with the use of "time portal" installations throughout the rooms that celebrate GCHQ’s intelligence work today. With a former director of GCHQ on the trust’s board this is hardly surprising. The spy agency’s current work is, however, presented as an unproblematic continuation of Bletchley Park's anti-Fascist heroism rather than that of an organisation found guilty in the European Court of Human Rights of eavesdropping on millions of people’s private data.

The name of the lead sponsor BAE Systems also features prominently throughout, although the museum has declined to disclose the project budget. As Britain’s leading weapons manufacturer, BAE Systems has sold £17.6bn worth of aircraft, weapons and services to the Saudi military since 2015, when Riyadh began bombing Yemen. In Bletchley's first temporary exhibition, The Art of Data: Making Sense of the World designed by Easy Tiger, a BAE Systems Striker fighter pilot helmet is on display showing its 3D rendering of a sortie over Afghanistan. Again, not an uncontroversial campaign.

We are not still fighting the Nazis here. Bletchley Park curatorial decisions are not all cosy. Edward Snowden might have a different perspective, as would Extinction Rebellion who the government have declared a cyber-threat. This factory elides an honourable history with a contested present and insults our intelligence in the telling.