A lot of us, at some point in our lives, want to make a difference in the world. Nan Goldin actually has. Her searing, tender, diaristic and memorialising slide show, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, was an innovation in the late 1970s, when she first started showing it. At the time, many people who should have known better did not regard her photographs—expertly composed, raw, richly saturated in colour and absolutely fearless portraits—as art. By the mid-1980s, she was a force. More recently she has been widely and justifiably recognised for her hugely effective campaign to remove dirty money from the killer opioids produced by members of the Sackler family out of the many museums bearing its supposedly philanthropic name. Yet it took until now for someone—Cecilia Alemani, that is—to bring her work to a Venice Biennale.

From left: Nan Goldin; and the curator Milovan Faranoto with Linda at the dinner held in Nan's honour Photos: Linda Yablonsky

“It’s my first biennale and it has the only happy work I ever made!” she joked on Tuesday night, at the dinner Marian Goodman Gallery held in her honour in the Fortuny Factory Gardens on the Giudecca. The work is Sirens (2019-21), a seamless film collage (accompanied by an otherworldly, whistling soundtrack by the composer Mica Levi) that ideally suits the “enchantment” part of Alemani’s thesis for her exhibition. An earlier version of the work appeared in Goldin's debut show with the gallery a year ago. “I changed it,” she said. It was poignant then. Now it’s joyful.

Marian Goodman, 94, was wary of travelling in these Covid-19 times and was sorely missed. But artists Julie Mehretu and Nairy Baghramian stepped into the breach to give an impromptu toast welcoming Goldin to the fold. Clearly moved, Goldin told them that it had been a longtime dream to join the gallery—the best in the world, she said—“because of the artists, and because of Marian’s morality, not just her aesthetics”. The Artforum editor David Velasco—the commissioner of the self-portraits and essay in which Goldin revealed the downward spiral of her addiction to, and subsequent recovery from, prescribed opiates—added his own words of esteem. "That's how Pain (her activist group, Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) began," Goldin acknowledged. "So, thank you!"

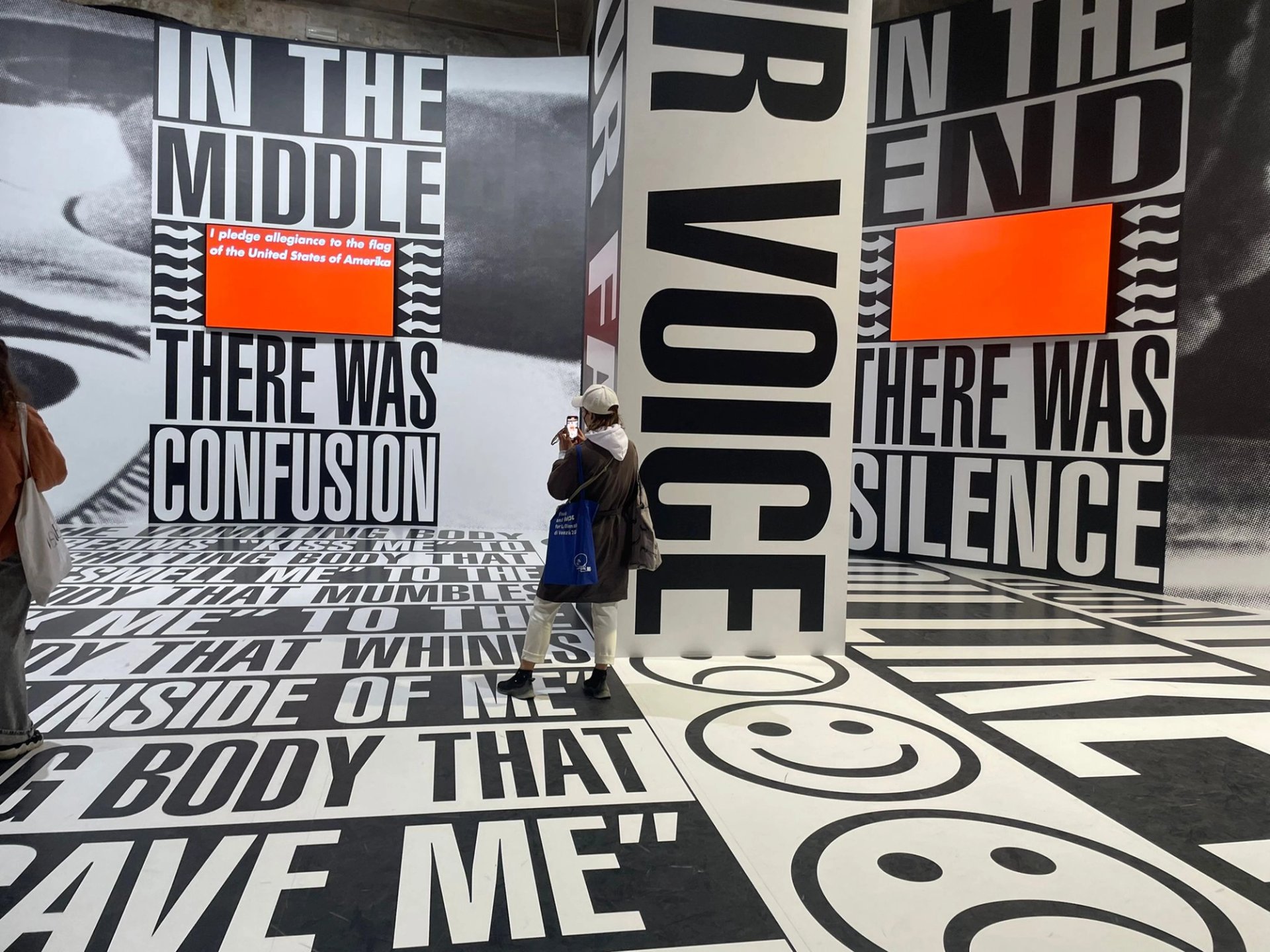

Barbara Kruger's Untitled (Beginning/Middle/End, 2022) installation at the Venice Biennale's main exhibition Milk of Dreams Photo: Aimee Dawson

Personally, it was very satisfying to see Goldin’s work in the Biennale placed in close proximity to exhilarating installations by Louise Lawler, Barbara Kruger and Amy Sillman. Incredibly, this is the first Venice Biennale appearance for each of them, too. And the big stage is more than ready to receive them. How can you stay relevant in a world that changes focus on a dime? “You just need to pay attention, I guess,” Lawler reflected.

I keep thinking about Alemani’s exhibition, The Milk of Dreams, particularly the part in the Giardini. Did any previous Biennale there feature plush carpeting and pigmented walls? Astonishing on its own, the design enhances every work it graces. (Some credit goes to FormaFantasma, the Italian design studio that worked with Alemani, with thanks to the David Teiger Foundation for extra funding.) “The installation is impeccable,” said a dazzled Jack Shear, whose collection of works on paper recently had an equally impeccable run at the Drawing Center in New York.

The artists were just as thrilled. “I’m so happy with this room!” exclaimed Charline von Heyl, whose Pop-ish abstractions came out of a musical collaboration with the Prima Vera project involving no less than 81 cello solos by as many musicians. (The playlist is on the wall and online.)

“I’m thrilled,” echoed her BFF, Jacqueline Humphries, whose impastoed and monumental abstractions resonate with the show’s technological undercurrents, another theme that brings one surprise after another. Witness a 1978 digital animation by the pioneering US artist Lillian Schwartz (born 1927) alongside the cosmic eyeballs painted by the modest Swedish artist Ulla Wiggen (born 1942).

Indeed, the breadth of knowledge and self-assured, grandstanding nature of this exhibition—from Rosemarie Trockel’s gorgeous array of textile paintings to Paula Rego’s navy blue room of paintings and puppets—whipsaws the eye and the brain. On the whole, it's an emotional and uplifting show.

From left: the Ukrainian pavilion architects Iryna Miroshynykova and Oleksiy Petrov with the curator Maria Lanko Photo: Linda Yablonksy

I was trying to still my heart when I happened across the curator Maria Lanko, curator of the Ukrainian pavilion. She was taking a break outside with the architects who designed Fountain of Exhaustion: Acqua Alta (1995–2022), the installation by the artist Pavlo Makov. His tranquil “fountain”, a pyramid of tin cones based on the Tin Man in the Wizard of Oz, brings a certain peacefulness to chaos. It also comments on the water that stopped flowing when the invading Russians cut it off, as well as the unquenchable thirst for freedom that continues to fuel the people of his decimated country. Like the clanking Tin Man greasing his joints, it's healing. Of course, he needed help too.

What has it been like for this group in Venice while the bombs fall at home? "Every day and every night we read the headlines,” said Lanko. “And we just want to cry.” And what of the representatives of India, China or the UAE, who have not joined the unified Western stand against Russia? “Silence,” she replied. “Just silence.”