In August of last year, the independent dealers Jeanne Greenberg Rohaytn and Amalia Dayan announced their operations’ consolidation with Levy Gorvy gallery co-founders Dominique Lévy and Brett Gorvy to form a single entity: LGDR. At the time, the merger struck many as a defensive move against artist- and territory-gobbling mega-galleries but appeared more likely to benefit the dealers than the artists they represented. Yet LGDR, the dealers said, would be “a partnership devoted to artists.” It would not participate in American art fairs, nor would it continue the exclusive representation of every artist and estate left on the combined rosters so much as look after their interests in the global market. Whatever that meant.

During a hurried, mid-pandemic/post-George Floyd rejiggering of power structures within art world, the dealers’ circle-the-wagons move made a certain survivalist sense. Nonetheless, it was difficult to imagine even collegial competitors with distinctly different programs working together without generating friction between them or their equally competitive clients.

Installation view of Stage Fright at LGDR. Courtesy of LGDR

On Monday, 4 April, the fog began to lift with the opening of three exhibitions under the new LGDR banner. What emerged was a split personality with mutually agreeable portents. For now, at least, the dissolved galleries will cohabit under two roofs not one, as The New York Times reported initially. Over the next year, LGDR will keep presenting exhibitions in the former Lévy Gorvy space as well as in the building at 89th Street, a half-mile to the north, where remodelling will give all four partners office space. To celebrate the rebranding, they invited the artist Rachel Harrison, whom they don’t represent, to stage a kind of pop-up show of 20th-century sculpture.

Frankly, it would take dealers with the resources of these two secondary-market veterans to fulfill Harrison’s request for primo works by Marcel Duchamp, Alina Szapocznikow, Marisol Escobar, Louise Bourgeois. Alberto Giacometti and Constantin Brancusi. But it is Harrison’s interventionist presentation that makes what could have been a routine show into the joyful surprise that is Stage Fright.

Harrison didn’t just select the works on view—“all body parts,” as she pointed out. (Only one piece, presumably the Bourgeois, has a price tag). She mounted all but Marisol’s The Blacks (from 1961-62, after the Jean Genet play) on ingenious mounts of her own design that enhanced the whole experience for sculpture and viewer alike. Brancusi’s bronze infant’s head (Le premier cri, 1917), gender unknown, sat on a stained plywood plank, skirted, as it were, with a colorful, Mike Kelley-ish (and gender-nonspecific), knitted baby blanket found on eBay. Duchamp’s 1964 repro of Fresh Widow stood tall on a Stanley Wet/Dry vacuum cleaner box encased, a la Jeff Koons, in a clear Plexiglas box. A small Giacometti bronze, Buste de Deigo au col roule (1951), was on another clear Lucite box, but one that put the sculpture below knee level. That left the 1968 Szapocznikow plaster, Ventro (Belly) and the Labyrinthine Tower (1962) by Bourgeois to display themselves on painted wooden plinths, foregrounding a wall-spanning vinyl print of a bright red, long-stemmed rose of a sponge stuck in a stone that Harrison made from a work by Yves Klein, whose estate has been managed by Lévy Gorvy.

Only another artist could link the contemporary to the modern with such glorious panache. The independent curator Alison Gingeras, who has worked frequently with Dayan, suggested her for the job. “They wanted a sculpture show that would be something different,” Harrison told me, as she introduced the woman from Minnesota who bought the Marisol with her late husband when it was new and still owns it. Going her own way, as ever, Harrison departed for dinner with her primary dealer, Carol Greene, and gallery-mate Jacqueline Humphries, while collectors Charles and Nathalie de Gunzburg drove the 16 blocks north to the glam scene taking place in the five-story, Gilded Age townhouse opposite the Guggenheim Museum that is now the LGDR flagship.

Greenberg Rohaytn bought the 17,500 sq-ft building (formerly the National Academy of Design) in 2019 for a reported $22.3m. After a pragmatic renovation by her usual architect, Rafael Viñoly, exhibitions from her three existing Salon 94 spaces moved into this decidedly more splendiferous setting. On opening night, all four dealers mingled among the unusually multigenerational and mixed-race crowd attending the inaugural show, which featured exhibitions by two very different painters from London, neither of whom is on listed on the combined gallery’s web site.

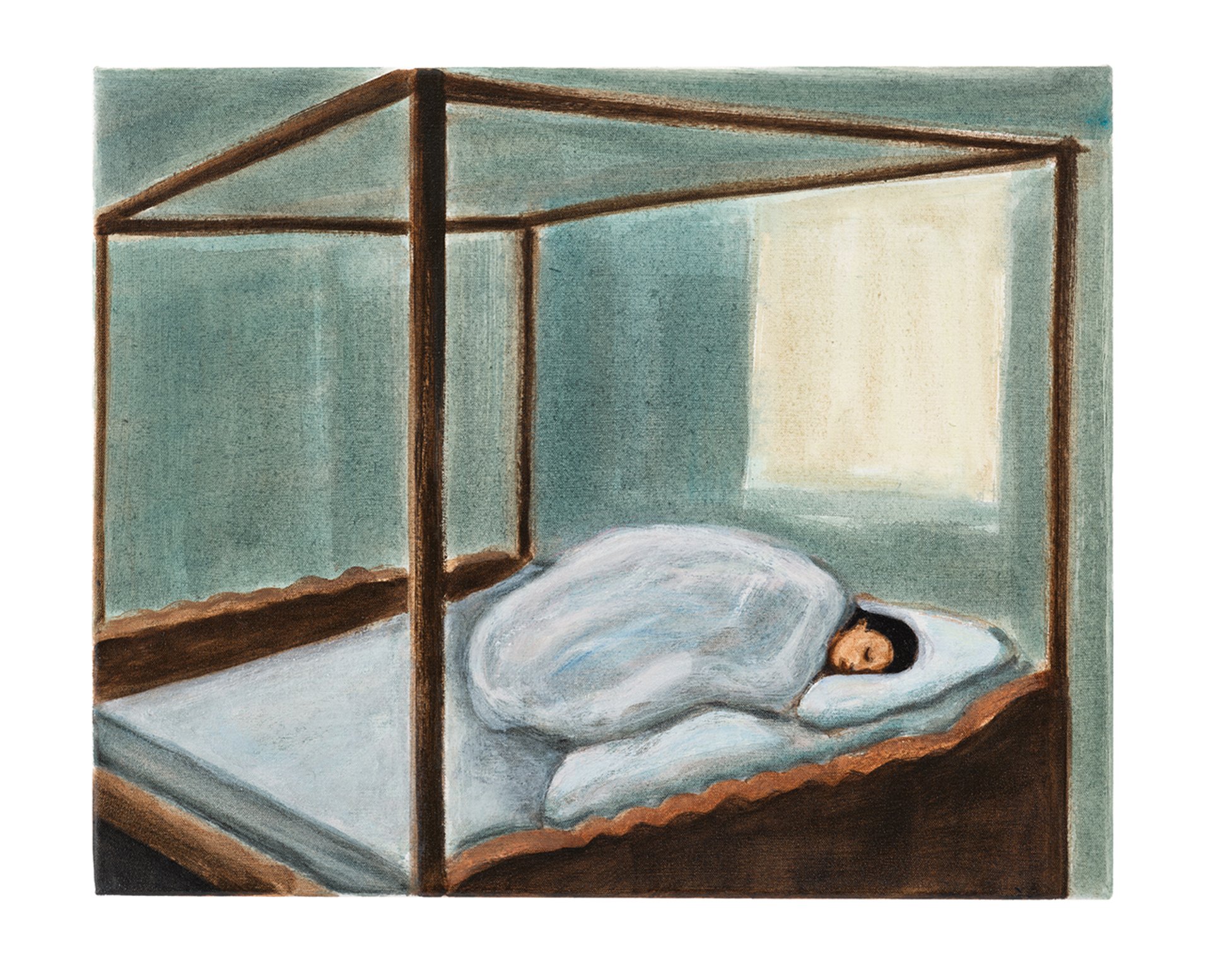

Matthew Krishanu's Four Poster Bed (2022). Courtesy LGDR

Young Matthew Krishanu is the British-born son of a white English father and Indian mother, missionaries who moved the family to Dhaka, Bangladesh, the site of Krishanu’s adolescence. His modest, narrative landscape paintings and interiors, based on snapshots, depict that upbringing, but the standout is a portrait of his wife, who died last year. Accompanied by Amrita Jhaveri, his primary dealer in Mumbai, Krishanu seemed dazzled by his surroundings, which included the actor Matt Dillon. “This is my first time in New York!” he said, happily, yet to discover that the rest of the city is not quite as posh as the Upper East Side, and that some of those present did not live in homes with ceilings of the celestial height natural to LGDR.

The South African-born Lisa Brice, who moves between studios in London and Trinidad, where her neighbours are Peter Doig and Chris Ofili, caught attention from major American collectors last November (finally), when a painting from 2017 zoomed to a record price of $3.1m at Sotheby’s. At LGDR, she made the most of the spacious rooms given the pandemic-delayed arrival of Last Chance Salon, the punning title for a soulful and seductive show of louche female nudes, including those of Helen Frankenthaler, Lee Krasner and herself, on canvas, folding screens and tracing paper. Colours of choice appeared to be absinthe green, flesh, and blue.

"Lisa," said Greenberg Rohaytn in her toast during the vegetarian dinner for 60 that followed, in a warm, wood-panelled room, "you have rewritten history with your brush." She certainly owned it at this heartwarming, family affair. Brice’s South African BFFs—Justine Koons, Sue Williamson (whose studio assistant Brice once was), Williamson’s daughter Amanda, and Clare van Zye (a producer of television commercials) all came in from a driving rain to join the gallerists’ spouses and significant others (Lévy also brought her mother), gallery artist Derrick Adams, collectors Wendy Fisher, Glenn Furhrman and Ann Tenenbaum, Dia director Jessica Morgan (who had recommended the chef, Olivier Cheng), and Brice’s English dealer, Stephen Friedman, still getting used to his role as new father.

“As a dealer, it’s all about trust,” Levy told her guests, echoing what Gorvy had told me earlier. “This is a collaboration between four like-minded individuals and friends,” he said, who have come together to “add value” to their artists’ projects by positioning themselves as advisors to the artists’ careers. Clearly, they can come from anywhere, even a downpour, and make quite a splash here.