Boris Iofan (1891-1976), the Odesa-born subject of this new biography, is known for two buildings, both of which might be, arguably, better described as plinths for giant sculptures. It doesn’t seem much of a legacy.

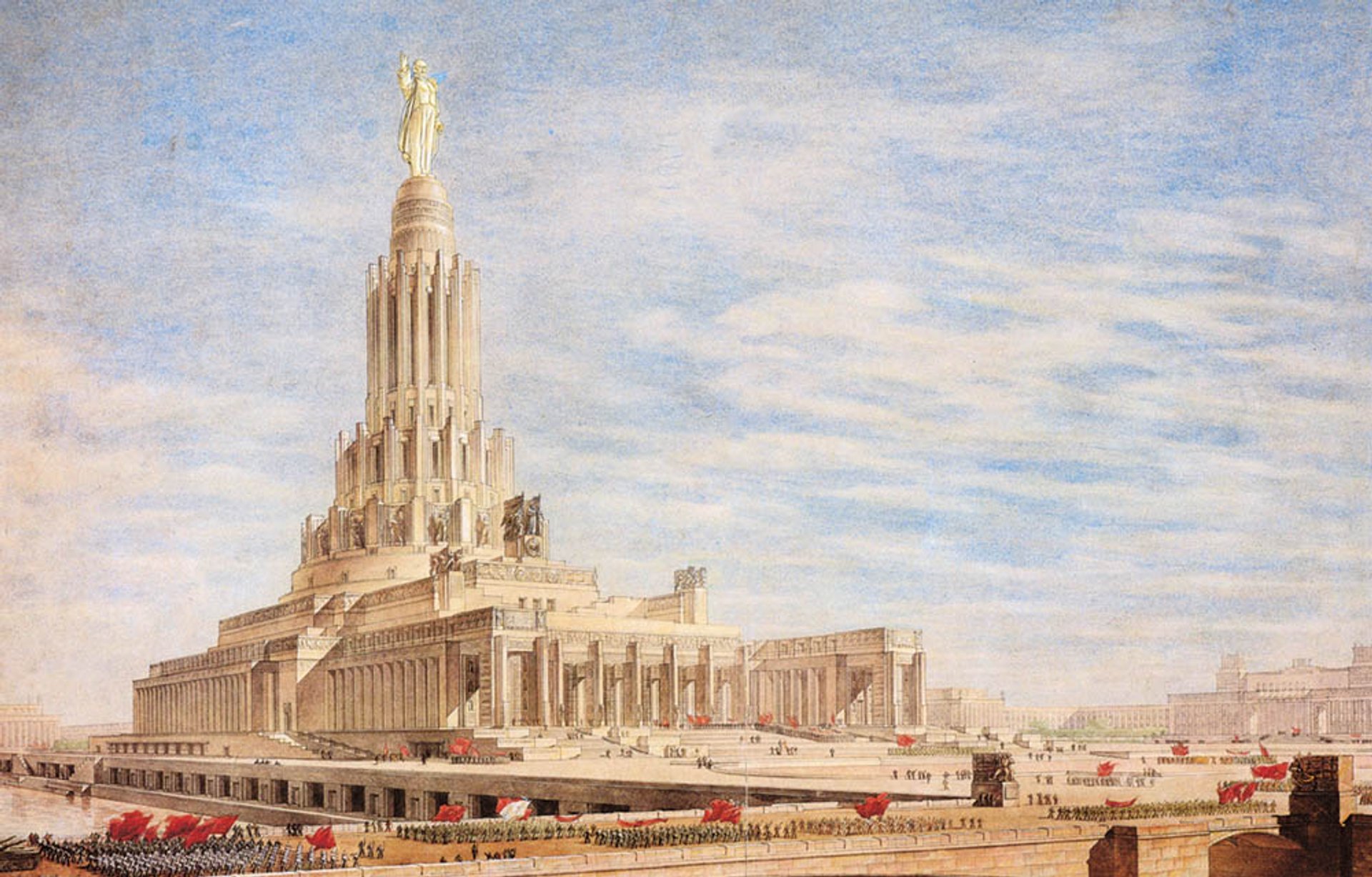

The first was the Palace of the Soviets. One of the most famous of all unbuilt buildings, this was the attenuated wedding cake capped by the familiar Lenin-hailing-a-taxi sculptural figure that became such a widespread motif across windswept Eastern Bloc landscapes. Intended to be the tallest building in the world, it was a riposte to Manhattan: a Soviet skyscraper style for Stalin. This was the building for which the late-Romanov-era Cathedral of Christ the Saviour (which had stood for barely 50 years) was demolished. Its huge, waterlogged site by the Moskva River later became a lido and then a cheesy replica of the original cathedral was built. As if nothing had ever happened.

Dictatorship face-off

The other building was the dynamic Soviet pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exposition. A stepped Art Deco platform filled with tractors and Constructivist graphics, the abstract geometries of radical Russian art translated into propaganda about the awesomeness of everyday life in the Soviet Union. It coincided neatly with the Great Purge of Stalin’s political opponents back home, with 700,000 deaths a conservative estimate. The building was topped by a pair of Stakhanovite workers: he holding a hammer, she a sickle. Its success was in facing off Albert Speer’s grim, columnated structure for the Nazis opposite, this one crowned by an ominous eagle. That image of the two dictatorships toe to toe with a “did you spill my pint?” intensity is how they will be remembered.

It might be better, though, to look at two of the buildings Iofan designed that did survive. The first became known as the “House on the Embankment” (1928-31), a solid, Constructivist pile that housed the Communist party elite—including Iofan himself. It was much more a part of the radical direction of early Soviet architecture, an urbane modernism of luxury. The other was Moscow’s Baumanskaya Metro Station (1944), a restrained, stripped classical building, an enduring people’s palace. Both are excellent, if very different buildings. Iofan managed, somehow, to survive the most brutal of regimes, falling in and out of favour, remaining close to a notoriously fickle and—given Iofan was Jewish—increasingly antisemitic Stalin.

American influence

Iofan had spent a decade studying and working in Italy, imbibing classical architecture—he graduated from Rome’s Regio Istituto Superiore di Belle Arti in 1916—before finding himself back in the turmoil of the Soviet Union and attempting to carve out a distinctive image for its cities. On a visit to the United States in 1934 he was deeply impressed by Manhattan’s skyscrapers and, particularly, the Rockefeller Center, touches of which (as observed) appear in his later works. The gorgeous pencil sketches reproduced here in the book show a real empathy for the American development of Art Deco as a defining skyscraper style and a contemporary classicism. But he was equally in awe of the ghastly kitsch of Rome’s Vittorio Emanuele II Monument. Iofan’s oeuvre was defined precisely by that split between classical puddings, garish commercial Deco and fascist-tinged De Chirico classicism. And it is probably just as well his masterwork never got built.

One of Boris Iofan’s many designs for the unbuilt Palace of the Soviets, topped by a giant statue of Lenin and planned for the centre of Moscow © Album/Alamy Stock Photo

With this book published not long after Maria Kostyuk’s richly illustrated and scholarly Boris Iofan: Architect Behind the Palace of the Soviets (RIBA/DOM 2018), Deyan Sudjic, architecture critic and former director of London’s Design Museum, is surprisingly sympathetic. He has written a breezy and readable text accessible to a broader, non-specialist audience on a complex period, and he deals with the cascade of names and denunciations, political shifts and relationships with agility and ease. The drawings included are both seductive and ridiculous, an odd cocktail of ambition and self-parody yet still occasionally sublime. If there is a criticism, it might be that Iofan himself seems a little absent. His character remains as sketchy as his vague but elegant concept drawings.

Iofan’s megalomaniac, kitsch classicism is alive and well

This was an era when architectural criticism could contain real jeopardy—to be denounced at a congress or a committee could see you disappear. Architecture mattered. Reading Stalin’s Architect as Russian artillery is bombarding Ukrainian cities still defined by their Socialist Realist centres was uneasy. Looking at the phallocentric towers ejaculating their ludicrous Lenins you can’t help thinking of Putin’s ridiculously long table, his tacky, marbled interiors or Alexei Navalny’s video about Putin’s alleged, grotesque neoclassical palace. Iofan might have died largely unloved, but his megalomaniac, kitsch classicism is, arguably, alive and well.

• Deyan Sudjic, Stalin’s Architect: Power and Survival in Moscow, Thames & Hudson, 320pp, 60 colour & b/w illustrations, £30 (hb), published 28 April

• Edwin Heathcote is the architecture and design critic for The Financial Times and deputy chair of Blood Mountain, a cross-disciplinary research and curatorial platform based in Budapest with a remit in Central Europe’s cultural past, present and future