Conjuring up come-hither connotations of strip-joint signage and blokey songs by Elvis, Jay Z and Mötley Crüe, girls girls girls is not the most obvious title for a serious exhibition of female artists. "I like the idea of it being tongue-in-cheek and slightly provocative," says fashion designer Simone Rocha of her choice of name for the multigenerational, 19 artist show that she has just curated for Lismore Castle Arts, the contemporary art programme at Lismore Castle, the Irish home of the Dukes of Devonshire.

Fashion designer and curator Simone Rocha. Photo: Gabby Laurent

Dublin-born Rocha is the multiple award-winning creator of edgy womenswear that plays with traditional notions of femininity: think exaggerated ruching and ruffles, flowing ribbons and bows, dangling blood-ruby earrings and knee socks adorned with encrustations of pearls. Her puffy, flouncy, lacey and sometimes leathery dresses are flamboyant, theatrical and exquisitely made and have won her a high profile fanbase which includes Billie Eilish, Chloë Sevigny, Renée Zellweger and Rihanna. But at the same time, Rocha’s togs seriously mess with material and stylistic conventions, and this spirit of darkly subversive mischief resonates in much of the work she’s selected for the show.

Louise Bourgeois's Janus in Leather Jacket (1968).

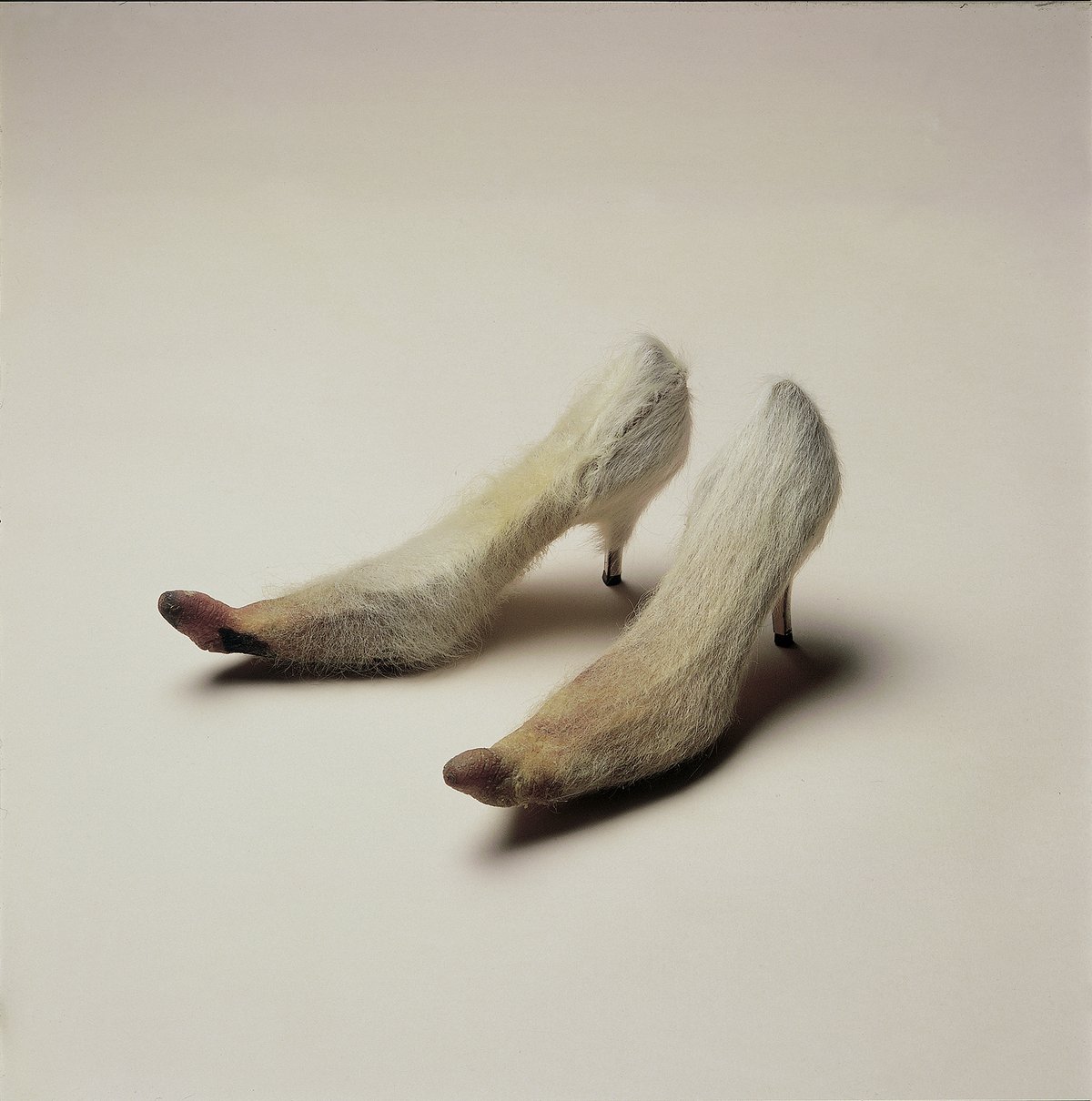

After all, there’s nothing demure nor obedient about Louise Bourgeois’s dangling double-phallic bronze Janus in Leather Jacket (1968); Dorothy Cross’s nipple-toed cowskin stilettos or fashion photographer Harley Weir’s untitled photograph made earlier this year of an adult woman dreamily suckling on the breast of another. In Genieve Figgis’s recent painting Upstairs Downstairs (2021), figures in maid and butler’s uniforms are lined up as if for a formal photograph but, in a scenario where Downton Abbey merges with James Ensor, this orderly domestic arrangement has been horribly distorted by way in which all their faces seem to have melted into grotesquely cadaverous masks. Figgis’s zombie workforce takes on a particular resonance within the context of Lismore Castle, a place of fairytale beauty underpinned by centuries of behind-the-scenes domestic toil.

Installation view of girls girls girls at Lismore Castle Arts. Photo: Jed Niezgoda

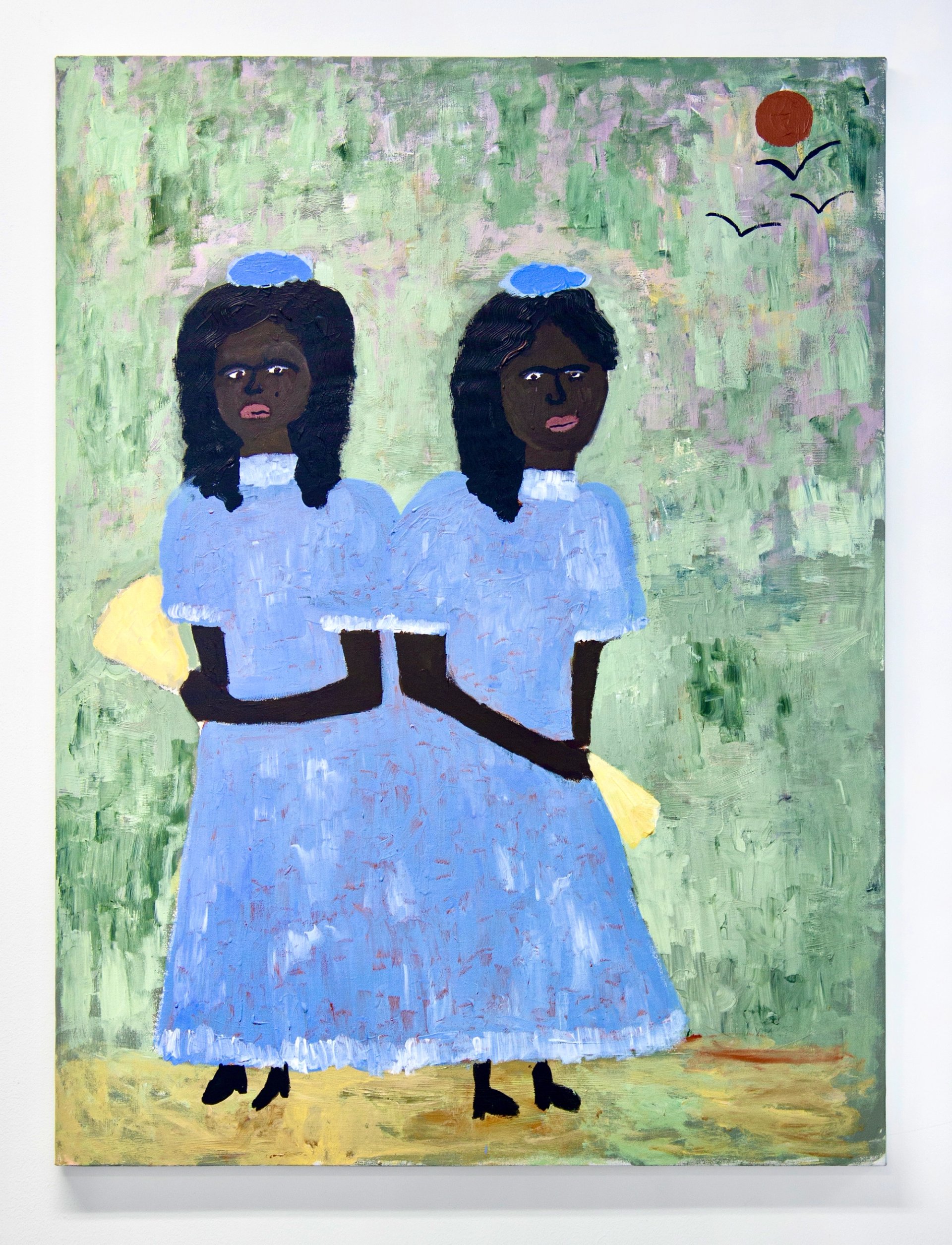

Perhaps not surprisingly given the day job of the curator, the various ways in which clothing can signal, shape and also distort identity is a conspicuous theme. Many of the works on show also chime with Rocha’s emotionally-charged use of sometimes incongruous materials. Along with Cross’s hairy mammary footwear, Bourgeois’s shiny, sheathed double phallus and Figgis’s impasto uniforms, other suggestive garments include the voluminous and somewhat Rocha-esque white dresses worn by the little girls in young Irish artist Sian Costello’s lushly executed series of Wishful Self Portrait paintings; and the sprigged floral shirt that Iris Häussler has uncannily suspended in a block of translucent wax like an embalmed religious relic. The innocent cuteness of the powder blue frocks and matching hats worn by the pair of girls painted by Cassi Namoda only renders all the more horrific the fact that they were conjoined twins who had been sold as slaves for display in a circus.

Cassi Namoda's Anxiety … Untitled, Conjoined Twins (2020). Photograph: Courtesy the artist

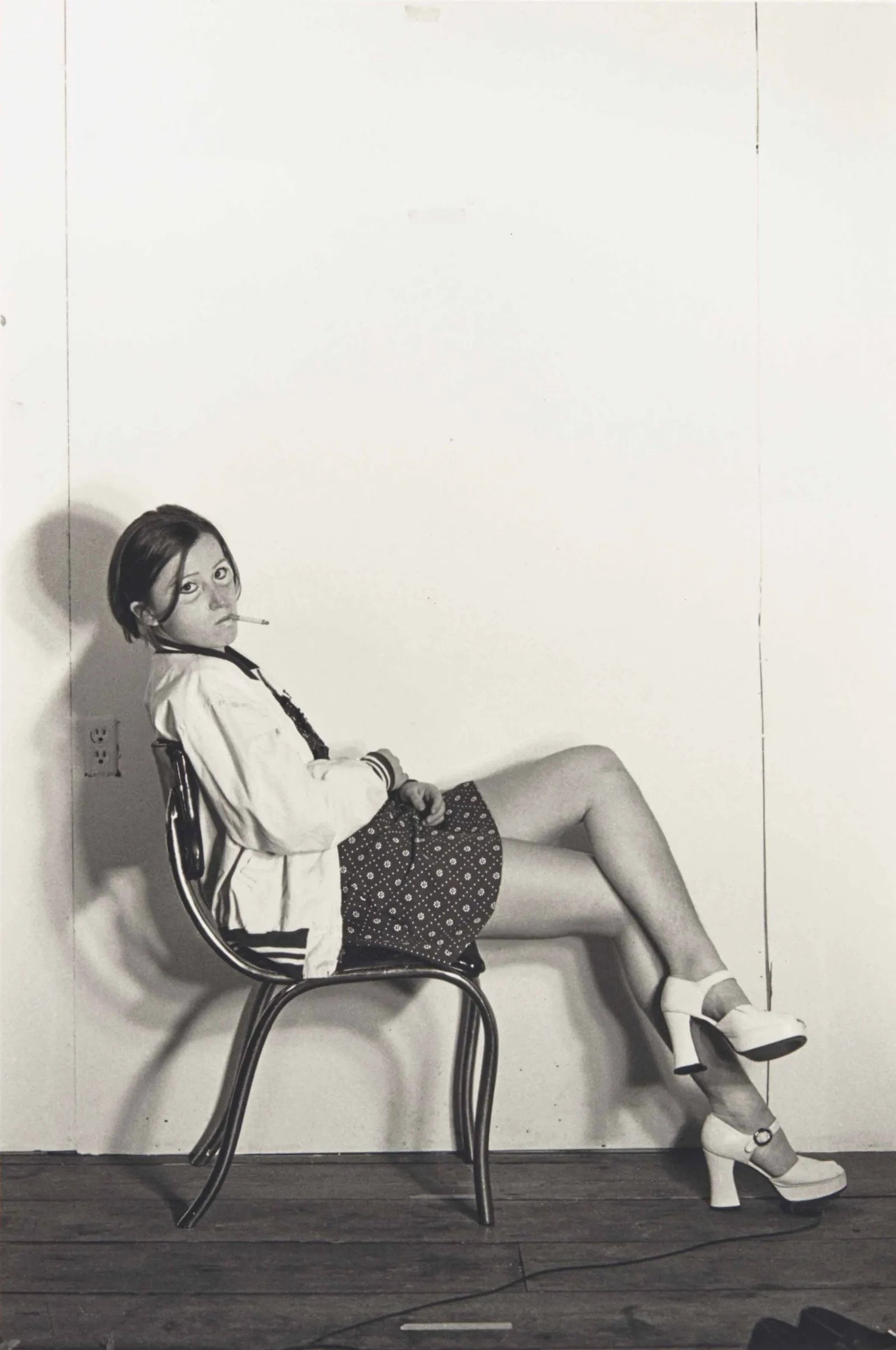

No artist has scrutinised the role of clothes and costume as a cultural signifier more comprehensively than Cindy Sherman. A crucial addition to the Lismore show are ten images from her iconic 1976 (Untitled) Bus Rider series of small black-and-white photographs depicting multiple characters—male, female, Black and white—of all ages and all portrayed by Sherman herself. This landmark body of work, which speaks volumes with the most basic props, poses, clothes and makeup, was not only a prelude to Sherman’s lifelong exploration of gender, self perception and the markers of class and identity, but it has also formed a key inspiration for numerous subsequent artists who continue to mine these themes, including Yasumasa Morimura, Gillian Wearing and Rachel McLean.

Cindy Sherman's Untitled (1976/2000). Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. © Cindy Sherman

Contemporary art has always been central to Rocha’s practice and the artists she has either referenced in her collections, illustrated in publications or exhibited in her shops extend from Pae White and Roni Horn to Robert Rauschenberg and John Constable. Louise Bourgeois has been an abiding influence, with Rocha incorporating her textile patterns into dresses, as well as creating a range of Bourgeois-inspired earrings and even designing shop display units based on her Cell sculptures. The grande dame of visceral psychodramas and bodily provocations is here represented by two sculptures, - the leather-jacketed Janus and an untitled bronze cast of four clasped hands each projecting a severed forearm–both of which are housed in their own separate cell-like space in Lismore’s Round Tower.

Rocha’s parade of girls (girls girls) ranges from big names to recent graduates and all that lies in between; and much of the show’s strength lies in the conversations struck up between its very various elements. The small house that sprouts from one of Bourgeois’s severed arms not only references the claustrophobic hybrid femme-maisons that have cropped up in her work from the 1940s, but here also reverberates in the 20-something British artist Sophie Barber’s giant painting of a pair of pink houses that covers the entire back wall of the main gallery. Teetering precariously on spindly stilts and looking more like an odd couple than two pieces of architecture, his huge dangling tarpaulin-canvas sends out mixed messages about hearth, home and relationships as well as providing a bold backdrop to the show.

Other fruitful exchanges include the way in which the intimate performative intensity of a 1977 self portrait by the late Francesca Woodman corresponds with a nearby collaborative textile piece by young Irish duo Eimear Lynch and Domino Whisker. Here three sepia photographs of a ghostly dancing females are framed in suture-like red stitchwork, which also nods to Louise Bourgeois’s expressively embroidered fabrics. Sian Costello only graduated from Limmerick School of Art and Design less than two years ago, but her small, lush, slightly sinister infanta-girls more than hold their own amidst the photographs of Roni Horn, Cindy Sherman and a glorious resin lip-lamp by the late, great Alina Szapocznikow.

Left to right: Eimear Lynch; Daisy Hoppen; Simone Rocha; Lizzie Ridout; Laura Burlington. Photo: Louisa Buck

With her chosen gang of artist-girls, Rocha presents a highly personal engagement with, and challenge to notions of the female. During the opening weekend there was also an additional, albeit unintentional, performative element offered by the designer and her three-woman team, who, together with Lismore’s current chatelaine and fellow fashion maven Laura Cavendish, Countess of Burlington, cut a dramatic dash as they perambulated through the castle’s halls and gardens, clad in an ever-changing array of Rocha finery. From beribboned heads to bejewelled and sometimes bovver-booted toes, this formidable posse resonated with both the current show as well as many of Lismore’s old master portraits of previous wives, daughters and duchesses, providing living breathing proof—if any were needed—of the perpetual power of girls, girls girls!

• girls girls girls, Lismore Castle Arts, until October 30 2022