China is cracking down on the sale of stolen antiquities, but experts say more structures and resources need to be put in place to help people avoid unwittingly selling looted items.

Since China’s police and cultural heritage administration launched a joint special action over a year ago, around 2,200 cases of cultural-heritage-related crimes have been solved and a total of 58,000 antiquities were recovered, according to an announcement from the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) in September.

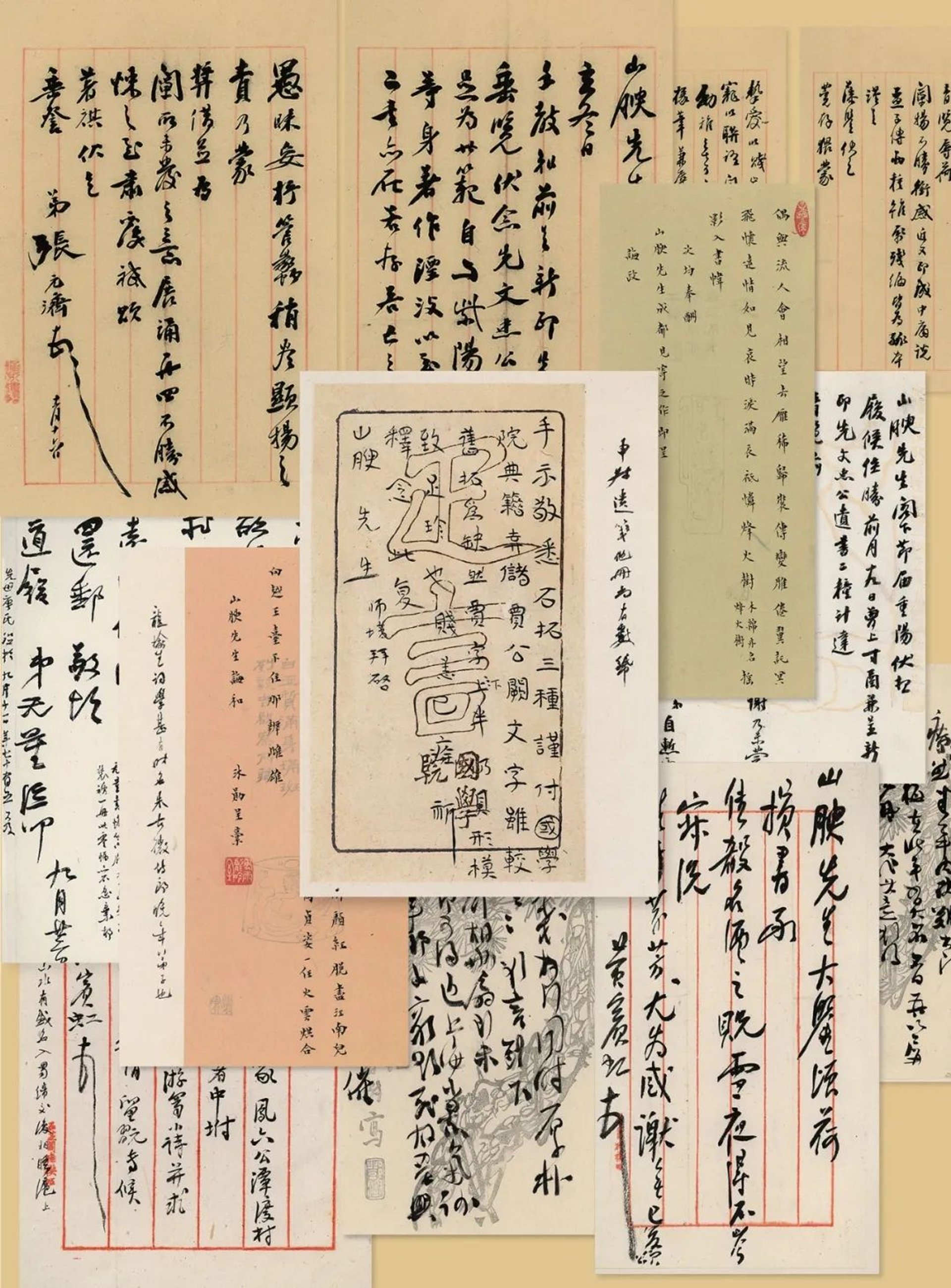

In a press conference last June, an MPS spokesperson pointed to a recently resolved 16-year-long case, involving stolen national treasures sold at auction last year. The case centered on 44 lots of letters by modern Chinese poets, calligraphers, artists, and scholars in an auction at Canton Treasure in September 2020 in Guangzhou city. These items were suspected to have come from Yuyanji, the letter archive of the poet and founding director of the Sichuan Provincial Library, Lin Sijin (1874-1953), and other well-known literati of his era. An important record of local history, the archive had been stored in the library for decades but suspicion was alerted when it was advertised for sale in 2020, with a total estimate of Rmb800,000 to Rmb1.3m (around £91,580 to £148,820)

In China, it is set in law that public institutions (such as the Sichuan Provincial Library) “shall not donate, lease or sell state-owned cultural relics in their collection to any other organisation or individual.” That means that the Yuyanji letters should never have appeared on the market, which begs the question: were the lots for sale stolen, or fake?

The police immediately ordered Canton Treasure to withdraw the disputed lots. Further investigation revealed that the items were consigned by a China-born architect of international fame (their name has not been revealed). The vendor at Canton Treasure had bought the letters at Shanghai Chongyuan auction for Rmb308,000 (around £35,258) in 2005. The seller then was registered as “Liu Decheng”, who also consigned nine other lots to the same sale (five were unsold), all of which were later proven to have come from Sichuan Library collection. One of these, a Tang Dynasty (618-907) Buddhist scripture manuscript, is deemed a Class A national cultural relic.

However, police failed to find any information on Liu on their demographic databases. A more thorough search was carried out, examining relevant transaction records, banking details, phone records and witnesses’ testimony. Finally, a 58-year-old male suspect named Chen (his full name was not disclosed) was confirmed this January.

Some of the letters which were withdrawn from Canton Treasure's auction in autumn 2020

Source: Canton Treasure Auction

According to local media reports, Chen was making a living as an art teacher when police arrested him in January in Deyang, a city around 70km north-east of the crime scene. He admitted having broken into the library’s storage and stealing ten pieces of “antiquities and historic documents” from its collection in December 2004. Between 2005 to 2011, Chen consigned multiple items to auction using the false identity of “Liu Decheng” and he confessed to making nearly Rmb900,000 (around £103,280) in proceeds.

On 10 September 2020, Canton Treasure issued a statement on social media stressing that the auction house had "strictly followed the auction procedures” in terms of “acceptance of the consignment and selection/review of the lots”. The auction house also told state media that the lots were approved for sale by the Cultural Heritage Administration of Guangdong before being advertised—something confirmed by authority’s website.

Xu Wenxi, the general manager of Canton Treasure, told the Yangcheng Evening News that experts did not find any mark or trace on the objects suggesting that they belonged to Sichuan Library; nor did the items appear in the lost treasure reporting system. The system is an authoritative website, to which users can upload information about lost or stolen antiquities for the cultural heritage administration to review. Once a report is verified, it appears as a web page accessible to anyone, as an aid to solving cases. The system has become an essential due diligence tool in China’s antique transactions since it was launched in 2017.

On 13 August 2021, the TV documentary series 天网 (Pinyin: Tianwang) on CCTV-12 explained why the missing Yuyanji documents had not been reported online—for years, the library staff only noticed the missing Tang Dynasty manuscript, while nobody clocked that Yuyanji and eight other items were absent too.

The worrying fact that is highlighted by the Yuyanji case is that, even when Know Your Customer investigations and due diligence are fully performed in accordance with the law, there is still a chance that looted items will slip through the net and appear at auction.

Ray Dong, a former lawyer and the current director of Art Market Research Center, Central Academy of Fine Arts, cites the case of the Library of Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, where the former director, Xiao Yuan, secretly swapped nearly 150 genuine paintings (estimated to be worth over Rmb100m/around £11.5m) in the library’s collection for home-made fakes between 2002 to 2010. Xiao successfully sold most of the originals at auction.

“[Auction houses] shall do their best by all means to prevent [selling any stolen item], but in practice, it’s very hard to achieve it,” Dong says. “What an auction house can do is to strictly report, release, inquire and collect information [about the auction lots]. But it’s impossible to completely avoid such risks and problems.”

Dong adds: “To avoid similar situations in the future, a key step is for public institutions to upgrade their security measures—comprehensive and efficient digital archiving is in urgent need. Although these fields had improved dramatically compared with before, there is still room [for improvement].” He adds that introducing more stringent protocols and laws in this area, and more thorough pursual of criminal investigations would help to make a difference too. “Nowadays, our digital ID are closely crosslinking to contact information and financial account—hence a slimmer chance for people to use fake identities to participate in auction,” Dong says.

According to Chinese state media reports, the stolen antiquities from Sichuan Library have been auctioned and some of them resold a few times to different buyers in Beijing, Shanghai and other places. Yuyanji was the first of the ten items to be returned to the library. This May, an anonymous collector decided to donate the Tang Dynasty manuscript back to the library. These two “national treasures” are finally home after a 16-year-long journey. However, what and where the rest of the stolen items are, and if their current owners are willing to return them, is still uncertain for now.

The criminal case against “Chen” is still being pursued by Sichuan Police, and the court sentence is pending. An information disclosure application, first sent by The Art Newspaper in September 2021, has so far gone unanswered.

This is far from the only case of looted items appearing at auction in China. Zhao Qiang’s 2020 research on auction risk management found that, from 2002 to 2019, at least 23 cases of looted works of art or antiques were discovered for sale at auctions in Bejing, Shanghai, Zhejiang province, Hubei province and Hong Kong (all were withdrawn before the sale). These included a looted Zhang Daqian painting with a high estimate of HK$3.8m which had been entered for sale at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in 2019. Zhao suggests that a “special investigative department” should be set up for such cases, and that current loot recovery legislation needs to be improved.