The 2022 edition of the Whitney Biennial, titled Quiet as It’s Kept, features the work of four Indigenous artists from the US and Canada: Rebecca Belmore, Raven Chacon, Duane Linklater and Dyani White Hawk. While the previous edition of the biennial featured a larger number of Indigenous artists, it was criticised by some for relegating most Indigenous art to less-trafficked corners of the show. The works in this edition are exhibited more prominently and parallel other works in their political, conceptual and visual themes.

“We wanted to create a scenario that was advantageous to each artist but that also created an assembly of voices,” David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards, the curators of the biennial, write in a statement to The Art Newspaper. “Some traditions and histories are shared, while others are keenly unique and specific. It was our job to bring these together throughout the show.”

The curators add: “It is undeniable that ideas like abstraction and conceptualism have always been part of Indigenous cultures; the so-called West has never owned them. The work of these artists redirect and cross wire the idea of influence; they foreground and centre Indigenous voices and visual culture and, in so doing, inflect the future trajectory of what art and its reception can be.”

Installation view of Duane Linklater, a selection from the series mistranslate_wolftreeriver_ininîmowinîhk and wintercount_215_kisepîsim, (2022). Collection of the artist; courtesy the artist and Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver

Duane Linklater, wintercount_215_kisepîsim (2022) and mistranslate_wolftreeriver_ininîmowinîhk (2022)

The Cree artist Duane Linklater has created richly saturated tapestries, what he envisions as non-functional tipi covers, using pigments traditional in Indigenous art, including sumac, charcoal and cochineal. The works will be moved throughout the biennial, allowing repeat visitors to experience them anew. While the works reference aspects of Cree language and cultural elements, they also stand alone as powerful abstract pieces. “Abstraction provided me with self-determination and free will,” the artist writes in a statement. “It was liberating. I don’t find freedom in other forms. People like to have an answer before they have the experience. Abstraction doesn’t offer you that.”

Installation view of Dyani White Hawk, Wopila | Lineage (2021). Courtesy the artist and Bockley Gallery, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Dyani White Hawk, Wopila | Lineage (2021)

The Lakota artist Dyani White Hawk and a team of assistants have created this captivating abstract geometric work that draws on cross-cultural themes. The glass beads used in the work “have become synonymous with Plains artwork but were trade items that came through relationships with non-Native people” in the mid-1800s, the artist explains, offering an exciting new medium for artwork that was previously made painstakingly with porcupine quill. The work aims to highlight the shared histories of Native and non-Native art. “Some of the most famous white male painters who are lifted up as the founders of abstraction were looking to Indigenous art and collecting that art because they recognised the strength and agency and beauty and expertise of that work,” she says. “My work is meant to pull out and honour those intersections.”

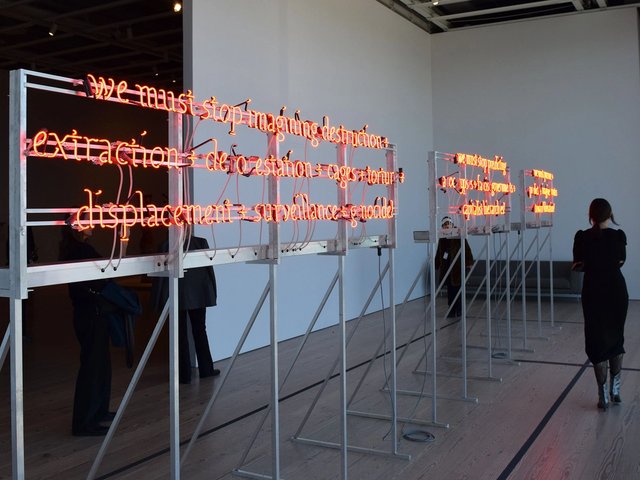

Installation view of Rebecca Belmore, Ishkode (Fire) (2021). Courtesy the artist.

Rebecca Belmore, Ishkode (Fire) (2021)

The Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore—who was the first Indigenous artist to represent Canada at the Venice Biennale, in 2005—made this commanding ceramic sculpture from a sleeping bag cast in clay and surrounded it with an arrangement of empty bullet casings. The work, a critique of the historic genocide and ongoing disproportionate violence against Indigenous people, is a centrepiece of the sixth floor of the exhibition, illuminated from above in the otherwise darkened space. “The work carries an emptiness,” the artist writes. “But at the same time, because it’s a standing figure, I’m hoping that the work contains some positive aspects of this idea that we need to try to deal with violence.”

Raven Chacon, still from Three Songs (2021). Courtesy the artist.

Raven Chacon, Three Songs (2021)

The Diné artist presents an engrossing three-channel video installation in which three Indigenous women sing about the history of a landscape and reference the Trail of Tears, the forced displacement of Native American tribes that took place between 1830 and 1850. “These songs of resistance, with only a snare drum as accompaniment, become a sonic testimony,” the artist writes. They are “an acknowledgement of shared survival, and a healing call in their mother tongues”. The work is complemented by a series of lithographs with geometric designs that abstractedly honour contemporary Indigenous women poets and musicians.

- Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, until 5 September, Whitney Museum of American Art