Just one day after officials from across Europe convened a conference at the Louvre in Paris in February to discuss how to tackle the trafficking of cultural goods, the Belgian National Committee of the Blue Shield issued an open letter condemning the country’s government for quietly closing its police art crime unit a few weeks earlier.

An article in the online publication, The Bulletin, reported how a now-unavailable press release announced that from 1 January, “the theft and trafficking of works of art would no longer be monitored at central level, that the ARTIST (Art Information System) database will no longer be updated, and that the relay of information from and to foreign police, Europol and Interpol will no longer be ensured.”

The decision was seemingly made by the country’s minister of the interior, Annelies Verlinden, following years of uncertainty around the funding of the enforcement’s resources in this area, which had been dwindling since 2015. The minister’s office did not reply to our request for comment.

In its open letter, the Blue Shield, a non-profit international organisation aimed at protecting heritage, claimed the move meant that Belgium no longer respected the 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. Blue Shield’s letter adds: “In its struggle for cultural heritage, the Belgian Committee of the Blue Shield wants more than ever to express strongly its indignation at the disinterest of the different levels of Belgian power and the lack of attention and -concrete resources made available to fight against the illicit traffic of works of art in our country.”

“In my opinion, the locations facing some of the largest cuts are not locations where the problems, which such units address, are minimal,” says Donna Yates, an associate professor of criminal law and criminology at Maastricht University. “In other words, to use the Belgian example, it is a key art market country that has been linked to numerous recent transnational cases of art crime; it isn’t at all an obvious place to cut this type of policing.”

A growing problem?

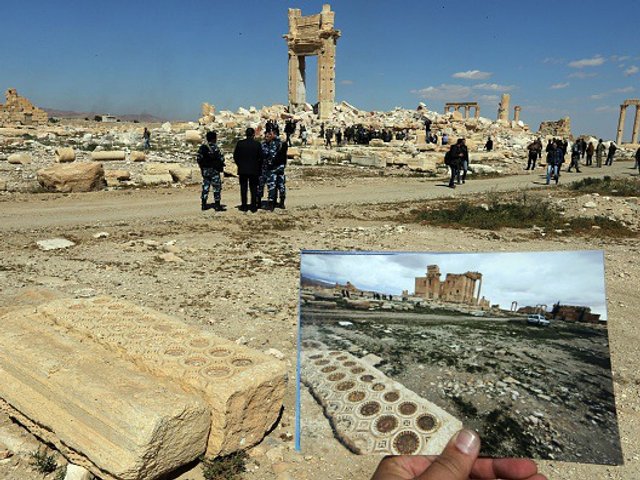

The cutting of Belgian resources also occurred just weeks before the publication of a memo from the French EU presidency outlining an “alarming increase in the destruction of cultural heritage due to armed conflict”. The note reinforced research published last year which suggested that some areas of the crime had been increasing over the pandemic and gives a taster of an upcoming pan-Europe action plan focused on “transparency, traceability and confidence”.

Such claims are backed by recent police investigations, including the pan-European Operation Pandora, which seized more than 56,000 cultural goods over a five-month period in 2020, led by Spanish Civil Guard and involving law enforcement across 31 countries.

Elsewhere, governments are boosting their initiatives, including Germany, which has seen the launch of a new app to support police and customs officials in tackling illicit trade, spearheaded by the Fraunhofer Institute in Darmstadt and part-funded by the government. Some in the art industry itself are also drawing attention to the issue, notably the 12 trade associations that late last year pledged to tackle the sale of artefacts coming out of Afghanistan, following the Taliban’s seizure of power.

Whether such initiatives are undermined by the reduction in enforcement remains to be seen. “Without specialised units, the specialised data collection (and analysis and intelligence that comes with it) is gone,” Yates says. “Without specialised units, there is no one obvious to receive data and intelligence from abroad and pass on what they know. As such, I think that alone is likely to undermine anything being done at a European level.”