Today, 11 March, marks the anniversary of the destruction of Bamiyan’s iconic sixth and seventh century Buddha statues by the Taliban in 2001.

In 2003, the cultural landscape and archaeological remains of Bamiyan Valley were placed on Unesco’s World Heritage in Danger list, providing an opportunity to preserve the area for future generations and the world. Now, 21 years after the Buddhas of Bamiyan—known as Salsal, or the Western Buddha, and Shahmama, or the Eastern Buddha—were blown up, and after countless resources were spent to restore and protect the area over the last two decades, the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan has experts and locals worried about whether what is left of the cherished heritage site can survive amid reports of illegal settlements and activities on listed grounds, excavations and looting.

“We are witnessing a silent explosion in Bamiyan and across Afghanistan. The Taliban will not use explosives to destroy the cultural heritage sites, what they are doing is worse. They are allowing the gradual demise of the Bamiyan Valley and other heritage sites, changing the education system so that history and culture are not taught objectively and arts that are against their beliefs are being stored in museums’ basements and erased from memories,” says Laeiq Ahmadi, a former head of the archaeology department at Bamiyan University.

Since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021, areas around the Bamiyan cliff where the Buddha niches are located have fallen victim to looting, illegal construction and excavations that threaten the complete annihilation of the site. Recent reports suggest the destruction extends beyond the Bamiyan cliff, with the nearby Shahr-i Ghulghulah site suffering similar neglect and mistreatment.

A looted site at Shahr-i Ghulghulah. The door is broken and there is nothing left inside the room. © The Art Newspaper

Located in the centre of the Bamiyan Valley, Shahr-i Ghulghulah, one of the eight sites registered by Unesco in 2003, is a fortified citadel from the sixth to tenth centuries CE situated on a hill. Locals have reported illegal excavations in the area, some over three metres deep around the eastern entrance to the citadel. The site’s archaeological depot has been looted, while other sites have been burnt. The Art Newspaper obtained photographs of the wreckage and eyewitnesses have confirmed the reports.

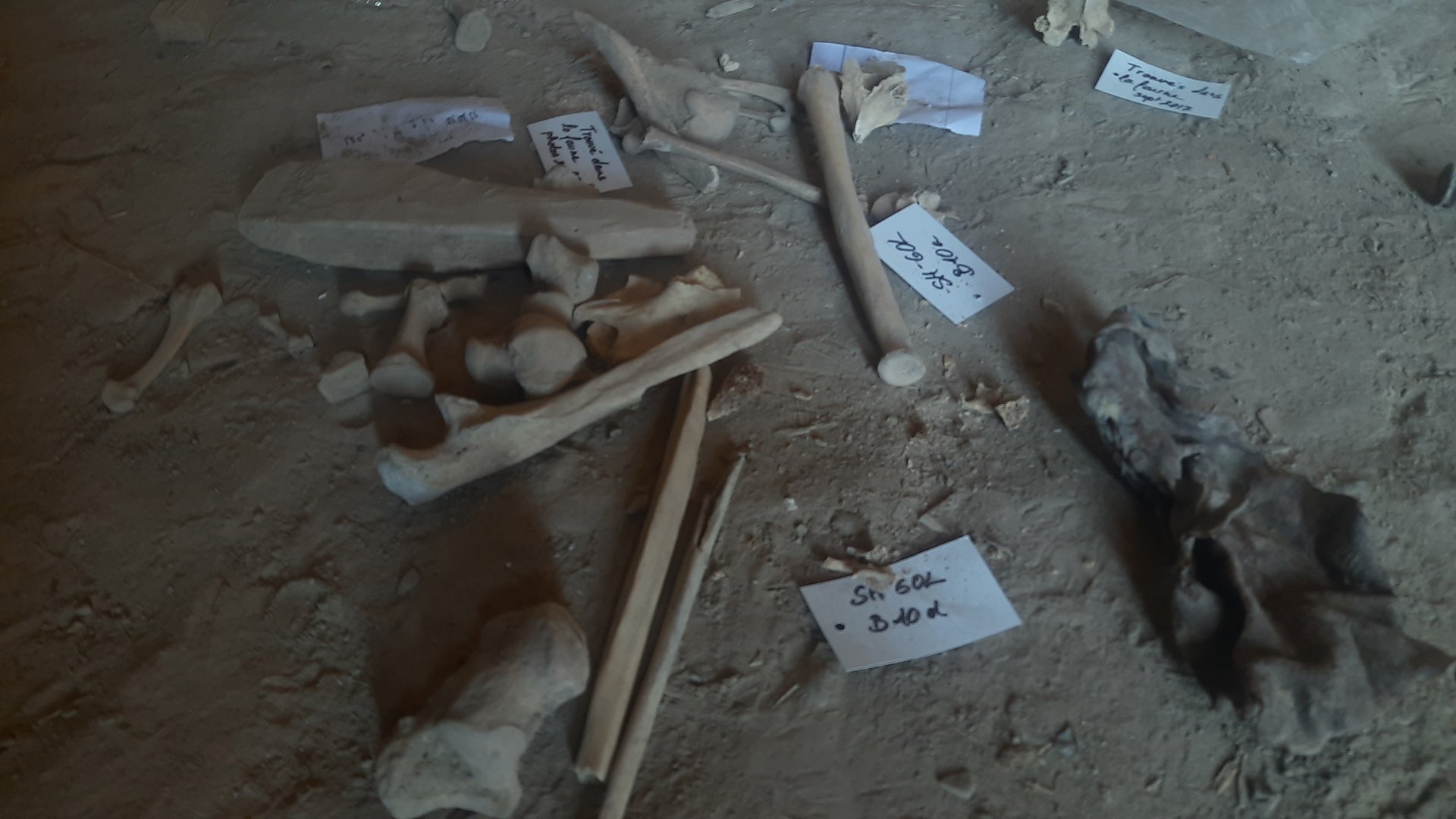

The looting of the depot and other areas is thought to have occurred in the early days of the Taliban’s return to power. However, structures that were once locked and guarded are now completely open, unguarded and accessible to the general public. Tagged items thought to be from archaeology projects, including bones and ceramic pieces, lie broken and scattered around like garbage. While it is unclear if any pieces of great financial value were kept in the Shahr-i Ghulghulah depot, the items are said to have been of great scientific and historical value.

“Even if you lose a small bone that was found as part of the excavations you lose vast amounts of knowledge. The value of an archaeological piece depends on what answers it provides, you cannot put a price on archaeology,” says Ahmadi, who spent around ten years working in Bamiyan.

Tagged items including bones and ceramics from archaeology projects can be seen scattered around inside the looted Shahr-i Ghulghulah depot. The room was once locked and guarded but is now accessible to anyone. © The Art Newspaper

A number of experts familiar with Bamiyan archaeology projects confirmed that the most recent project in Shahr-i Ghulghulah was carried out by the French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan (DAFA) around 2019. Ahmadi believes the project was trying to establish how many historic eras were present in the ancient citadel, which is understood to have been raided during Chengiz Khan’s reign, “because to date there is no concrete research on this area”.

DAFA had not responded for a request to comment at the time of publication.

The Art Newspaper reported in February that illegal excavations around the Western Buddha niche, combined with rapid unplanned developments in the area, such as a coal loading depot that has been set up in front of the Buddha cavity, and environmental factors were contributing to the complete destruction of the Bamiyan cliff and its surrounding area.

“The sad truth is at this rate there will be nothing left for the future generations. I mean perhaps even the next two generations will have lost all this history and culture,” says Ahmadi.

Two masterplans but nobody at the helm

“This is the consequence of having abandoned the area as we did,” says Mirella Loda, Bamiyan’s strategic master plan project coordinator, the director of the masters degree program in geography, spatial management, heritage for international cooperation at the University of Florenceand director of the Laboratory of Social Geography, which she founded in 2005. “This is the consequence of this situation where we, as Western countries, have not decided yet what to do with the area [Afghanistan]. And Unesco is waiting for Western countries to decide because Unesco cannot actually intervene in any case without donors.”

A cultural masterplan was put in place in 2007 in consultation with Unesco and implementing partners, which served as a guide to Bamiyan’s urban development until, in 2019, a strategic master plan was developed by the University of Florence, Afghan Ministry of Urban Development and Housing, Bamiyan Governorate, Bamiyan Municipality and Bamiyan University.

“The cultural master plan was an inventory of the cultural resources,” says Manfred Hinz, one of the strategic master plan’s authors and a professor for intercultural studies at Passau University in Germany. “Our plan is an urbanistic tool for urban development, which is broader than the cultural map recognised 15 years ago. Now of course it is all gone. It is completely out of control.”

Unsorted materials scattered inside the looted Shahr-i Ghulghulah depot © The Art Newspaper

Some of the solutions the strategic master plan recommended to protect the cultural heritage sites while supporting the area’s economic development included a designated hotel district area to protect the sites from tourists, a preferred location for construction of a bypass road, recommendations on housing development and even suggestions for empowering the growth of local culture. However, there are now local reports of at least one hotel planned for construction on listed land and the road that runs through the valley that was previously restricted to heavy vehicles has become the area’s main transportation route.

“The Ministry for Urban Development is entirely dismantled,” Hinz says. “The first and second Taliban cabinet did not even have a minister for urban development, now they have one since a few months [ago], but the local offices are entirely non-existent, so the situation is completely out of control. There is no control on who builds what, where. Looting of course is not a new phenomenon, neither in Afghanistan or elsewhere.”

Many local experts and collaborators who worked for the previous government fled the country or are in hiding for fear of retaliation by the Taliban. The lack of qualified personnel worries experts who fear the new rulers do not have the know-how to protect the sites.

“It is not a problem of political difference, it is a problem of different language, different views of what is there to do, what is not to do? What is heritage? What should be done with heritage? What is a masterplan? I am afraid they don’t know what an urban planning tool is,” Loda says.

Hinz stresses the importance of Bamiyan for Afghanistan and the world because it is the farthest to the west that Buddhism reached, and it was also a very important site on the commercial route to India and China.

“The literature on the history of Bamiyan is library-filling. You can spend your life on it and very much is still unknown in fact. There is no comprehensive book on the history of Buddhism in Afghanistan for example,” says Hinz.

“It is as important to preserve the cultural landscape as to preserve the archaeological sites. You cannot protect a landscape as a museum. You have to protect the landscape as something that is changing but has to change according to some rules, not without rules,” says Loda.

A de-listing risk

The Taliban’s neglect of the region’s cultural heritage could have dire implications for Bamiyan standing as a Unesco world heritage site.

“Bamiyan is on the list of ‘in danger’ [sites], so if you want to keep it out of danger and in the normal list you need a management plan for the area,” Loda says. “For the management plan it is crucial to have a cultural masterplan, to have a strategic masterplan, to have these tools that help with how the area develops and so on. Without these tools Bamiyan cannot be removed from the danger list.”

Tagged items including bones, and ceramics from archaeology projects are seen scattered inside the looted Shahr-i Ghulghulah depot. © The Art Newspaper

Loda adds that if Bamiyan were to be removed from the Unesco world heritage list it would be another in a series of losses. “We already had one [defeat] last August, a military one. This would be a cultural defeat. A lot of work, a lot of energy, a lot of money spent for nothing during 20 years,” she says.

“My expectation is that Bamiyan and [the 12th century building] Minaret of Jam will remain on the Unesco list in danger because to cancel them altogether would be a political signal, which Unesco would not want to send, the signal that we give up Afghanistan altogether. I think it would not be a good idea to do so and I think Unesco will not do it, I hope at least,” Hinz says.

As of press time, Unesco had not responded to a request for comment.

Worries about how illegal developments and activities will affect Bamiyan’s future are not limited to archaeologists and cultural experts. Local residents, especially those who have benefitted from tourism, share those concerns.

“Bamiyan has a certain beauty; with the greenery on one side and water on the other side. But unfortunately now with the containers, the coal depots and stores it has really gone backwards. Coal is black so you can imagine what it is doing to the area,” says a local hotelier. “When the scenery and the landscape is affected, less people will visit, of course it will affect our business. It is a circle; our supplies for our guests come from the Bamiyan bazar, so if we don’t have guests they will suffer too. One of our main sources of income is tourism. Without it I don’t know how we will survive.”

Prior to Taliban’s rise to power, the Bamiyan sites were guarded by a designated wing of the military police, 012 division, which reported to the Ministry of Information and Culture.

“The governor of Bamiyan and the province of Bamiyan, with the help of Ministry of Information and Culture, were charged with registering all the sites and protecting each one of them,” Ishaq Mowahidi, the former head of Bamiyan’s Ministry of Information and Culture, says from the US, where he was evacuated in August 2021 for fear of retaliation by the Taliban or their supporters.

According to Mowahidi, under 012 division’s supervision anyone who tried to build on listed lands was warned not to proceed. If they refused to stop, legal action was taken against them.

“Protecting Buddhas and statues is not possible in Taliban ideology, they are extremists,” says Mowahidi. “But I ask them, for their government to build a mechanism in place that allows for the protection of the cultural heritage sites for the values of the world, even if protecting the sites is against their beliefs.”

Contacted for this article, Bamiyan’s Taliban governor declined to comment.

A burnt site at Shahr-i Ghulghulah in an area that was previously locked and guarded. © The Art Newspaper

“The Taliban claim they are different from 20 years ago, but their negligence in looking after these sites shows that they have not changed at all. This shows they are still unwise and against humanity,” says Mowahidi.

Those sentiments are shared by many Afghans who have worked in the field of arts and culture in Bamiyan, like Zahra Hussaini. Since 2016 Hussaini, an archaeologist, artist, women’s rights advocate and cultural activist, had organised “A Night with Buddha”, an annual cultural programme that took place on the anniversary of the Buddhas’ explosions. The event sought to raise awareness among locals about the importance of protecting Bamiyan’s cultural heritage sites.

“I don’t have any expectations from the Taliban [to preserve Bamiyan cultural heritage sites] because this group has shown that it is a founder of terrorism and it does not care for culture, science and history,” Hussaini says from Stockholm, where she moved in October 2021 and is now an artist in residence at the International Cities of Refuge Network.

Hussaini says as part of A Night with Buddha, participants performed a protest walk between the two Buddha niches carrying lanterns. The protest was a reminder of what had taken place in 2001, so that history would not repeat itself. She says initially there was some resistance from locals who viewed the event as celebrating idolism, but over the years even the religious clerics who had been among the programme’s harshest critics began taking part in the memorial.

This year, for the first time in the nine years since the event’s inception, it will not be held in Bamiyan Valley. Instead Hussaini has organised a version of the event in her adopted hometown, at Stockholm’s Kulturhuset theatre.

“It is important to continue with the event,” she says. “This year is a reminder to the world to not forget about Afghanistan, where cultural heritage sites such as Bamiyan are in an extremely vulnerable and fragile state.”