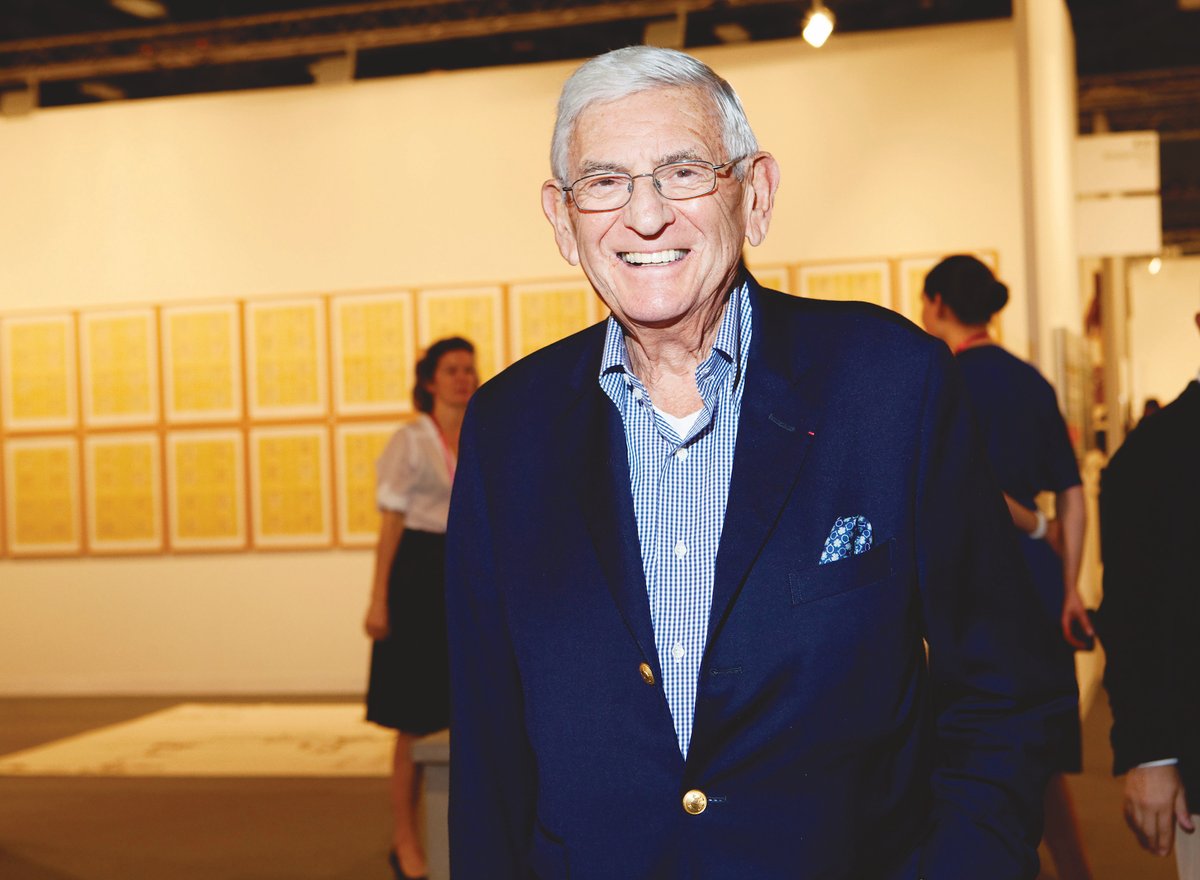

For decades, one man stood astride the Los Angeles art world like a colossus, helping to build and shape its cultural institutions. Many patrons fulfil their roles by collecting art, making donations and attending plush fundraisers. Eli Broad certainly did those things, but he did so much more.

When he died last April after a long illness, many wondered who could take his place. Probably no one; his accomplishments were unparalleled. He was a founding member of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) Los Angeles, a major funder of the Broad Contemporary Art Museum (part of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, or Lacma), and the founder and funder of The Broad, the museum that became the repository of much of his esteemed collection.

He also had a grand vision for Los Angeles, his adopted city. At a MOCA fundraiser in 2010, he declared, “There is no question that Los Angeles has become the contemporary art capital of the world. And MOCA and Grand Avenue are at the heart of our capital.” Five years later, his own museum opened alongside MOCA and Walt Disney Concert Hall—two institutions he helped stabilise amid financial difficulties—along the reinvigorated Grand Avenue corridor in downtown Los Angeles.

A museum for the future

Broad’s philanthropy was not limited to art; he also funded education and medical research. But today he is best known as an art patron due to The Broad. In 2019, more than 900,000 people visited the 120,000 sq. ft museum, designed by Elizabeth Diller of Diller Scofidio + Renfro with a striking creamy white honeycomb cladding.

The museum is free and attracts many young visitors. Its entryway has become a model for other museums: there is no admissions desk, and visitors are checked in by staff toting digital tablets. There are two levels of galleries, with a middle floor for offices and partially visible storage. Gallery attendants guard the works but are also trained to engage visitors in conversations about them.

Currently, a special exhibition celebrating Eli and Edythe Broad’s last ten years of collecting, Since Unveiling: Selected Acquisitions of a Decade, is on view (until 3 April). It includes pieces by artists the Broads collected for years, such as John Baldessari, Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo. One room is devoted to the Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson’s nine-channel video installation The Visitors (2012), which is in a way about collective and individual creative experiences. There are also a significant number of works by African American artists, including Glenn Ligon, Kerry James Marshall and Kara Walker, reflecting a deliberate focus for the collection.

“The last three to four years of collecting, over 50% of our acquisitions have been by artists of colour, and mostly by African American artists within that group,” says Joanne Heyler, the founding director of The Broad. “Given the struggle for racial justice and so many social issues that are urgent, [those are themes] I want to continue to strengthen in this collection.”

Heyler has worked closely with the Broad collection since 1994 and attributes its strength to her late boss’s unflagging curiosity and foresight. From early on he wanted to collect like a museum—in depth and in a disciplined manner. “He did recognise that for this museum and the collection to remain vital, we would have to keep collecting after his lifetime,” she says. The Broad collection numbers around 2,000 works and continues to add between 25 and 50 works a year.

When Broad was alive, he and Heyler would discuss acquisitions together, although the final decision was always his. Now she guides the acquisitions process, sometimes in consultation with the museum’s two curators, and occasionally with Edythe. The museum has a board but no acquisitions committee.

Joanne Heyler now guides the museum’s acquisition process, having worked with Eli Broad on acquisitions for years

Photo: Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images

Heyler will not reveal The Broad’s acquisitions budget—it is still a private museum, after all—but she says the overall annual budget is $16m, which is provided for through established funds. Not having to worry about fundraising is a blessing, she adds. “It allows me to focus on not only the collection but also really on visitors, which is one of the main places my heart lies. I really want this museum—which lines up so fortuitously with Eli’s desire for the museum—to be popular and appreciated.”

Broad’s beginnings

Trained as an accountant, Eli Broad moved to Los Angeles in 1963 and made a fortune building tract homes and selling insurance. He often credited his wife for being the family’s first collector. When he caught the collecting bug, he started to visit galleries and fairs, and do studio visits with artists who interested him.

“From the beginning, just buying art wasn’t of great interest,” he said an interview just before The Broad opened in 2015. “Collecting is really a learning experience—it’s a way one can broaden the way you can view the world.” He added, “Life would be boring if I spent all my time with lawyers, accountants and bankers.” He especially enjoyed meeting artists “who have a different view of what’s happening in society and the world than other people”.

“[Eli] immediately saw how important and powerful Jean-Michel Basquiat was”

One of the gallerists he often bought from was Larry Gagosian, whom he met in the late 1970s. Gagosian remembers an early visit to the Broad home in Brentwood, then full of works by modern masters including Joan Miró and Alexander Calder, when he realised the man was a serious collector. Later Broad’s tastes moved to living artists and Gagosian introduced him to Jean-Michel Basquiat. “To Eli’s credit, he immediately saw how important and powerful this artist was,” he says. The Broads eventually built a significant collection of Basquiat paintings, and bought many other works from the dealer, including pieces by Jeff Koons, Richard Serra and Andy Warhol.

Broad was known as an astute businessman and tough negotiator, skills that served him well as a collector, too. “I’ve never met a collector who likes to overpay,” Gagosian says.

From dealmaker to patron

A number of artists benefited from Broad’s steadfast patronage over the years. He famously helped Koons when the artist was in a financial pinch, pre-ordering works from the Celebration series that were not yet made. They reportedly ended up costing much more to fabricate than Koons had estimated, and Broad agreed to provide additional funding.

A more recent favourite was Shirin Neshat, the Iranian-born artist who came to the US to study and ended up staying after the Islamic Revolution. Her photographic and video work deals with exile, displacement and the oppression of women in patriarchal societies. In late 2019, the museum hosted the 30-year survey, Shirin Neshat: I Will Greet the Sun Again, and Broad came to meet her in the gallery.

“He greeted me with a big smile,” Neshat writes over email. “Although frail, and clearly in physical discomfort, he studied every image and began to ask questions. What was my process? How did I find these diverse characters in New Mexico? I tried to keep my answers short, knowing that he was a busy man and likely in pain, but he appeared to be in no rush and fully present.”

At the end of their meeting, he rose from his wheelchair and embraced her, then asked, “Shirin, do you remember the first time we met?” She didn’t, but he did—at a party at his beach house after he acquired her 2001 video installation Possessed.

“Broad’s legacy is enormous and needs no explanation,” Neshat writes, “but what he left behind for me as an artist is his kindness, passion for art, wisdom, intelligence and, most of all, his humanity.”