A Dutch auctioneer is due to publish the first catalogue raisonné of Banksy’s street pieces in early April, just weeks after his auction house will offer three murals by the British street artist with a combined value of around €700,000.

The publication has not been authorised by Banksy, but features nearly 1,000 murals painted over the course of his 25-year career. Of these, around 300 have appeared on Banksy’s website or in books he has published, according to the catalogue’s creator, Richard Hessink, who owns Hessink’s auction house in Amsterdam.

However, this is no ordinary catalogue raisonné. According to the International Catalogue Raisonné Association’s (ICRA) website, “in setting out an artist’s entire oeuvre a catalogue raisonné de facto authenticates the works”. But Banksy’s studio Pest Control rarely, if ever, authenticates his street works, stipulating they are “not intended for resale”. The artist often claims authorship of his murals on his website, though there is no archive and little photographic documentation of Banksy’s early murals exist. Some of the earliest works in the catalogue raisonné date back to 1995-96 when he would paint freehand, before developing his trademark stencil style around the turn of the millennium.

Hessink says his reasons for compiling the publication are altruistic; not least because the vast majority of Banksy’s street pieces—around 75%, he estimates—have been destroyed, whitewashed or tagged over. “First and foremost, Banksy is a street artist,” the auctioneer points out. “Over the past 25 years, he has painted in Timbuktu, Havana, New Orleans, Paris, you name it […] the few that remain form the nucleus of Banksy’s legacy.”

Hessink first started auctioning Banksy murals in January 2021, selling—among others—two pieces which Banksy had painted in Liverpool during the 2004 biennial. The condition of the works, which sold for the hammer prices of $227,742 and $242,924, was described as “authentic”, though neither came with a certificate of authenticity.

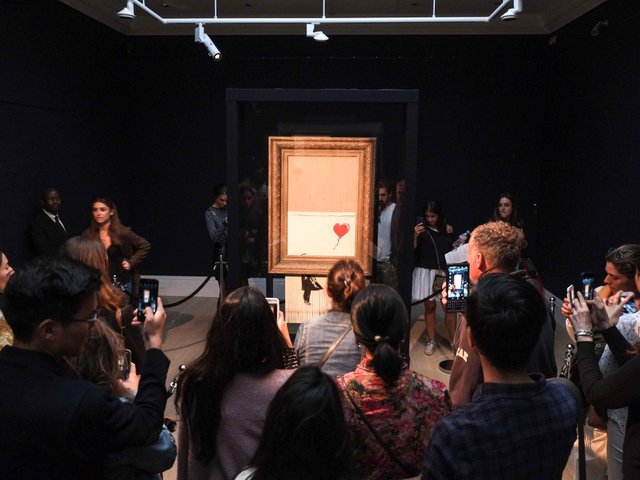

Banksy's Radar Rat, which will be included in the Hessink's auction next month

Courtesy of Robin Barton

Since then, Hessink has offered 17 pieces painted on metal, plywood and concrete, of which just four have gone unsold. He is transparent about the lack of authentication, saying that people are instead “buying a piece of art history, which one day might be worth something”.

On 16 March, a further three murals will be offered in Amsterdam, including Love Plane (2011, est €200,000-€250,000) which was created in Liverpool and Radar Rat (est €150,000-€200,000)—the latter was commissioned by the owners of the now defunct Ocean Rooms nightclub in Brighton in 2002. Two other works from the Ocean Rooms were retrospectively authenticated by Pest Control—one of them, Laugh Now, sold at Bonhams in 2008 for £228,000 with fees.

Hessink says there are plans to launch sales in London next year, the first of which is due to include 12 or 13 of “the most famous” of Banksy’s pieces.

So is there a conflict of interest for Hessink to be compiling a catalogue raisonné—after all, such a compendium could help establish a more official market for Banksy’s outdoor works?

The ICRA’s website notes that “the author/editor(s) of [a] catalogue raisonné should ideally have no financial interest in the works being catalogued”, though, the association adds, “in practice this is sometimes not the case”.

Jon Sharples, an art and intellectual property lawyer with Canvas Art Law thinks any reader of a catalogue raisonné compiled by “somebody who has a direct commercial interest in its contents being accepted and acted upon could perhaps be forgiven for a certain amount of scepticism in the face of an apparent conflict of interests”. But, he adds: “If a catalogue raisonné is ‘reasoned’ in the true sense of the word and amounts to a rigorous, balanced and good faith examination of all of the available evidence, including that which points the other way, then there is no reason such a publication could not become a persuasive and credible authority on the matters it relates to.”

Pest Control did not respond to a request for comment, but Sharples identifies a potential hurdle if Banksy were to assert his moral rights over the publication’s contents. He says: “In theory, Banksy is able to assert his moral rights in relation to his street works. He could exercise his right to object to a false attribution on one of two grounds, namely (1) it wasn’t by him in the first place; or (2) it was originally by him, but has been modified such that it no longer reflects his original intent, for example, it has been cut out from the wall.”

However, just as Banksy lost out on recent trademark cases due to him insisting on his anonymity (copyright can only be enforced if the author is known), Sharples says the artist could face the same dilemma if he ever wanted to enforce his moral rights over his murals—“he’d have to identify himself; notwithstanding the fact that his identity is in fact widely known in the art world”.

Apart from the medium, scale and setting, the biggest difference between Banksy’s indoor and outdoor works remains price—hardly surprising without authentication. The dealer Robin Barton, who has sold around a dozen of Banksy’s street pieces since 2007, describes the “pricing anomaly” as a “monopoly”. He says: “Pest Control are using the instrument of authentication to artificially suppress the Banksy street art market”, which, he adds, is “disingenuous given he has built an international reputation as a street artist”.

The murals Barton has sold range in price from around £250,000 to $1.1m for Slave Labour. The majority have gone to US collectors, including the owner of an unidentified American football club who bought Stop and Search and Wet Dog (for $420,000 and $350,000 respectively), works which were both removed from the West Bank and transported 8,750 miles to Miami.

Barton says of the sales: “I made it very, very clear to all of them, with the exception of the first one I sold that they will never get Pest Control certification for these works. I tell them: ‘You are spending the money, you’re not investing the money. Unless you look at how things work out in the long game’.”

However, Sharples believes the market for Banksy’s outdoor works is unlikely to be affected by the publication of the catalogue raisonné. “Anything that helps build up the factual picture of what actually happened and when in relation to those objects is surely to be welcomed by potential buyers,” he says. “But we should be clear that this is a market for ‘artefacts with a story’ and not ‘authenticated artworks’, which is already reflected in the steep discount these works trade at when compared to accepted works—and I wouldn’t expect that to change.”