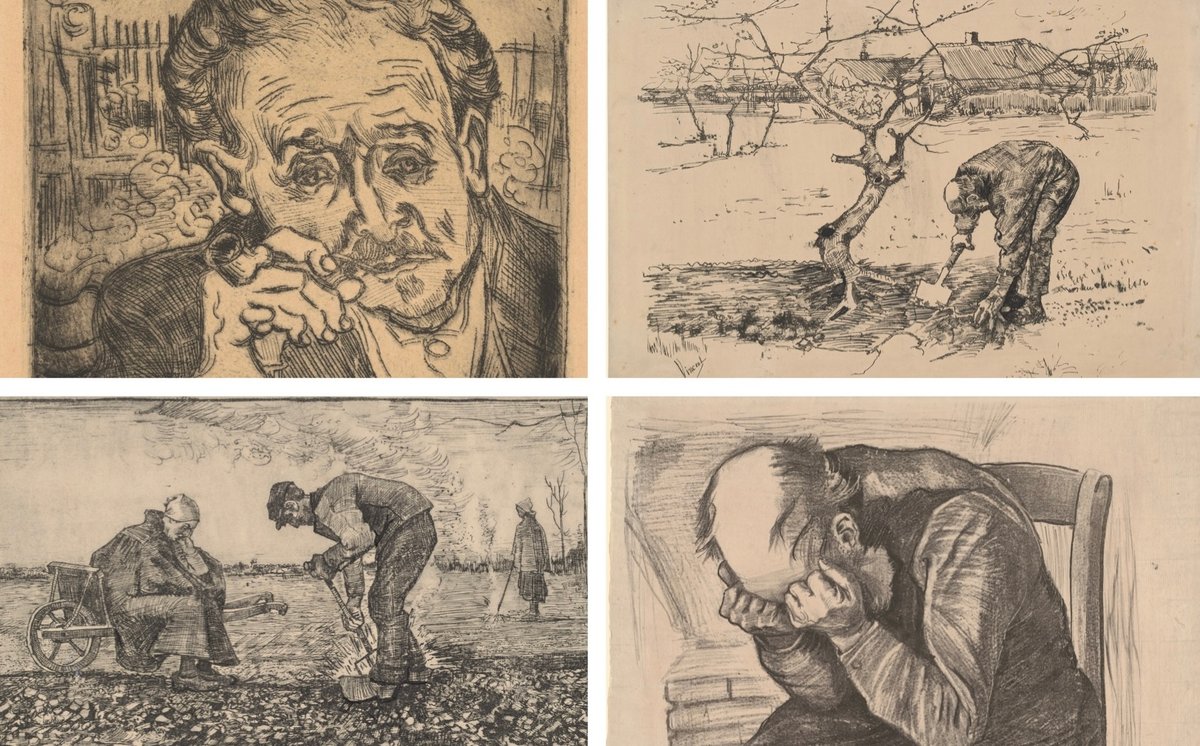

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has quietly bought a set of nearly half of Van Gogh’s prints in a single purchase, we can exclusively report. They come from a Minnesota collector who acquired the three lithographs and an etching in the early 2000s.

The lithographs are very rare and only between four and eight examples of each survive, with most in European museums. None of the three lithographs are represented in any other US museum. Altogether Van Gogh made prints of only ten subjects, so the Met has in one swoop acquired nearly half of them.

The Met’s acquisition was arranged through Christie’s, acting on behalf of the Minnesota owner. The New York museum is keeping the seller’s name confidential, at their request. The prints will be unveiled in a display during the summer.

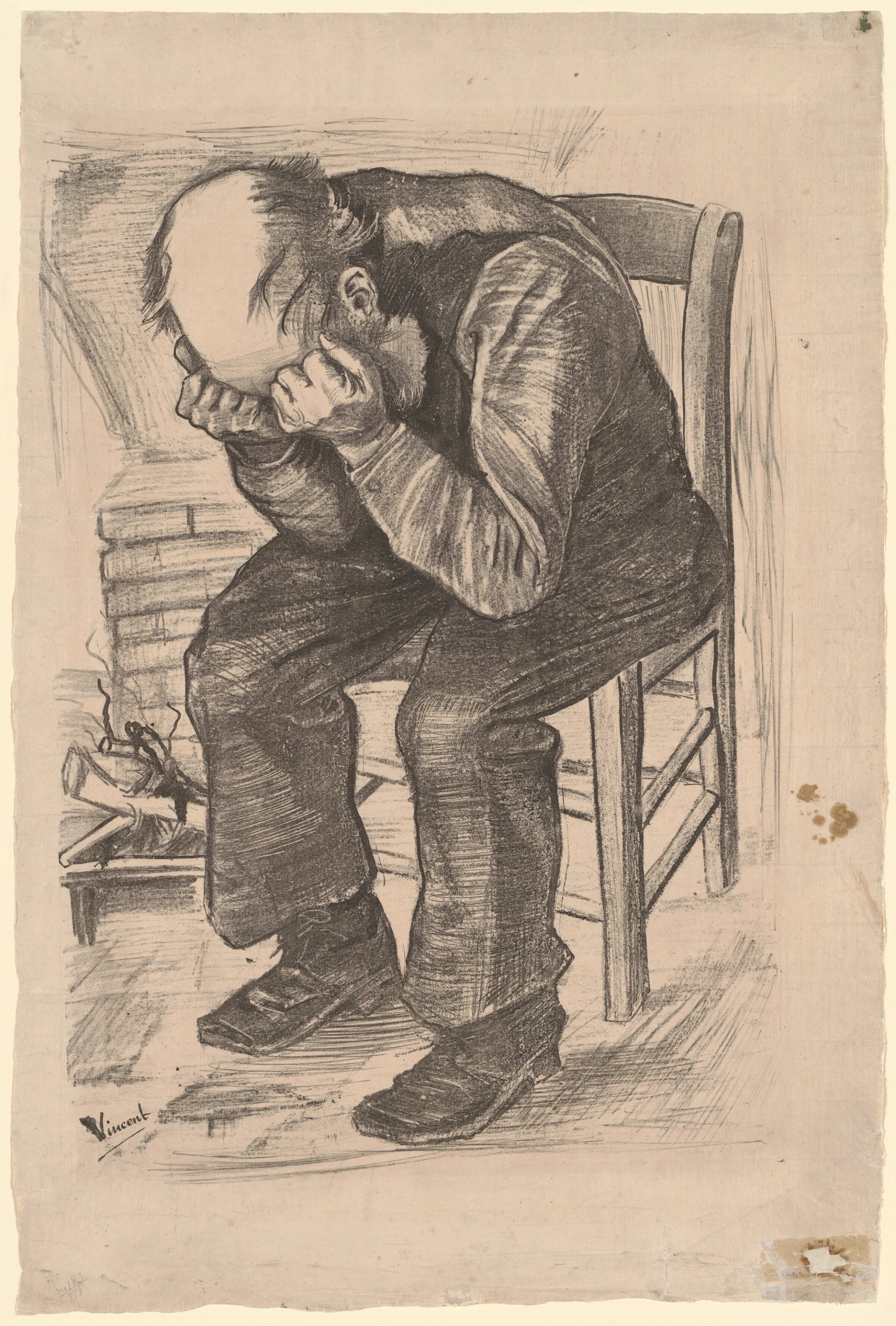

Van Gogh’s At Eternity’s Gate (November 1882) Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Van Gogh’s first prints were made in November 1882, while he was living in The Hague. These include At Eternity’s Gate, which is part of the group acquired by the Met. This is a particularly interesting lithograph, since on another example of the print the artist added the title in English with a pencil.

Vincent had probably intended to use At Eternity’s Gate in his quest to seek work from the publications The Illustrated London News or The Graphic. The location of the inscribed example may come as a surprise: it is at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

The Met’s newly acquired example has pinhole damage in the corners. Van Gogh would casually pin works to the walls of his accommodation, so this print could well have been pinned inside the small apartment in The Hague that he shared with his lover Sien Hoornik.

Four years later, Van Gogh gave this example of the print to his Australian friend, the Impressionist artist John Peter Russell. This was probably in part exchange for Russell’s powerful Portrait of Van Gogh (1886).

Van Gogh’s Burning Weeds (July 1883) Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

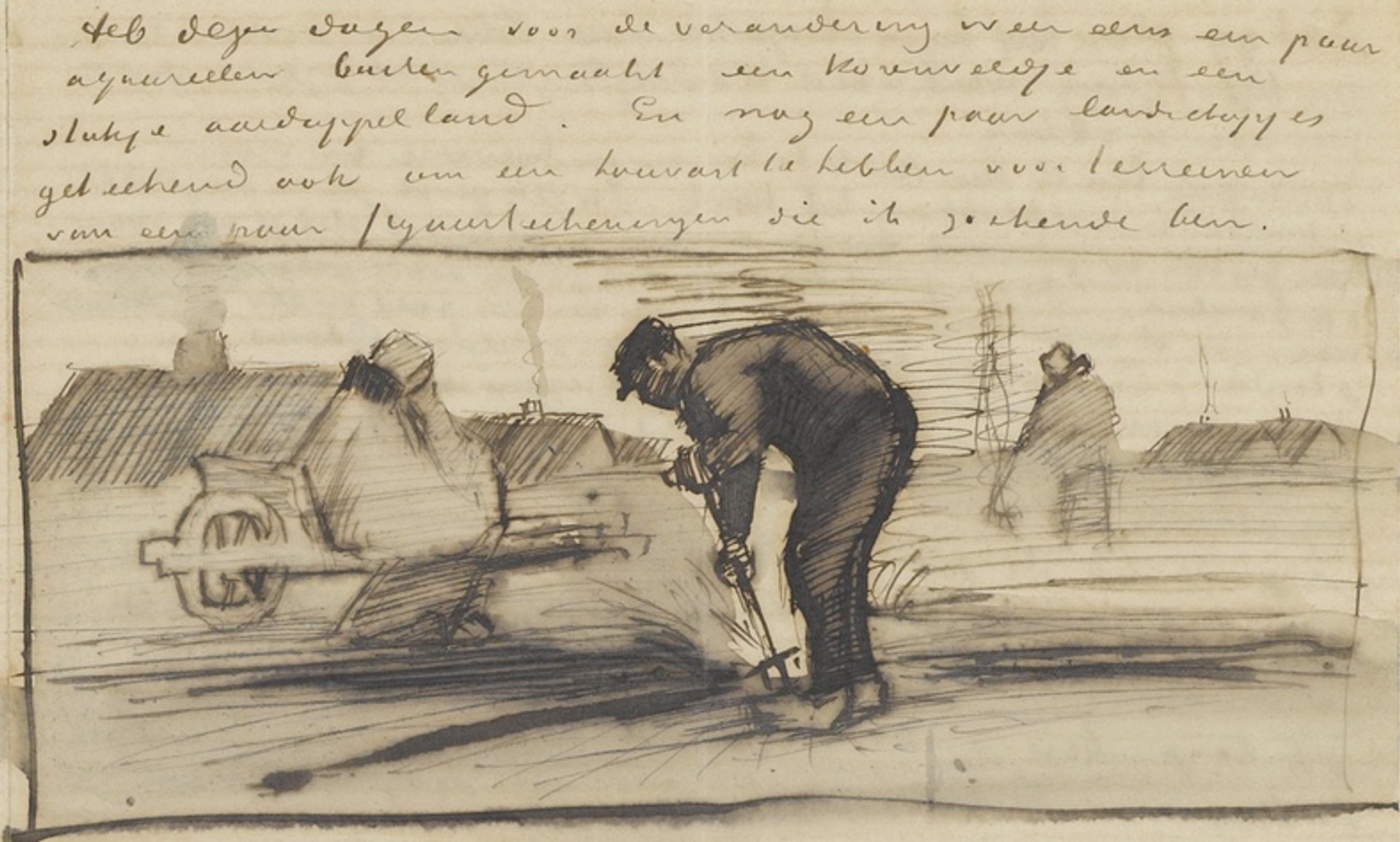

Burning Weeds (July 1883), another of the Met’s acquisitions, was done the following year and depicts a rural scene on the outskirts of The Hague. Its subject matter and style reveal Van Gogh's admiration for the mid-19th century French artist Jean-François Millet, famed for his images of peasant life. Vincent had included a preliminary sketch in a letter to his brother Theo.

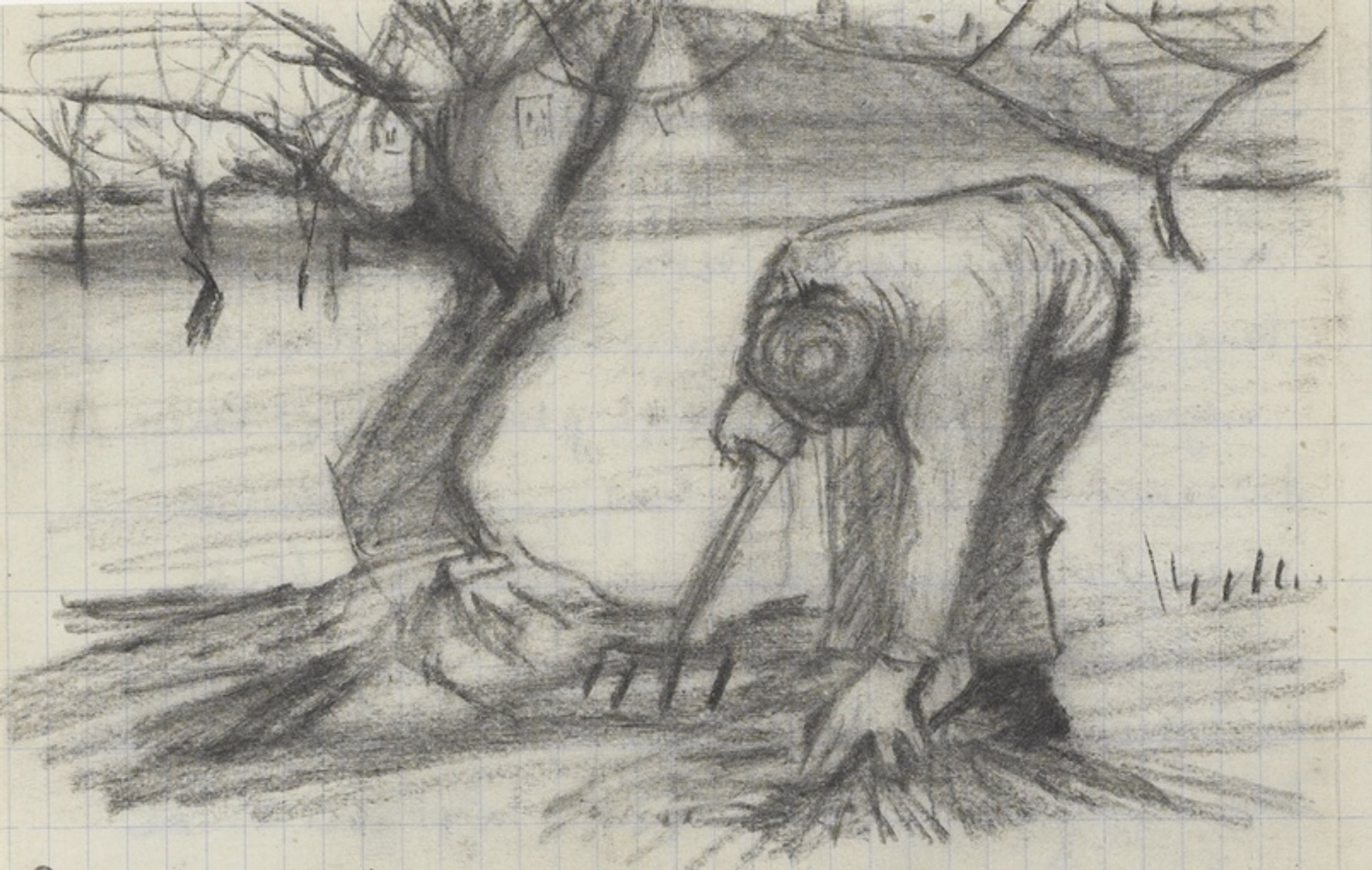

Vincent’s sketch Burning Weeds in his letter to Theo, around 11 July 1883 Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Van Gogh had some difficulties in making the lithograph and touched up the Met’s version of the print with ink to strengthen further details. This is particularly visible on the actual print (but less so in reproductions) in the area around the man’s clogs.

The Met’s example was sold by Vincent’s nephew in 1930. After passing through several collections it was auctioned at Sotheby’s in 2003, going for £252,000 to the Minnesota buyer.

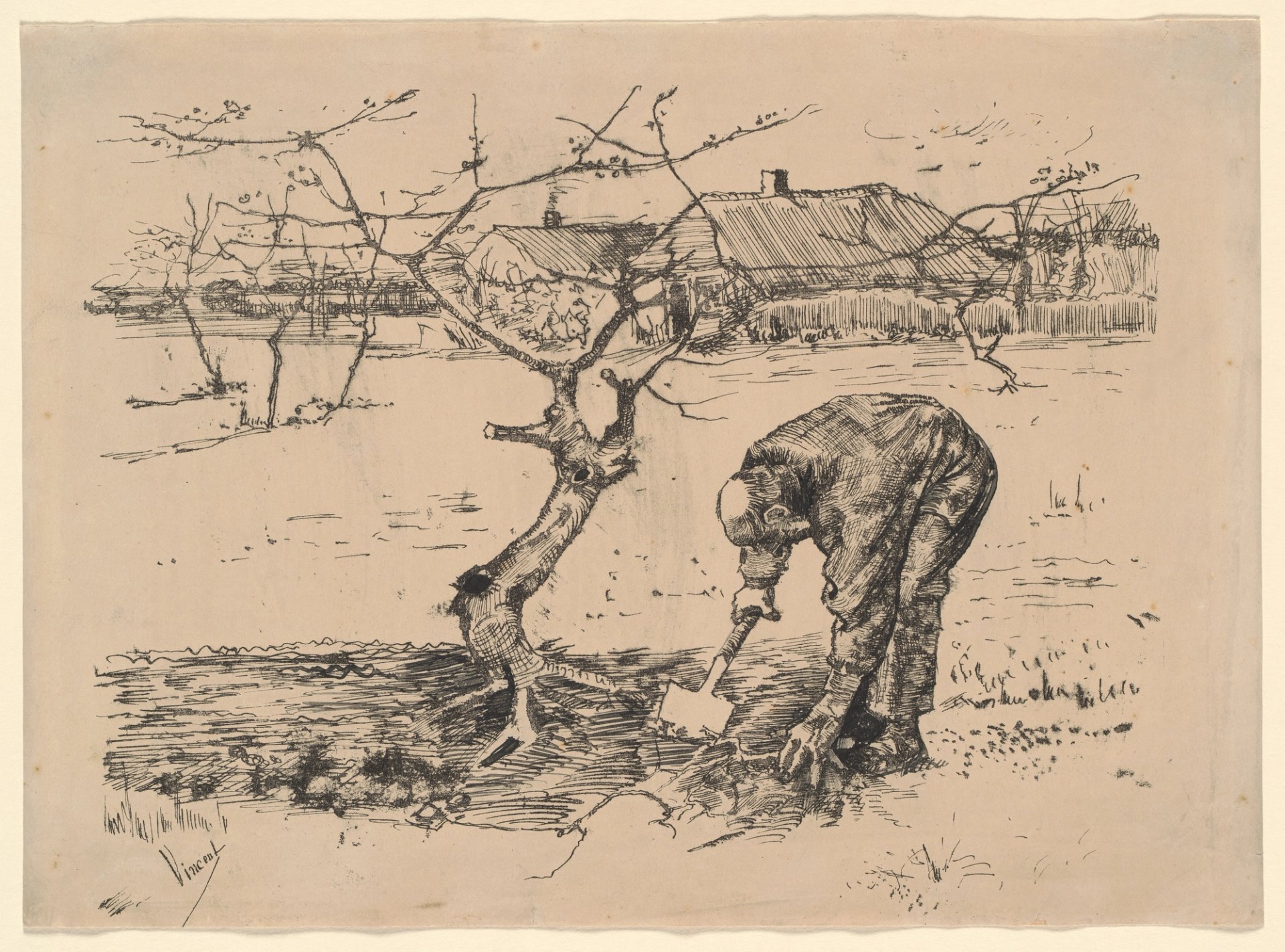

Van Gogh’s Gardener by an Apple Tree (July 1883) Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gardener by an Apple Tree (July 1883), was based on a drawing that he made in the grounds of an almshouse in The Hague. Vincent again included a preliminary sketch of the image in a letter to Theo. The Met’s print has also been touched up with ink.

Vincent’s sketch Gardener by an Apple Tree in his letter to Theo, around 13 July 1883 Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Van Gogh gave the copy of the lithograph that has ended up at the Met to another artist friend, Anton van Rappard. Like the Met’s At Eternity’s Gate, this example was eventually owned by the Lausanne-based American businessman Samuel Josefowitz in the 1990s.

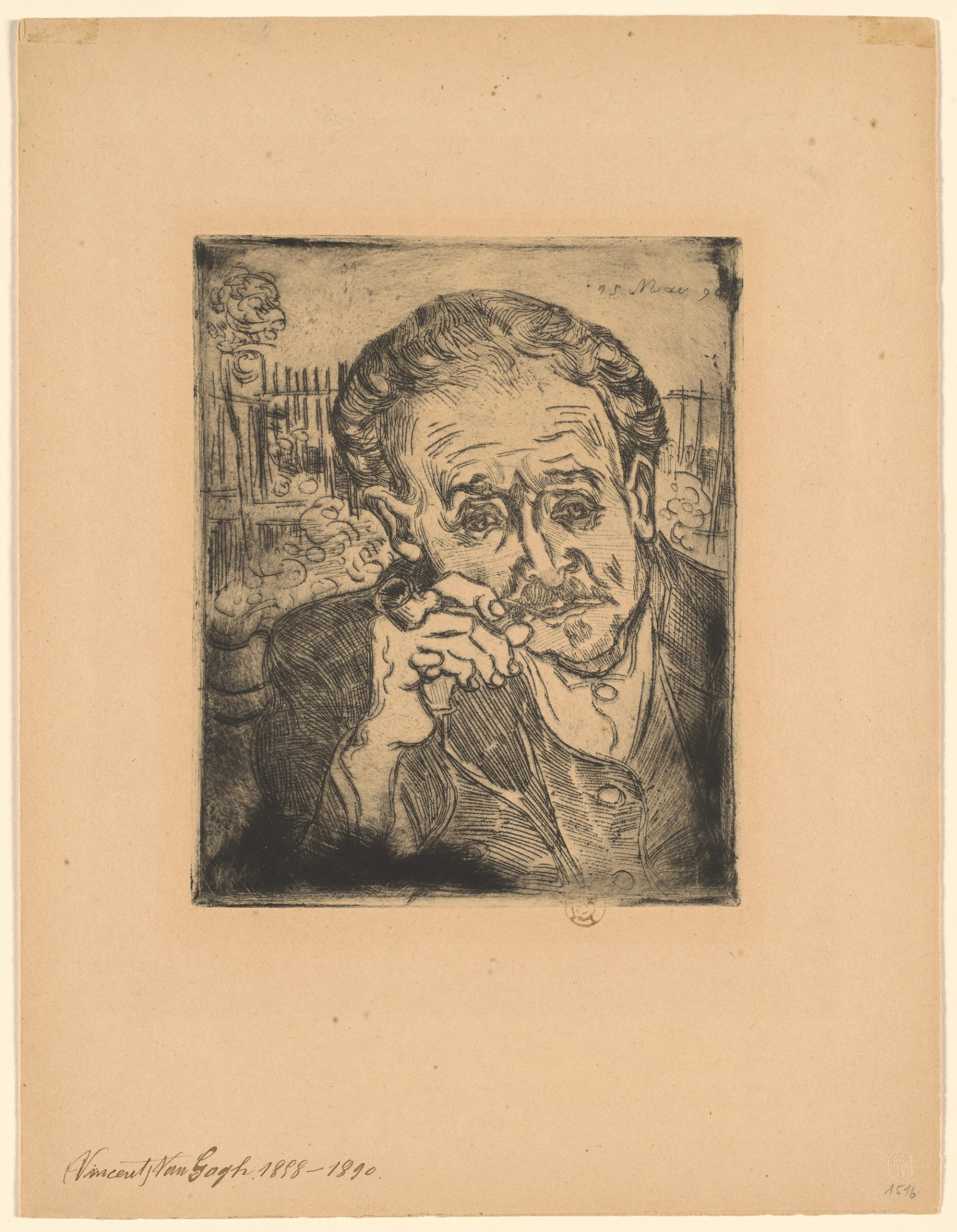

Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet (June 1890) Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The etched Portrait of Dr Gachet (June 1890) depicts the doctor who kept an eye on Van Gogh in the last weeks of his life, in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, just north of Paris. Vincent also made a masterful painted Portrait of Dr Gachet, which has disappeared into a mysterious private collection. It was Dr Gachet who cared for Van Gogh after he had shot himself until his death two days later.

Dr Gachet’s son later recalled how Van Gogh made the etching: “After an outdoor lunch in the courtyard, once the men’s pipes were lit, Vincent was handed an etching needle and a varnished copper; he enthusiastically took his new friend as the subject.”

Although Van Gogh had never previously etched, under the doctor’s guidance in less than half an hour he had completed a portrait of his host smoking in the garden. The two men then rushed upstairs to Gachet’s studio, where they printed some copies. Dr Gachet inscribed the artist’s name in ink in the lower left on the Met’s example.

The etching is much more common than the lithographs, with around 70 impressions known. Last autumn two examples sold at auction, fetching SF330,000 ($362,000) with buyer’s premium at Kornfeld, Bern and $161,000 at Swann, New York (prices vary considerably depending on the impression).

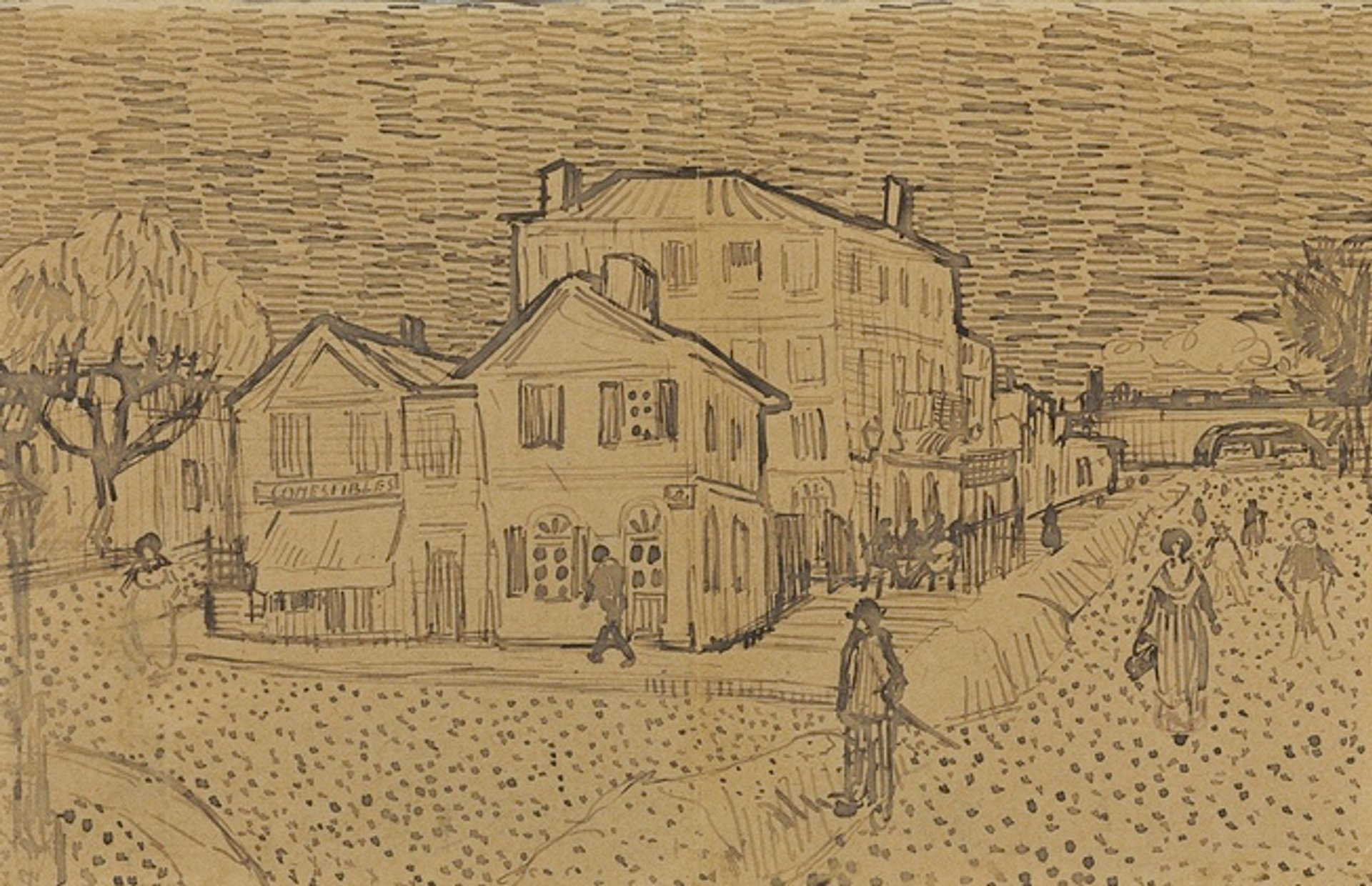

Van Gogh’s sketch of The Yellow House in his letter to Theo, about 29 September 1888 Credit: Image from Vincent van Gogh: The Letters (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam)

As for the anonymous seller to the Met, they might also have been the fortunate owner of an important letter sketch of The Yellow House (September 1888). This was acquired by an unnamed Minnesota buyer at Christie's in 2003 for £845,000 (they sold it a decade later, again at Christies, for $5.5m). All four of the Met’s prints had been acquired by an anonymous Minnesota buyer in 1999-2004, so the seller could well also have been the owner of The Yellow House, although this remains speculation.

When Vincent set out in 1882 to create his first lithographs he did so with the intention of making his art accessible to ordinary people. He wrote to his brother Theo that his idea was to draw working men “from the people for the people”. Vincent decided that “the price of the prints is not to exceed 10 or at the most 15 cents”.

There is no evidence that Vincent actually succeeded in selling any of his prints, but had he done so then the set of four acquired by the Met would have earned him less than one dollar. Although the price paid by the Met is not being disclosed, their prints are now worth several million dollars.