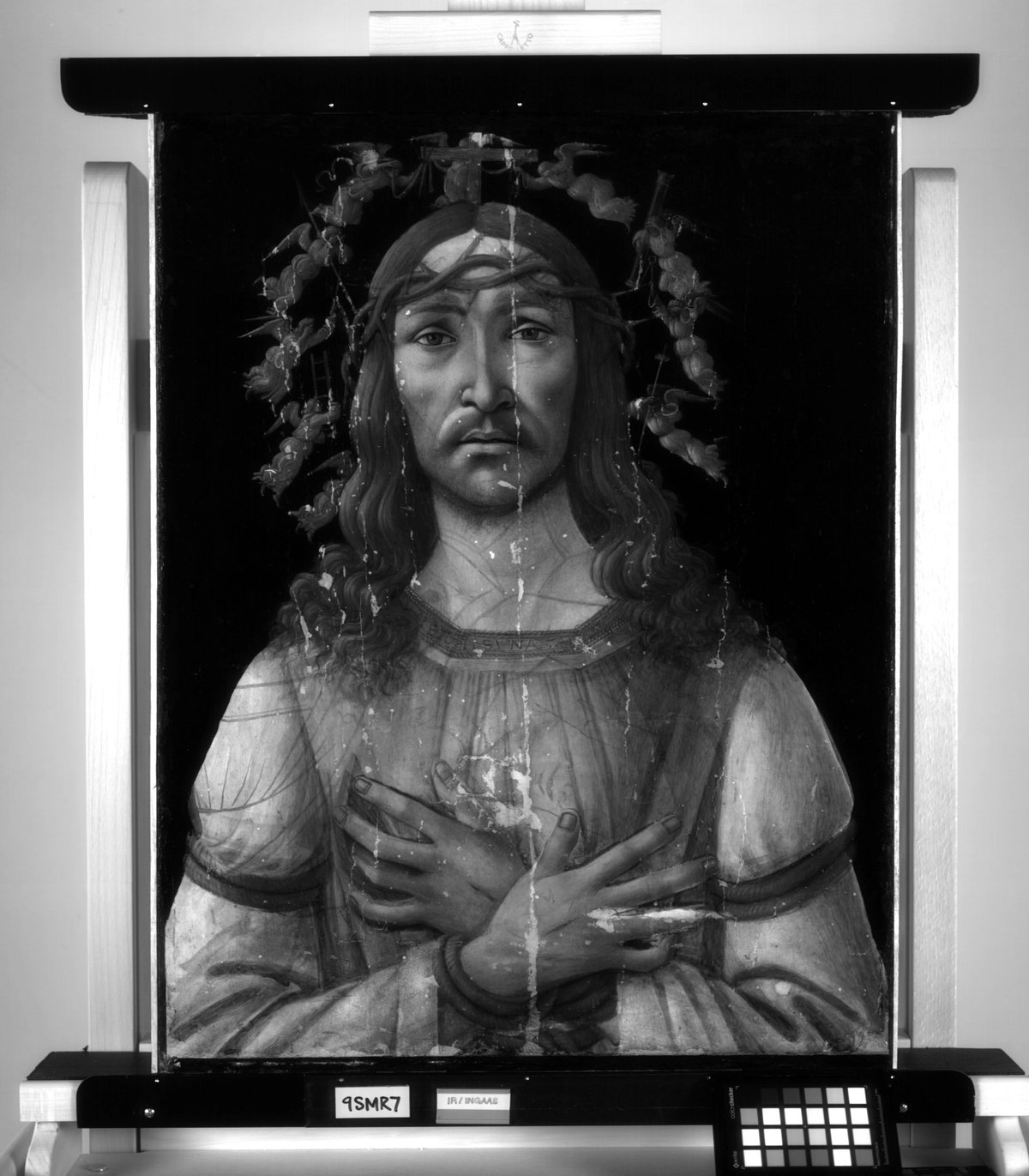

Botticelli’s rediscovered and arresting Man of Sorrows, due to be auctioned at Sotheby’s on 27 January—with a guarantee of $40m—has yet to be studied extensively (it has been in private hands since the 19th century).

But technical analysis undertaken by the auction house in preparation for the sale has already revealed one unexpected discovery: an intriguing image of a Madonna and Child, buried beneath the paint layers.

Chris Apostle, the senior vice president and director of Old Master paintings at Sotheby’s in New York, who has had the opportunity to ponder the picture in depth, believes it to be an abandoned composition of a "Madonna of tenderness" (a type derived from Greek icons), in which the Madonna intimately cradles the head of the baby Christ against her own, cheek to cheek. The facial features, particularly the nose, eyes and laughing mouth, which he identifies as belonging to the Christ Child, are very visible in the infrared image, if you rotate the picture upside down.

The face of a Christ child (rotated upright for clarity) is visible in the infrared image

Courtesy of Sotheby's

This head occupies a space beneath the Man of Sorrows’ chest, while what appears to be an eye and an eyebrow, belonging to a female head, peep out from the area near Christ’s proper right hand. There is also evidence of some white underpainting, possibly in cadmium, in the lower part of the figure. Other visible parts of the abandoned composition include what looks like folds of a mantle, with decorative banding around the shoulder and part of a sleeve, and the Child’s chubby arm is discernible as well.

The red outline on an upside down image of the painting shows the Madonna and Child underneath

Courtesy of Sotheby's

Some lines in this under-drawing are thicker than others, suggesting that they may have been traced from a standard cartoon, and then gone over in a liquid pigment. But the head of the Christ Child, Apostle suggests, is a “one off”: there is no replica in any autograph Botticelli or studio works for what we see here.

So, is it unusual to find such an under-drawing? Apostle says that he has come across this type of thing before. “Panel was a valuable commodity in the Renaissance”, and so if there happened to be an aborted picture just lying around, in this case a Madonna and Child composition (of the type that Botticelli and his busy studio regularly churned out), “then one wouldn’t want to throw it away”. And so, it seems, Botticelli took the panel, turned it the other way, and decided to use it for an extraordinary composition, one which reflects the demi-millennial religious angst of Italy at this time: the work is tentatively dated around 1500, when predictions of the apocalypse and hopes for personal salvation had reached a particular level of intensity.

A type of Greek icon known as a Madonna of Tenderness—this example was painted by Angelos Akotantos in 1420

Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons

The poplar panel that Botticelli used was the standard painting support in Renaissance Florence. Sotheby’s technical analysis reveals a fissure down the middle and an old knot in the wood and shows that the panel was “reconfigured at some point in the 20th century”. Apostle says: it is sandwiched on a modern board, with the original back and front either side of it (“a type of marouflage”, explains Apostle). The paint layers are in “pretty good condition”, a little chewed up at the edges and there are additions to the top and bottom of the picture.

The infrared images also show that Botticelli made certain adjustments to the composition. For example, the tip of one finger that probed the gaping wound in Christ’s side is now covered by his robe and there is a shift in the position of the wound and the profile of the thumb, with the resulting effect that the wound is “down-played” a bit. There is also evidence of longer tendrils of hair, and the outline of a different thorn (emanating from the crown of thorns – above Christ’s proper right eye.). Other changes include the eyebrows being moved down, and a little shift to Christ’s curled little finger. There may be a slight shift to the chin, too, with its discreet, closely cropped beard.

In terms of Botticelli’s typical pictorial technique, Apostle says “he has switched it up” here, blending tempera and oil. “It’s very hard without doing samples to say what the binding medium is”, he adds, “but the technique seems pretty consistent with what I’d expect to see. We have XRF technology so we can look at, for instance, the cadmium element, and we have a lead map, which shows where the fills and losses are. The pigments include chromium, titanium and so on—all the pigments one would expect to see.”

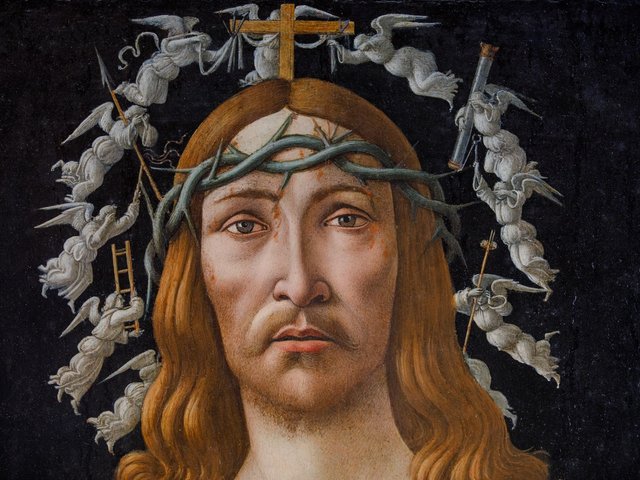

Botticelli's The Man of Sorrows Courtesy of Sotheby's

As with Botticelli’s Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel, sold last year by Sotheby’s in New York for $92m, lead white paint is used copiously throughout the composition, with some mixed into the gesso preparatory ground.

The tiny cross at the top of the composition, has been rendered by scoring lines into the paint surface and then been shifted along (such incisions are also visible in Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel). “It would have been way too far to the right”, says Apostle, though the cross and Christ are still positioned asymmetrically. This asymmetry contrasts with a comparative contemporary image, Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi (another anomalous Old Master image, which famously sold for $450m at Christie’s New York in 2017), where Christ is presented rigidly straight-on, as in the famous "veil of Veronica" image of Christ.

“To me what I find touching,” Apostle says, “is that Christ is a little bit off centre. Botticelli has tilted his head slightly, which is more human. Botticelli would have been 55-plus when this was painted, which in the Renaissance was late middle age, and I feel that there is something about this picture that Botticelli is projecting, an understanding that we are all going to die—it has a profound emotional charge. If he had represented Christ full on and rigid this would be more like an icon; a little bit more impenetrable.”