In 2019, employees at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles elected to form a union, which the institution’s management then voluntarily recognised, avoiding much of the typically combative campaigning that comes with such efforts. Despite this early victory for organisers, contract negotiations between the union and museum officials have dragged. On December 6th, two years to the day after management announced it would recognise the union and after months of waiting, union workers finally got an offer from museum officials in response to their contract proposal, but it was not what they had hoped for.

MOCA leadership rejected union workers’ proposals for higher wages, workplace improvements, better benefits, job security, a greater say in the museum’s decision-making and transparency. MOCA instead proposed raises as low as ¢24 per hour and 1.5% increases in the subsequent year, according to the union’s Instagram page.

According to a spokesperson for MOCA, the two-year negotiation period is typical for a first contract, and the museum administration and union members have reached tentative agreements on issues including sick leave and procedures for grievances and arbitration. The spokesperson also said the museum's most recent counterproposal calls for minimum increases of 7% to worker wages and an average increase of 8.8% in the first year.

Higher wages are one of the biggest concerns for members of the MOCA union, which was formed with the American Federation of State, Federal and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) and represents 78 employees in departments including education, exhibitions, visitor services and engagement, retail and communications.

“I, along with many of my fellow coworkers in the union, felt very disrespected and undervalued by the proposal,” says Anna Marfleet, an exhibitions preparator and member of the organisation committee. “The fact that the museum spent six months stalling and delaying only to deliver a gravely insufficient proposal really shows how little the museum values the time and labour of its employees, and how unaccountable upper management is to the actual workers that make the museum run every day.”

Contract negotiations between MOCA’s union and management began in March of 2020, just as the Covid-19 pandemic took hold. At that time the museum—which has a yearly operating budget of around $20m—laid off all 97 of its part time workers and furloughed many full time employees, decisions that mirrored the cost-cutting steps taken by museums and cultural institutions globally.

In addition to the layoffs and furloughs brought by the pandemic, the period since contract negotiations began has been marked by a number of high-profile departures at MOCA. Most notable was Klaus Biesenbach, who took over as MOCA’s director in 2018 and last September was named as the new director of Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie. His exit came just one week after the appointment of Johanna Burton as MOCA’s first executive director, the result of a splitting of leadership duties that left Biesenbach with the title of artistic director. (Burton has since taken on the role of director, overseeing all operations.)

Three months prior, Bryan Barcena, an assistant curator and manager of publications at MOCA, left for a post at influential Los Angeles gallery Regen Projects. Last April, the museum’s senior curator Mia Locks resigned, writing in a departure email that “MOCA’s leadership is not yet ready to embrace IDEA”, a reference to inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility efforts she oversaw. And last February, the museum’s director of human resources Carlos Viramontes stepped down, writing in a staff email, “I cannot continue to work in a hostile environment.”

In a statement about the current union negotiations, a MOCA spokesperson writes: “We are committed to reaching an equitable agreement. The negotiations are active and ongoing, and we expect that details will be finalised in the weeks ahead. It is our priority to resolve this soon, as MOCA staff are the heart of the museum and deserve a fair wage.”

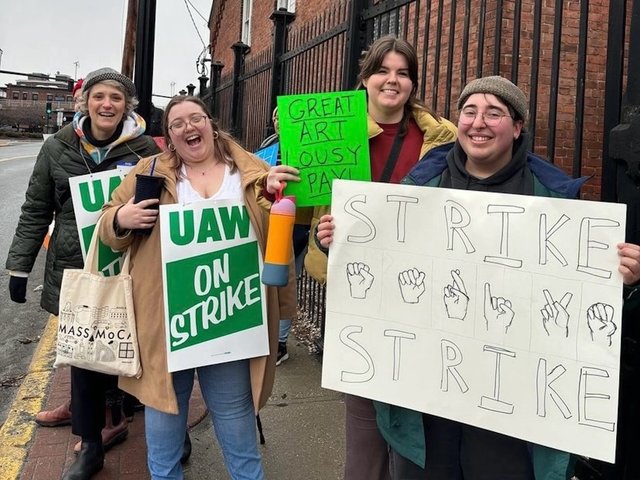

Workers at MOCA are among a growing number of their colleagues at institutions across the US who are adopting a union model. In November, staff at the MFA Boston went on a one-day strike in an effort to help move negotiations with management along.

While contract negotiations at MOCA are ongoing, Marfleet remains optimistic. “The best outcome would be for the museum to [make a tentative agreement based on] our most recent wage counter proposal quickly and without contention,” she says, “and for the union to be able to vote on our first contract before the end of the year.”