Currently installed on a lawn in the middle of Jesus College in Cambridge, England, is a patinated bronze sculpture of two nude figures entwined in a suggestive embrace. One resembles a celestial dancer (devata) typically found carved in ancient Hindu and Buddhist temples, the other a Mannerist portrayal of the goddess Venus.

The work, Promiscuous Intimacies (2020), serves as an introduction to a solo exhibition of paintings, films and mosaics by the New York-based Pakistani artist Shahzia Sikander (until 18 February), which surveys her practice that reinvents Persian and South Asian miniature traditions while disrupting masculine and Eurocentric art historical viewpoints.

“I want the sculpture to make viewers question who's in the position of power here,” says Sikander—"who's holding up who?" Having devised the work after sitting on the Mayor of New York's monument advisory committee, Sikander understands the potent role public art can play within wider cultural debate. "Ultimately I want to interrogate what it means to decolonise. The conversation is so male-centric, and focused around retribution and erasure. Could we conceive of decolonisation as something else? Perhaps reframe it in terms of intimacy?” Sikander asks.

Installation view of Shahzia Sikander: Unbound, Jesus College Cambridge. Courtesy of Vivek Gupta

This question is certainly germane: earlier this year, Jesus College became the first UK institution to restitute a Benin bronze artefact, formally handing over a cockerel statue to Nigerian delegates in a broadcasted ceremony.

The repatriation has coincided with a growing movement in the college to sever ties with one of its most significant benefactors, Tobias Rustat, an investor with the Royal African Company, which shipped more enslaved African people than any other institution during the transatlantic slave trade. Demands to remove a memorial to Rustat in the college’s chapel have been opposed by around 70 alumni, and provide a source of ongoing tension within the institution.

"We don't need to topple sculptures or fight with each other. There are more sensitive ways to go about this complex process," says the exhibition's curator Vivek Gupta, an art historian and academic who teaches at the college.

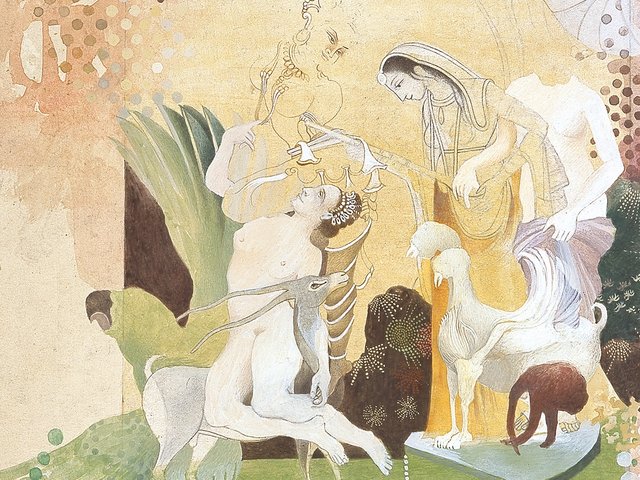

Shahzia Sikander's Khilvat I (2021). Courtesy of Shahzia Sikander and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London

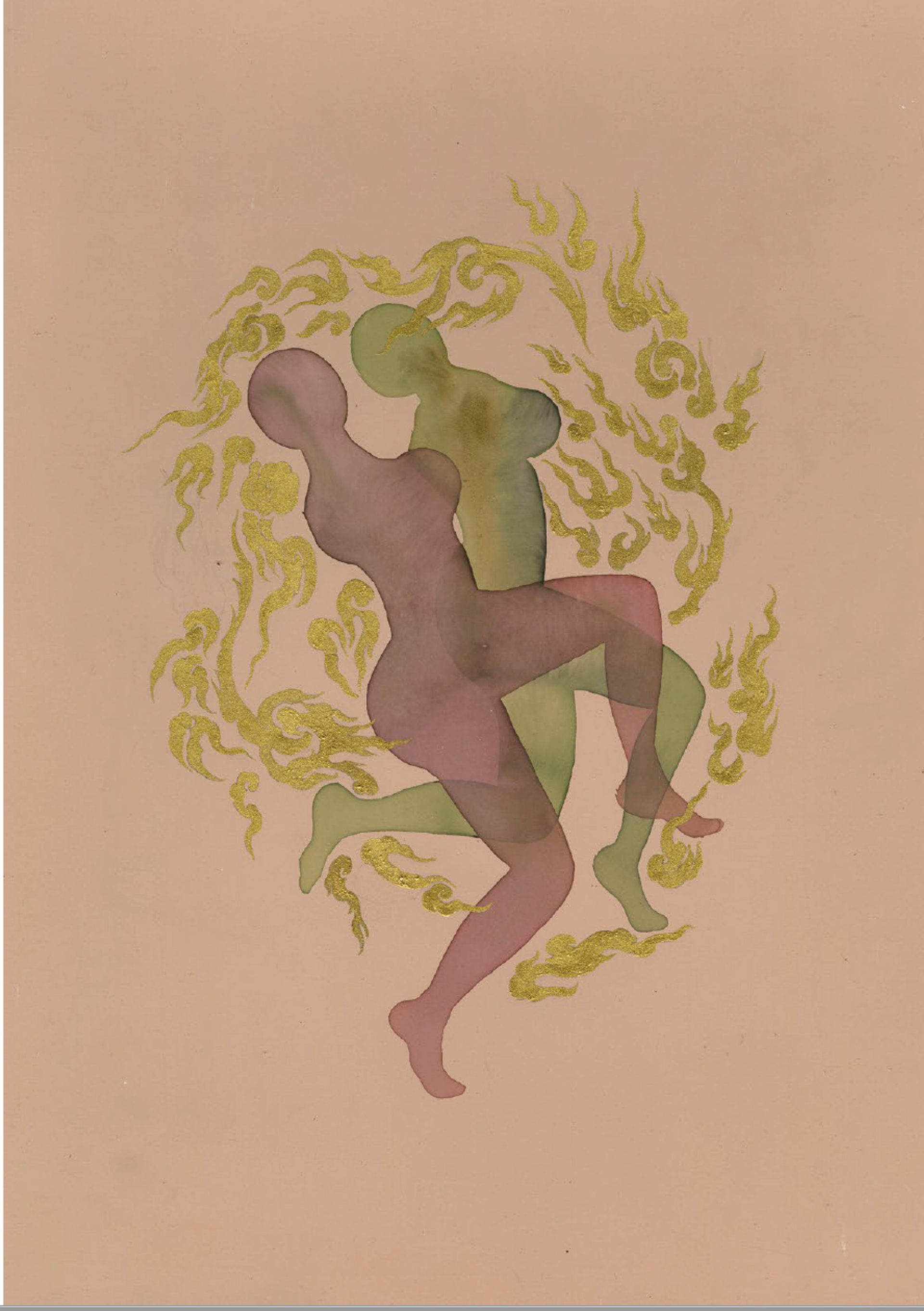

For the show, Gupta, who specialises in Indo-Islamic manuscripts, has brought together a range of Sikander's works that take miniature paintings and manuscripts as their formal starting point. This includes a new series of ink-on-gouache paintings made in response to an 18th-century album of erotic Indian paintings held in Cambridge University's Fitzwilliam Museum, and a 2016 film that animates and deconstructs sections of an illustrated Urdu book of poetry, the Gulshan-i ‘Ishq (1657–58), which is held in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

But while these historic treasures have played a significant role in developing Sikander's visual language since her time at art school in Lahore, her experience of them was largely through xeroxed reproductions until she moved to the West.

"The UK has the best holdings of Indo-Islamic manuscripts in the world, far greater than India and Pakistan. So we also want this show to engage viewers in the conversation around who has the right to own these artefacts, and to draw attention to current attitudes held by many museums," says Gupta. "For example, [the Victoria and Albert Museum's director] Tristram Hunt recently referred to decolonisation as 'impossible and ahistorical'. Are we just going to let him say that? It's shocking."

This topic will be addressed in a symposium at the college organised in connection with the exhibition (11-12 February), which will feature curator and restitution expert Dan Hicks. Central to the discussion will be how our understanding of restitution must extend past the returning of objects.

"Cultural restitution is a much larger process than just handing back a stolen artefact. You have to really deal with the issue and educate communities about decolonisation, which is more difficult and takes more time," Gupta says. "Framing this topic in terms of intimacy encourages you to consider the possibility of a different relationship between a former colonial power and its past subject. It can be a deep and potent way to understand one another."

• Shahzia Sikander: Unbound, Jesus College, Cambridge, until 18 February