One of the most telling paintings done a few weeks after Van Gogh cut off most of his ear is a still life of two smoked herrings. Vincent gave it to his artist friend Paul Signac, explaining that it was an oblique reference to the policemen who had hounded him.

Two Herrings (January 1889), owned privately and only rarely on display, is one of the major loans in the Musée d’Orsay’s exhibition of artworks collected by the Neo-Impressionist, Signac. The important show, Signac Collectionneur, runs in Paris until 13 February 2022.

In March 1889 Signac, then aged 25, set off for the Mediterranean coast to paint. He had got to know Vincent in Paris two years earlier and decided to make an overnight stop in Arles to visit his friend, who was recovering in hospital from the mental attack he had suffered just before Christmas. Vincent had cut off part of his left ear and delivered the morsel of flesh to a young woman in a local brothel.

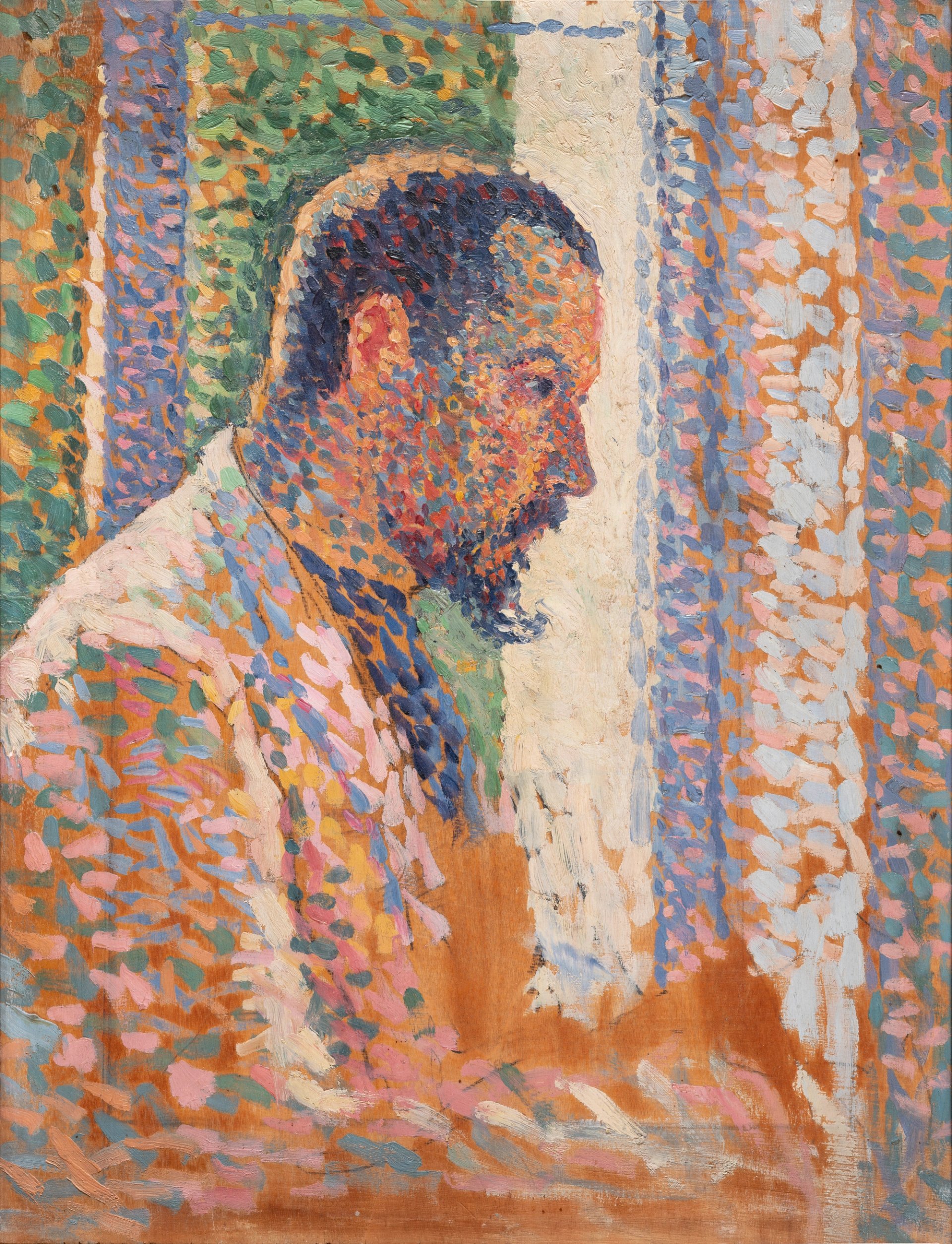

Maximilien Luce’s Portrait of Paul Signac (1889, the year of his visit to Arles) Credit: private collection

Immediately after Signac’s visit, Vincent reported back to his brother Theo: "As a keepsake I gave him a still life which had exasperated the good gendarmes of the town of Arles because it depicted two smoked herrings, which are called gendarmes.” In French, hareng saur (smoked herring, similar to a British kipper) is sometimes used as a slang term for a gendarme (policeman).

Van Gogh had endured several encounters with the gendarmes. Their police station in Arles was located in Place Lamartine, just a few doors down from the Yellow House, the home he was sharing with his friend Paul Gauguin. The gendarmes must therefore have known of these two eccentric artists.

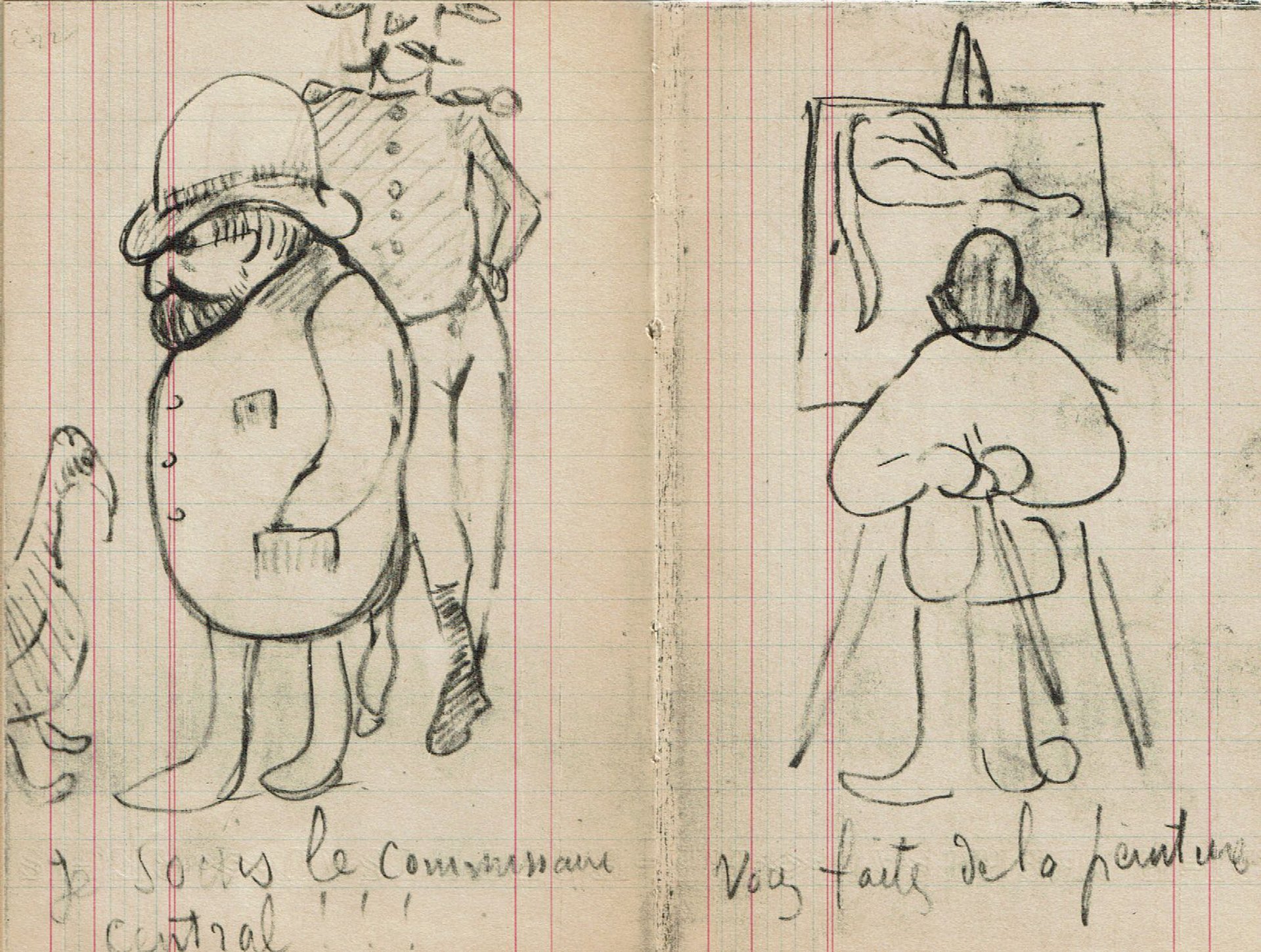

Very early in the morning after Van Gogh had slashed his ear, the police arrived at the Yellow House to determine if a crime had been committed. Gauguin, who had fled from Van Gogh and spent the night in a local hotel, arrived back to find himself questioned by the police. Annoyed by their hostile attitude, Gauguin later drew two caricatures of their chief, Joseph d’Ornano. In the first he appears to be conversing with a goose, in the second he stands bemused by a painting on an easel.

Paul Gauguin’s sketches of the chief of police Joseph d’Ornano—the mocking captions translate as “I am the chief of police!!!” and “You make paintings” Credit: Reproduced in René Huyghe, Le Carnet de Paul Gauguin, Quatre Chemins, Paris, 1952

Although Van Gogh’s physical wound healed relatively quickly, his mental health continued to suffer. Shortly before Signac’s arrival in March 1889, D’Ornano had instructed that Van Gogh ought to stay at the hospital, with the Yellow House locked up.

Signac met his friend at the hospital, with Van Gogh suggesting they should go together to the Yellow House to view his latest paintings. The police initially refused to allow them to enter, although they eventually relented and permitted the two artists to go inside. Vincent had foreseen their obstruction, warning Theo that getting involved with the gendarmes was putting one’s hand “into a wasps’ nest”.

Two Herrings depicts a pair of smoked fish on a crumpled piece of wrapping paper, set on a plate resting on a chair. The pattern of the rush seat provides a textured background for the still life. The same (or a similar) piece of furniture appears in the painting Van Gogh’s Chair (December 1888-January 1889), now at London’s National Gallery.

The perspective of Two Herrings, looking down on the chair, and the complementary yellow and purplish colours would have appealed to Signac. He kept the painting until his death in 1935, passing it on to his daughter Ginette. An inventory taken just after Signac died valued the still life at 30,000 francs, then equivalent to £400 (£30,000 in today’s money).

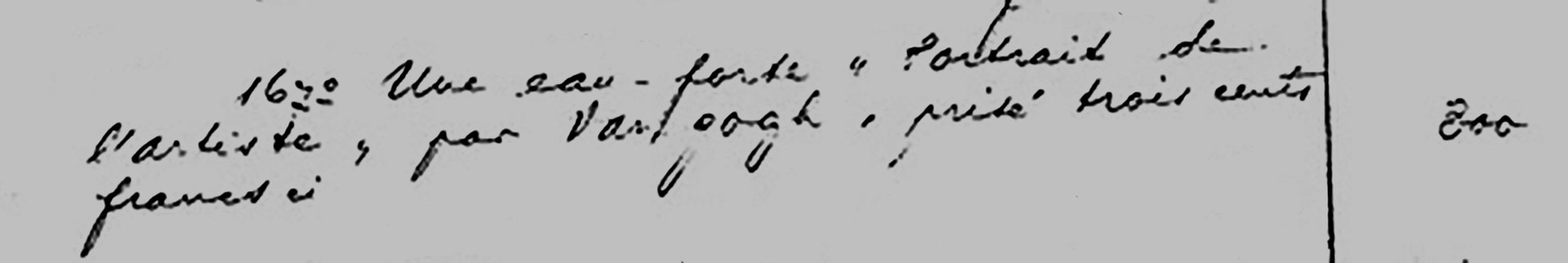

What has escaped attention is a most intriguing second entry in the unpublished inventory of Signac’s artworks which refers to a Van Gogh self-portrait: “une eau-forte, portrait de l’artiste, par Van Gogh” (etching, self-portrait by Van Gogh), valued at 300 francs (£4). Could this really be a previously unknown Van Gogh self-portrait?

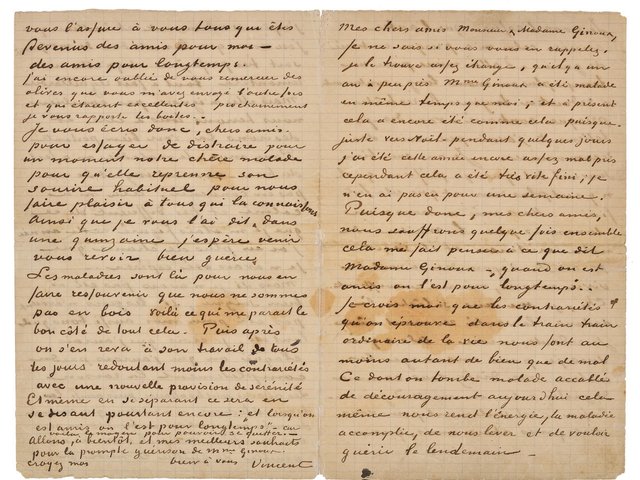

Reference to “Une eau-forte, portrait de l’artiste, par Van Gogh, prix trois cents francs”, inventory of Paul Signac’s artworks, 1935 Credit: Archives Signac, Paris

Disappointingly, the answer is probably not. It is most likely that the print was actually the one etching that Van Gogh is known to have made: a portrait of Dr Paul Gachet (June 1890). Presumably the person compiling the inventory mistook the face of Dr Gachet for that of Van Gogh. Around 70 impressions of the print of Dr Gachet survive, although the inventoried one owned by Signac seems to be untraced.

Signac remained a faithful friend. Just under a year after his visit to Arles a row broke out at the exhibition of the artist group Les Vingt in Brussels. The Belgian artist Henry De Groux, a fellow exhibitor, was horrified by the six paintings that Van Gogh was showing. De Groux threatened to withdraw his own work, “not wishing, as far as I am concerned, to find myself in the same room as the laughable pot of sunflowers by Mr Vincent, or any other agent provocateur”.

At the opening banquet for the show, hostilities broke out when Van Gogh’s supporters spoke out against De Groux, almost precipitating a duel. Octave Maus, the secretary of Les Vingt, later recalled: “[Henri de Toulouse-] Lautrec jumped up, arms in the air, shouting that it was scandalous to slander such an artist. De Groux retorted. Tumult. Seconds were appointed. Signac declared coldly that if Lautrec were killed he would take up the affair himself.” Violence was fortunately averted and the following morning De Groux resigned from Les Vingt.

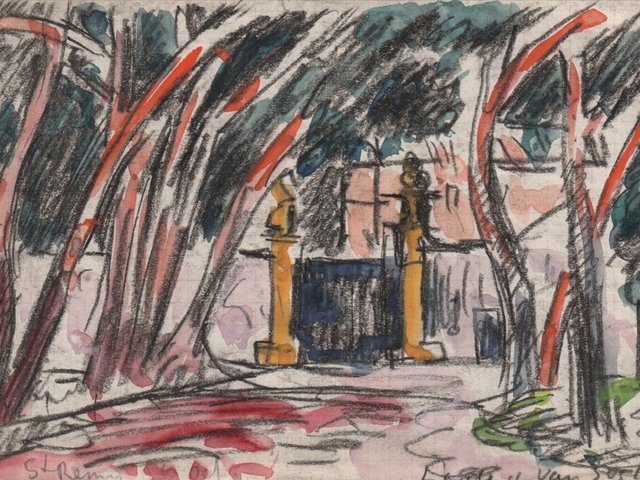

At the age of 69, two years before his death, Signac set off for what was essentially a pilgrimage to the Van Gogh sites in the south of France. He travelled to Arles to see the Yellow House. Signac then went on to the asylum at nearby Saint-Rémy-de-Provence where Van Gogh had retreated for a year.

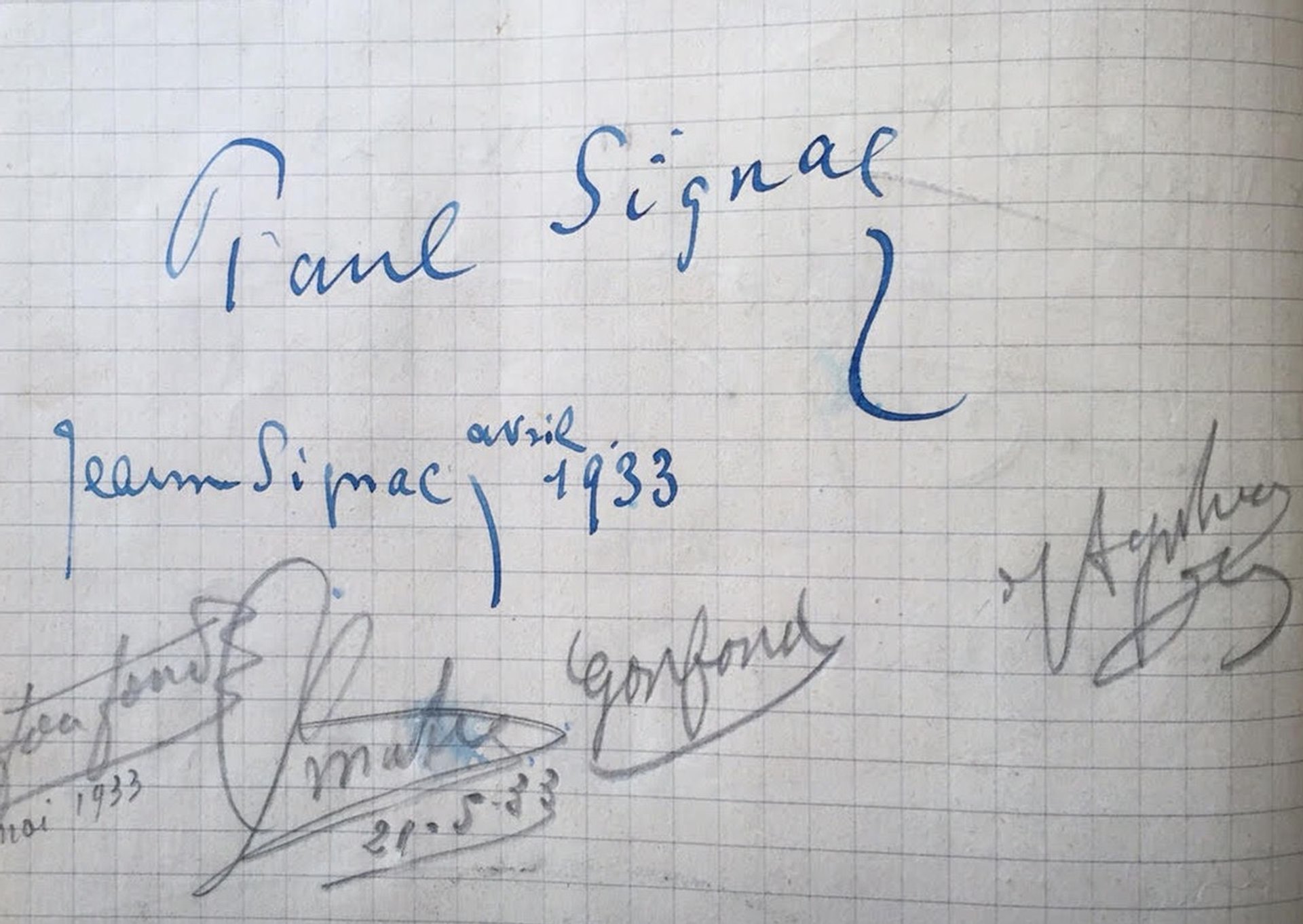

Searching through a newly discovered visitors’ book of the asylum, I found Signac’s signature dated April 1933. As he signed, his thoughts must have gone back to their encounter at the Yellow House, 44 years earlier, and Vincent’s gift of Two Herrings.

Visitors’ book for the small museum at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum, entry signed by Paul Signac and his companion Jeanne, April 1933 © Archives Municipales, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Photo: Martin Bailey, reproduced in Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum, p. 176

Other Van Gogh news

• An early Van Gogh landscape from a private collection has gone on show at the Noordbrabants Museum in Den Bosch in the Netherlands. It now hangs alongside a group of 12 other works from Van Gogh’s Brabant period that are either owned by the museum or on loan. Pollard Birch was painted in the village of Nuenen, in the south of the Netherlands, in the autumn of 1885. The picture belongs to Van Lanschot Kempen, a banking and financial services company based in Den Bosch, and it is on short-term loan to the museum.

Van Gogh’s Pollard Birch (autumn 1885) Credit: Kunstcollectie Van Lanschot Kempen, Den Bosch