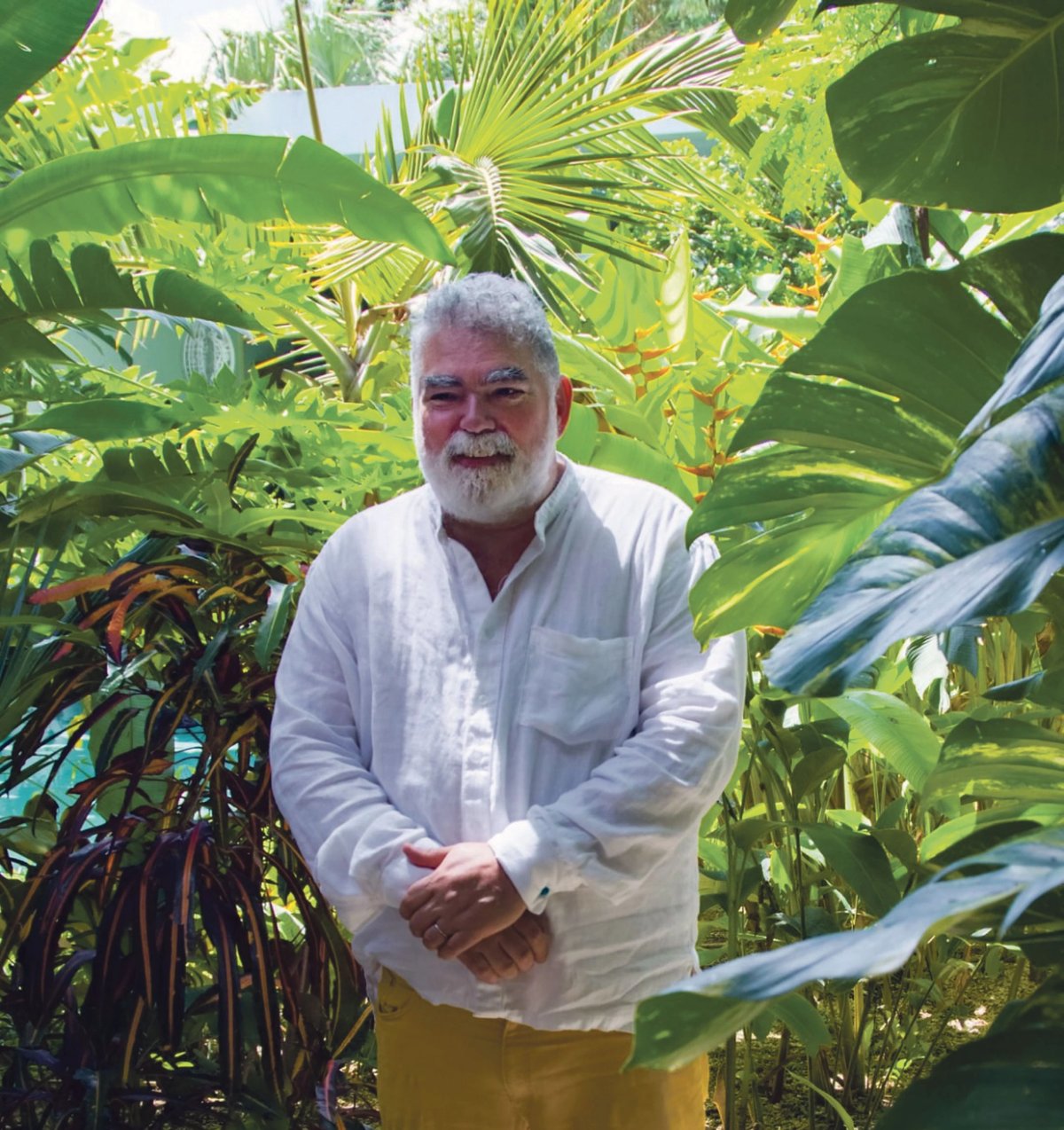

The Cuban American artist Jorge Pardo is constantly engaged in dialogue—within his work, and with his surroundings, his past and his influences. These range from his family’s escape to the US after the Castro regime wrestled control of Cuba, to the Abstract Expressionist painters that first grabbed his attention when he began to study art.

But he is far from stuck in the past. His work, which inhabits a space between art, design and architecture, is very much of the present. His techniques are modern to the point that they rely almost completely on technology, but the work itself does not seem futuristic.

His current show, Jorge Pardo: Mongrel, occupies the Skylight Gallery at the Museum of Art and Design at Miami Dade College. Comprised of 25 new drawings, Modernist chairs and exquisitely complex chandeliers, Mongrel pushes visitors to think about how shapes and hues that are steeped in a hidden narrative affect each other.

The Art Newspaper: There is a semblance of natural, almost biological forms in your work. Is this something you think about?

Jorge Pardo: I studied biology when I was a pre-med major at the University of North Chicago, but just barely. I’m much more interested in other parts of biology, genetics and marine biology, things like that. I don’t think that I use biology per se directly in the forms that I make. I think more about irregular forms, like something that would appear in a garden.

These forms, in your drawings and especially in the chandeliers, can be

so intricate. They must be difficult to actualise.

We work a lot in 3D programs and things like that. In the past 20 to 25 years, it’s been much easier to handle the complexity of those forms as software becomes more advanced.

So, it really comes more from maths than anything else. We have a pretty technically advanced studio. We use CNC (computer numerical control) machines, we use lasers, we use a rapid prototyping machine. Everything gets done on the computer. I don’t even draw by hand anymore, unless it is to communicate with people, when it’s “no, no, not like that… like this” and then I draw something simple to illustrate the idea.

The exhibition Jorge Pardo: Mongrel is at the Museum of Art and Design at Miami Dade College until 1 May 2022

Walk me through how a project begins.

I’ll start on the computer, with the only software I know, form.Z, which is particularly for 3D, and then basic stuff, Photoshop, Illustrator and things like that. Then those images go on to other software that basically allow you to take what you’re looking at, what you’ve sort of frozen in space, and feed it as data to a robot so that it can be made in some rational way.

How recently did technology become such an integral part of your process?

I got my first robot in the mid-1990s.

So you are an old mechanical hand at this.

Yes, I always understood the potential for there to be managed complexity in terms of production and the complex geometries. I was always just thrilled by that. And we have fairly sophisticated prototyping potential in the studio. In a way making art is a lot like making prototypes. Nothing gets made that can’t change.

Where is your studio?

It was in Los Angeles and then around ten years ago I moved to Mexico. I love it down there. I’m in New York a lot more now than I was, maybe 20 days out of the month and then ten or 12 days in the studio. That’s sort of my routine. About five years ago or so I started to spend more time on the screen; I started drawing with found images and found paintings. Eventually I developed a kind of image repertoire with which to make new drawings, paintings and washes—all of which get made on the computer. Then they get vectored, and those vectors are scraped by a laser onto a piece of paper, wood or a canvas before being filled in with colour.

Where do you source these found images?

A lot of this work comes from paintings from the 1940s and 50s. When I started to train as an artist I was most interested in Ab Ex stuff, like Motherwell and De Kooning, and then slowly, as I came to be exposed to work after that, my interest grew. There are also images from the archives of Miami’s Freedom Tower, where so many Cubans, me included, were processed, trained on how to acclimate and become a part of this country. I still have an interest in the visuality of those things. But over time I became more interested in how things work structurally and not just visually. I want to make things that I can read into. If post-structuralism was obsessed with the reader and not the author, I’m trying to find a way to be both.